Battle cries and sound waves

"Muktishongram-e ami jog diyechhilam bishuddho ekjon biplobi hishebe".

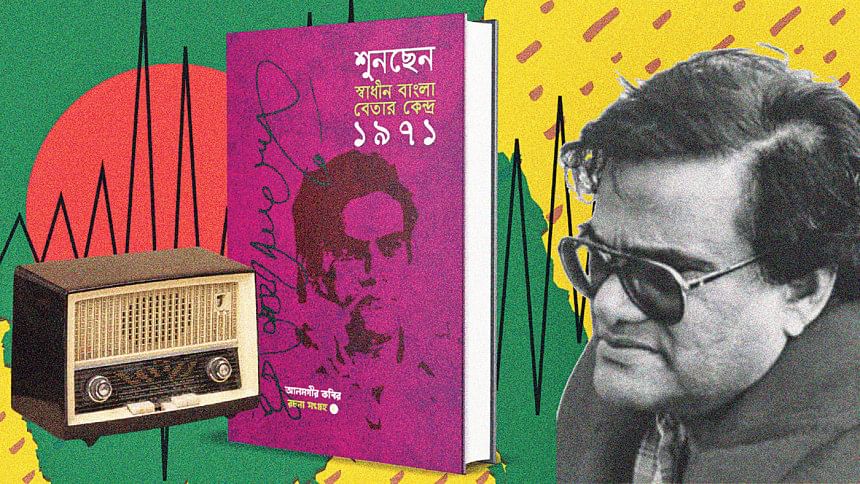

Bangladesh's struggle for independence, which began in full form 50 years ago on this day, comprised a collective fight made up of many smaller, individual battles. Civilians taking up arms without any prior military training was but one of them; others included families battling their fear for life to serve a national project, women trying to fight off sexual and physical violence, and writers, musicians, artists and journalists waging a way through misinformation and low morale to help create and sustain a narrative that would carry people's hopes and fears. The daily radio coverage of the Liberation War between June 15 and November 30, 1971 delivered by Alamgir Kabir, one of the most iconic filmmakers to emerge from Bangladesh's post-war cinema, is an example of this kind of shongram. Published jointly by Modhupok, Agamee Prakashani, and the University of Liberal Arts (ULAB), Shunchhen Swadhin Bangla Betar Kendro 1971 (2020), a newly released Bangla translation of the collection of Kabir's radio dispatches, is an invaluable relic from those six months of the war.

While the struggle continued for nine months, beginning before and continuing after the scope of the book, from the first page Kabir's radio dispatches launch us into the thick of things, with thousands of civilians having lost their lives and foreign newspapers reporting that the horrors of the "Bangladesh tragedy" have exceeded those seen in Vietnam. From here, over the course of 74 episodes presented in this book as separate chapters, Kabir goes on to comment on the geopolitical involvements of other countries including USA, India, China, and Iran, on how Western media was portraying the war, on the narratives Yahya Khan was presenting and the ones he really preferred, on the torture of women and foreigners, and countless other vital episodes of 1971.

Many of these events are well known to us by now, written and rewritten as they are for history books, lectures, and newspaper articles. Such constant rewriting, delivered even with the best of intentions, runs the risk of smoothing over the fragments and ambiguities that offer a true account of history. But while this nostalgia and sentimentalism are essential parts of how we remember our nation's history, books such as Shunchhen Swadhin Bangla Betar Kendro offer the experience of reading about the war as it played out in real time.

On September 25, for instance, we find Kabir discussing the intellectuals and teachers—most of whom seemed to teach in the Bangla department of the university—still being abducted and tortured six months after Operation Searchlight. Poet Syed Shamsul Haq had just been arrested, musician Altaf Mahmud was being presumed dead from torture, and Morning News journalist Shahidul Hoq had disappeared. Thousands of hostages were being held at the Dhaka cantonment, tortured, unclothed, forced to work until they passed out from exhaustion or succumbed to their injuries. "It is clear from these events that the panic that gripped the people of Bangladesh six months ago on March 25 has not ebbed at all", Kabir says in this dispatch. In his September 30 episode, we learn that over 10,000 freedom fighters are ready to join the war.

This isn't to say that this narrative is devoid of subjectivity. On the contrary, Alamgir Kabir's commentary drips with resentment, indignation, and irony every time he talks about Yahya Khan or the hypocrisies of the West. Hope and encouragement wash over his words as he urges his listeners to support the freedom fighters every which way they can. He insists that they take special care of the women and the elderly. And because each episode is kept short and sharp, stretching barely over a page or two in the book, it is easy to remain intrigued and invested, alternately smirking over Kabir's tongue-in-cheek humour and nervously anticipating the outcome of unfolding events. It is apparent that he was trying to motivate and stir emotions in his listeners as much as he was reporting news, even if that required a dose of drama. As we near the few final chapters, titled "Shesh Onko" (The Final Math) or "Aro Ekbar Shoron Kora Jaak" (Let Us Recall One More Time), the prelude to a climax is palpable.

Originally published in English by the Bangla Academy in 1984, This Was Radio Bangladesh 1971 was translated for this project by Afzalur Rahman, Arastu Lenin Khan, Tahmidul Jami, Priyam Pritim Paul, and Shamsuddoza Sajen, but it never reads as if too many writers were at work on the manuscript. If the Bangla feels slightly dense in some places, this is far outweighed by the care with which Kabir's language was adapted into Bangla—words that are more popularly communicated in English were transliterated instead of being translated, and clean formatting and evocative language constantly remind readers that we are reading the radio, not prose.

This book is meant to be savoured—read it in small doses, reflect on each chapter, and take a step back periodically to notice the patterns forming in this narrative of our liberation war. It is as close as we can get to experiencing the tension and excitement of witnessing a nation about to be born.

The print edition of the article incorrectly mentions Modhupok as the sole publisher of the book and Priyom Pritim Khan as one of the translators. The book's co-publishers are Modhupok, Agamee Prakashani, and the University of Liberal Arts (ULAB), and Priyam Pritim Paul is one of the translators.

Sarah Anjum Bari is editor of Daily Star Books. Reach her at [email protected] or @wordsinteal on Instagram and Twitter.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments