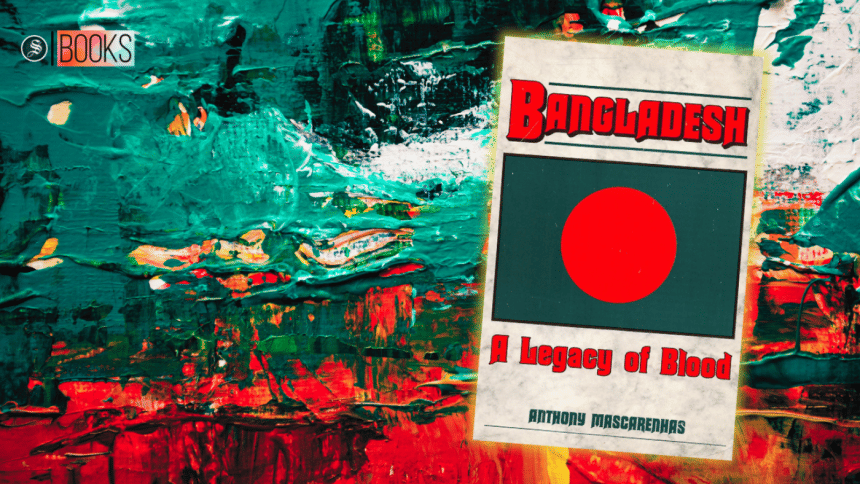

‘Bangladesh: A Legacy of Blood’ is a flawed but essential critique of the founding fathers of our nation

The Liberation War of 1971 and the subsequent dawn of an independent Bangladesh following the darkest nights of Pakistan's onslaught against Bangalis are unquestionably unrivalled as the most romanticised episodes in the collective memory of our nation. However, the days, months, and years that came after our independence are, in the starkest of contrasts, tremendously controversial. In that complex mesh where historical memory and political ideology are inseparably intertwined together and endlessly distort one another, the sets of heroes and villains, saints and devils constantly change depending on who you ask.

In his book, Bangladesh: A Legacy of Blood, Neville Anthony Mascarenhas—the Pakistani journalist who first exposed to the world the brutality of Pakistan's military against the Bangali people—provides his narrative on the realities of post-liberation Bangladesh. In specific focus are the two towering figures of Bangladesh's history and politics, Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman and President Ziaur Rahman—their leadership, and the alleged flaws and contradictions of the two leaders of the nation, each of whom met their end by the assassin's bullet.

Mascarenhas, who enjoyed close relations with Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, having known him since the latter's days as a junior politician under the wing of Hussein Shaheed Suhrawardy, crafts a nuanced portrayal of Bangladesh's founder. Through his own recollections of the candid conversations he had with Mujib, as well as some interviews with those close to him and his adversaries, a complex character is revealed. Mascarenhas says, "Mujib was large-hearted, a kindly man, generous to a fault and who never forgot a face or a friendship." Yet, at the same time, he also describes him as an "earthy, gut-fighting politician" bred in "intrigue and violence". And indeed, this historical account shows Mujib dealing with his opponents decisively and ruthlessly and at the same time patronising his allies to the point of turning a blind eye to their crimes. Yet, he's also alleged to have kept careful tabs on everyone and used the information to suit his political needs.

Mujib is also characterised as being a vain and impressionable person susceptible to flattery. His love for Bangladesh and his desire, determination and doubts regarding developing it all find expression here, and so does his allegedly proprietary attitude towards the country. The writer also provides some examples of him and his family members, much like the other political elite of the time, indulging in luxuries while much of the nation suffered from horrific levels of hunger and poverty.

Another serious, though much more surprising, allegation that the book makes against Sheikh Mujibur Rahman is that he, having been imprisoned in Pakistan for the entire duration of the Liberation War and out of touch with the realities of the newly independent Bangladesh, was considering a proposal by Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto to maintain a link between Pakistan and Bangladesh. After being briefed on the scale of the tragedy and the mood of the Bangalis, he is said to have abandoned that idea.

A Legacy of Blood is highly critical of the way Sheikh Mujibur Rahman handled the country. Here, Mascarenhas describes the lawlessness and corruption that plagued the country during his tenure, the extreme sycophancy and servility of his ministers, and the famine that was exacerbated by the government's ineptitude. The book blames Mujib's centralisation of power in his own hands as what led to people's disenchantment with their leader and hero, and it goes into detail regarding how that, along with Sheikh Mujib's distrust of the army and seemingly discriminatory policies towards it, ultimately set in motion the events of the blood-soaked day of August 15, 1975.

"If he had asked us to eat grass or to dig the earth with our bare hands we would have done it for him. But look how he behaved!" Syed Faruque Rahman, the chief conspirator behind Mujib's killing, had said to Mascarenhas in an interview.

With regard to President Zia, Mascarenhas is perhaps even harsher. To be sure, the book does acknowledge that Bangladesh reached new diplomatic milestones under Zia's stewardship and that he reinforced the Bangladeshi people's national identity, satisfying their emotional hunger. Also mentioned is the strengthening of law and order throughout rural Bangladesh through the making of the Village Defence Force. The transformation and development of Dhaka and other cities during that era is also noted, as is the increasing availability of expensive foreign goods in markets. However, all of these Mascarenhas either downplays or dubs as "cosmetic". The real focus of this portion of his narrative is on the alleged rampant corruption, increasing inequality, and the army mutinies against Zia. He accuses Zia of centralising power into his own hands, much like Mujib before him, and says that he had begun to lose political credibility by the time his presidency was abruptly cut short. He also makes a case that Zia was apparently ineligible to stand in the election in 1978 and presents allegations regarding the election itself being rigged. However, arguably the most controversial allegation he makes here is regarding the character of the man himself.

While Mascarenhas concedes that Zia had lived an extremely honest and frugal life himself, he alleges that he had instituionalised corruption in the country intentionally to fulfill his political ambition of surpassing Sheikh Mujibur Rahman as the messianic leader of Bangladeshis. For such a heavy accusation, however, Mascarenhas doesn't do nearly enough to substantiate it. Unlike with Mujib, he had no personal friendship with Zia from which he could make these deductions about his personality or ambitions. He also does not present any convincing rationalisation on how someone could hope to win the hearts and minds of people through allowing corruption. Instead, he relies on the testimonies of Zia's critics and "some associates" whom he does not name. The effect of this is that his analysis feels unbalanced and incomplete. A more nuanced approach, in the absence of his personal knowledge, would have been to put the opinions of Zia's critics and his loyalists in contrast to one another and let the reader derive his own truths from it. But it is likely that doing so would have exceeded the purpose of this book. In the preface, Mascarenhas admits, "the focus of this book inevitably is on the wrongdoing. I make no apology for it." Therefore, this book, though an essential read for those interested in our history, is still flawed.

Bangladesh today is a deeply polarised nation, and it is a given that such polarisation exists at its fiercest with regard to two of its most popular historic leaders as well. Some hold one to be a visionary and the other to be a dastardly tyrant, while others hold both in esteem as people who contributed immensely to the nation. The narrative Anthony Mascarenhas presents, however, is different in that it casts them both as selfish men whose ambitions brought misery to their people. I believe that if we are to grow as a society and nation, every such historical narrative must be allowed to co-exist, and they all must be challenged, debated, and dissected. It is as Anthony Mascarenhas says, "The people must know the truth about their leaders; and may we all take lesson from their mistakes."

Labib Rahman is a writer based in Dhaka, Bangladesh.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments