Are we reading ‘A Seaman’s Wife’ the right way?

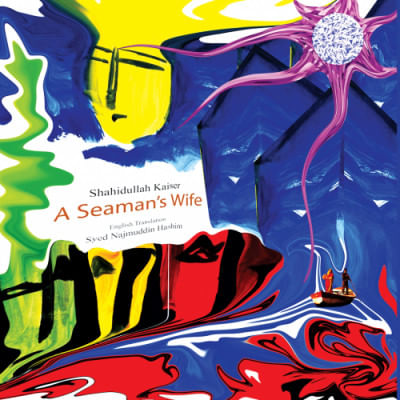

Something that has always fascinated me about Bangladeshi literature is its attachment to and exploration of space. Be it in prose, poetry, or music, almost all our literary work engages with how we are impacted by land, home, country, season, and other natures of charged atmosphere. While revisiting martyred intellectual Shahidullah Kaiser's classic novel Shareng Bou (1962), translated as A Seaman's Wife (Prothoma, 2019) by his friend and eminent author Syed Najmuddin Hashim, the same relationship seemed to propel both the text and my reading of it, this past month.

A Seaman's Wife is famously the story of Nabitun, the wife of a seaman who is waiting for her husband to return from his voyage. In his absence, she has to fend for herself and her daughter without any kind of support that she can accept in good conscience. Syed Najmuddin Hashim's translation succeeds in drawing us into these events, which are all underpinned by Nabitun's, her husband's, and their village's respective interactions with space—space, in this case, meaning land and sea and society.

I say this because nowhere else is the text more vibrant than when it talks about life at sea. "Strange were these men, these sailors," the translator writes. "The roaring, fuming sea and the burling tremendous waves left them only more fearless, more calm. But set them on land and they changed, they were wild."

For Nabitun's husband Kadam and his fellow seamen, love for water, for the freedom and drama and adventure it offers, compels them away from home. The novel poses this in direct tension with that of the seamen's families, whose static lives on land are wrought with uncertainty, insecurity, and festering gossip, particularly for the women who wait and put each other through ceaseless psychological torment. Yet both these parties—the seamen and the "land-locked"—are also drawn to each other. "The land-locked were safely sheltered. They did not know how hungry the ship-bound were for the slightest intimacy, the lightest affection from the people of the land," Kadam ruminates at one point in the text. These complicated, bittersweet dynamics with space are what make A Seaman's Wife truly emblematic of the Bangladeshi experience, and is one of the things that gives the novel its character. The other is anger.

Anger courses through this book from the moment one opens it to find Nabitun warding off lecherous men and the women who pester her about them. As a result, Nabitun is forced to be perpetually irritable, frightened, and even often cruel to her young daughter. This novel as a whole writes its men with more nuance than it does its women, yet it somehow manages to make Nabitun feel like a real person, with real anguish. That makes reading about her life all the more unsettling.

For us readers, this demands some reflection on our part. "A woman is incomparable, because modesty is her embellishment," the narrator troublingly asserts when Nabitun injures an attacker who tries to rape her in a jute field. My copy of the book has the word "No" written thrice in capital letters beside this paragraph. For decades, readers of Shareng Bou have employed this scene to perceive Nabitun as a symbol of "virtuous" resilience—a Penelope waiting for her Odysseus—something the novel's legacy rests upon. That the violence she employs against her attacker can have more to do with self-defense, with her instinctive retaliation against danger, is sidelined. If we are to read this novel anew in its latest translation, the duty to drag these facts to the fore becomes ours.

Reading Shareng Bou as A Seaman's Wife should be about crediting both the author and the translator for penning a story that so realistically sketches the experience of women in rural pockets of South Asia, where their identities and fates are unfairly tied to the actions of their male counterparts, and their worth weighed by their loyalty to and possession by the latter. Reading it should be about noticing the male gaze perpetually trained on Nabitun by the plot, its characters, even its narrator, and it should be about realising that Nabitun isn't worthy of our respect because she is iconically virtuous, but because contrary to her own misgivings, she is as resourceful and self-sufficient as she is vulnerable, humane, and just a woman who misses having her husband at home.

As this new translation opens up the classic to a new generation of readers in English, one hopes that they will read it with a discerning eye and know that to read this novel now is to challenge the systems and social structures which continue to be toxic in the lives of men and women in our subcontinent, 58 years after the book was first published.

Sarah Anjum Bari is editor of Daily Star Books. Email: [email protected]

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments