In ‘Azadi’, Arundhati Roy explores the many layers of freedom

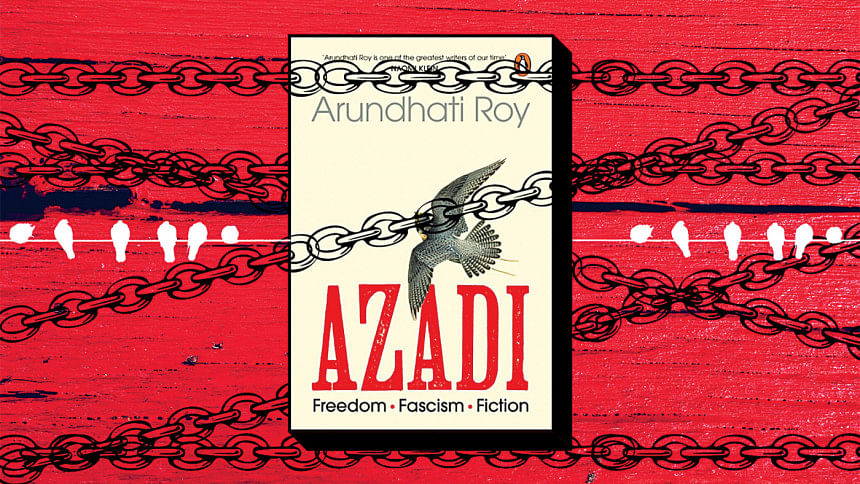

Arundhati Roy's latest, Azadi (Penguin India, 2020), is a collection of nine stand-alone essays, most of which were delivered as lectures or published as columns between 2018 and 2020. Published in early September, the book can be considered a documentation of the ongoing political crises in India, but it also reflects the current socio-political climate of the entire world, in which right-wing ideologies and populism are ever on the rise, and dissent is termed as sedition.

The sections on Indian politics highlight the obliteration of Jammu and Kashmir's special status when articles 370 and 35(A) of the Indian constitution were scrapped, after which Kashmir was driven to a communication lockdown with increased military occupation, and the Modi regime's introduction of the anti-Muslim Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA) triggered protests all over India.

In such a world, where the concept and implications of freedom are evolving on a personal and international scale, Roy traces how "azadi"—the Urdu, originally Persian, word for freedom—found its way from the Iranian Revolution to the Kashmiri struggle for freedom and the feminist movement in the Indian subcontinent, and finally to the thousands of Indians protesting on the streets in favour of equal citizenship. And yet, "the Free Virus has made nonsense of international borders, incarcerated whole populations, and brought the modern world to a halt like nothing else ever could. It forces us to question the values we have built our modern societies on," she writes about the COVID-19, in her introduction. Her intention is to point out that even as religious, cultural and nationalistic differences are sought after to justify segregation, life—through language—often leaks through barriers, staking its claim in the form of slogans, art, and experiences.

And so Roy takes us on her personal journey through language. She describes how India's political reality shaped her writing of The Ministry of Utmost Happiness (2017), in which the characters all come from diverse backgrounds and dialects, representing pluralism against the very idea of "one nation, one religion, one language" propagated by the current Hindu-nationalist regime.

Elsewhere in the book, Roy highlights how the political reality of the subcontinent is interconnected. In the essay, "The Graveyard Talks Back", she writes, "Pakistan, Bangladesh and India are organically connected, socially, culturally, and geographically. Reverse the Hindu nationalists' logic, and imagine how it plays out for the tens of millions of Hindus living in Bangladesh and Pakistan."

In arguing that this common pattern of oppressing minorities was ingrained and strengthened by the blood-stained history of the 1947 partition, she questions whether the narrative of certain Muslims being "Indians by choice" effectively opposes hate-mongering right-wing tendencies, or strengthens the very rhetoric they preach, implying that Muslims have so many homelands, but Hindus have only India. "This plays straight into the binary of the Good Muslim-Bad Muslim, or the Muslim Patriot-Muslim Jihadi, and could inadvertently trap a whole population into having to redeem itself with a lifetime of regular flag-waving and constitution-reading," she writes.

In "Intimations of An Ending", Roy touches upon the NPR-NRC-CAA debate, calling out the current regime boldly for their communal policies and their politics of altering history to spread hate. But she is non-linear in her approach— in "The Language of Literature", she points out that, "The narrative of Kashmir is a jigsaw puzzle whose jagged parts do not fit together. There is no final picture."

In a 2002 speech titled "Come September" (which was later added to her 2019 essay collection My Seditious Heart), Roy admitted to the way in which she talks about power—the paranoia, ruthlessness and physics of it all. In Azadi too, as in her fiction, Arundhati Roy's writing underlines the importance of specificity, of allowing the reader to look down over a particular issue and notice the power dynamics at play. This enables her as an author to get into the complexities and nuances surrounding an issue, with specific names and dates, with bold opinions, so that readers know exactly what she is talking about and where she stands.

Some of the essays in this collection were delivered as lectures and speeches in different parts of the world, as we gather from the footnotes. The variety of locations and platforms indicates how far and wide she has travelled to speak out against political injustices. As a writer and an individual, Roy is wholeheartedly committed to the causes she stands for. Yet her prose is so poetic; it always feels like a conversation, never a monologue. She takes us through the grim realities that we live in, and she ends on a vaguely hopeful note, powered by the conviction, the rage and the pain we must feel within.

Nahaly Nafisa Khan is sub-editor of Toggle, The Daily Star and a contributor of Daily Star Books.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments