Analysing South Asian history through films

Critical reading of South Asian history has been majorly subjected to individual narratives. Lack of comparative studies have resulted in ignorance for neighbours and a forgotten history of self. Unlike most academic, information-heavy writings that I have come across, South Asian FilmScape: Transregional Encounters offers opportunities for analytical reasoning and provokes the mind to wander. While some chapters offer new information, others offer varied perspectives on known history, and suggest innovative ways of challenging hegemonic paradigms.

Editors and co-founders of the South Asian Regional Media Scholars Network (SARMSNet), Elora Halim Chowdhury and Esha Neogi De, have meticulously designed the book. They have distributed the chapters of their debut publication equally among the tri-nations—India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, intertwining their history and culture even to the ignorant eye. The selected essays compel the reader to look beyond the contents of the book and trigger an urge to explore, from chapters on "Nations and Regional Margin", to "Transregional Crossing" and "Fractured Geographies, South Connectivities".

I could not resist reading Lotte Hoek's argumentative piece, "Cross-Wing Filmmaking: East Pakistani Urdu Films and Their Traces in the Bangladesh Film Archive". Hoek investigates dominant national trends into forgotten archives of film practice. She takes Son of Pakistan, better known as President (1966), as a sample film—said to be the first children's film of Pakistan, the story is based on Rabeya Khatun's novel Dusshahoshik Abhijan. But taking a stance away from a romantic or nationalistic position, Hoek confronts the people in charge directly. Along with archived materials, she notes body gestures and choices of words of her interviewees, Faridur Reza Sagar and Dr Fazlul Alam. She used statements of the Film Archive Librarian, the Film Investigator, an unnamed person she referred as a friend, and Zakir Hossain Raju in regard to her search for the documentation of Urdu films in Bangladesh Film Archive. She infers the failure of this search as a representative of the actively forgotten history of the Urdu films of East Pakistan.

The 'film investigator' (as Hoek states) working in Bangladesh Film Archive blatantly admits that the archive has not been able to add Bangla language magazines from before 1978 (the year of the establishment of the institution). The mention of the years such as 1971,1975, and 1978 signify times in history which have been important in forming the identity of Bangladesh. The oral histories and myth, reminiscences and documents, all sum up the structure of the created identity of Bangladesh.

Digging deeper, I could see myself walk through the shelves of the Film Archive as I read the book. While Hoek tries to pin the language used in the film, the protagonist, played by Faridur Reza Sagar, told Hoek that he couldn't recall anything about the making of the film. I was taken aback because he has mentioned the film in multiple conversations in local media and has written about it. His essay, titled, "Ami President er nayok bolchi", which loosely translates to "I, the hero of President", was published in Kishorsomogro, volume 1, and later added to a memoir, Agragami Swapnik (2016). The memoir was about the director Fazlul Huq. In it, he recalls travelling to Karachi, Lahore, Pindi, Islamabad, Peshawar, and Swat, besides shooting the film in the East. He also shared anecdotes and details of the storyline but there was no mention of the language of the film. Among other writings in the memoir, veteran actress Nasima Khan reminicised her acquaintance with the director. She worked in the Urdu film Azan during 1962 to 1963, which was much later released as Uttoron, another film by the same director. Nasima Khan mentioned Son of Pakistan being an Urdu film, the first one for children made in Pakistan. She refers to the director as a "brave one" from East Pakistan who proved that Bengali directors were capable of making all kinds of movies in any language. She also credited him for paving the path for future directors of Bengal. This was the moment I was bewildered by these contrasting narratives and thereafter, I was only left to wonder if it could unveil any lead on Lotte Hoek's search.

South Asian FilmScape is, therefore, a journey to the centre of the unanswered questions we ask as film students. Some of these questions lead to answers and some push for further research. Either way, this book is helpful beyond the academic realm. Although the book remains unbiased to the territories, my reading interest primarily leaned towards Bangladesh. And so another important chapter to me was "Silencing Films from the Chittagong Hill Tracts: Indigenous Cinema's Challenge to the Imagined Cultural Homogeneity" of Bangladesh" by Glen Hill and Kabita Chakma.

Unlike Lotte Hoek's nonlinear approach, here the writers walk us through the trail of incidents that form the map of Chittagong Hill Tracts and the history of its people—concepts of freedom, dominance, inclusion and exclusion. While Hoek talks about the act of "othering" between the speakers of Urdu and Bangla, Hill and Chakma present the "othering" of non-Bangla speaking minorities by the dominating Bangla speakers and its projection on screen. The two writings form a diptych; a daunting task that many have failed to compile. They also preserve works of the indigenous diasporic community who are helping to promote their culture to a larger audience.

I was, however, surprised to not find mention of the Hill Film Festival in the chapter. The festival has been running in Bangladesh since 2014. One of the key figures of the festival, Audit Dewan, was mentioned as a director but his initiative of the festival was excluded. I believe festival initiatives are a strong media of communication and it is worthwhile to be included in future editions of the book.

This edition ends with a hopeful reading by Elora Halim Chowdhury, where she looks at friendship and healing in contemporary films about the Bangladesh Liberation War.

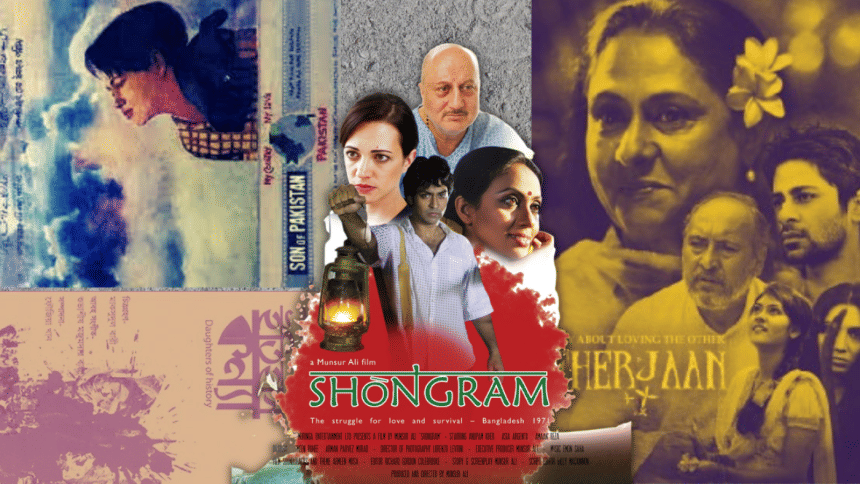

She analyses national films inquiring how it may document and engender a conversation about nation, history, identity, healing and reconciliation. Looking through the lens of both female and male directors, she studies three contemporary films, Shongram 71 (2014) , Itihaash Konna 1, and Meherjaan. She believes that the films chime in to the creation of an alternative archive of 1971 with complex and diverse gender representation and the possibilities of healing and reconciliation through intimate and interpersonal relations.

Priyanka Chowdhury is an art researcher and writer in the making. Email: [email protected].

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments