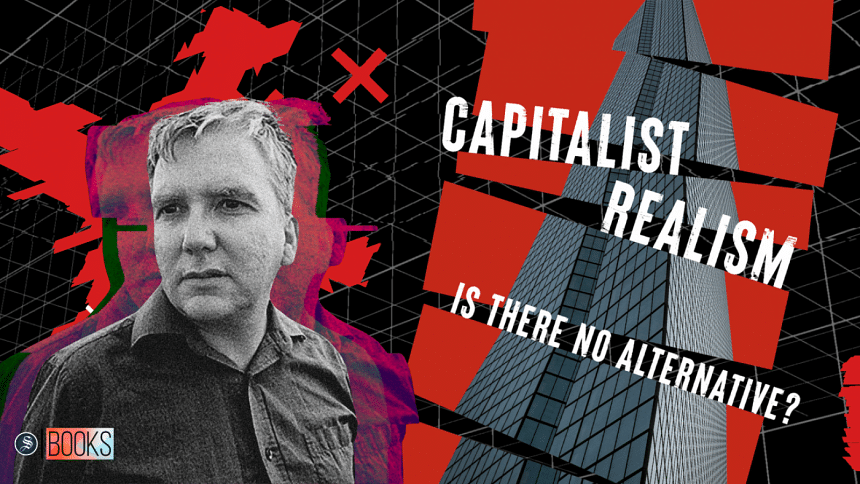

‘Capitalist Realism’: Reading Mark Fisher in a contemporary world

Why does it feel like everything is changing, yet at the same time that fundamentally nothing is being changed? The cultural impasse of watching movies with the same plot device, music with the same tones, and books with the same messages—why does everything seem monotonous? Is it the fabric of reality itself? Or is it someone else who weaves the fabric?

Mark Fisher, in his magnum opus Capitalist Realism: Is There No Alternative? (Zero Books, 2009) tried to answer this question. In a short span of just 88 pages, Fisher analysed cultural malaise through a framework he called " capitalist realism," which, although published years ago, might be relevant now more than ever.

Capitalist Realism can be summarised by the phrase Fisher borrows from Fredrick Jameson and Slavoj Zizek: "It is easier to imagine the end of the world than the end of capitalism." According to the author, the fall of the Soviet Union left neoliberalism without any contenders, and it became an unspoken system. This anonymity is not the weakness of the system; instead, the system derives all its power through not being named—it becomes the air we breathe in but don't notice. As a consequence, individuals under neoliberalism, which grows through the atomisation of society, can't blame anything but the individual causes of societal issues.

Policies regarding the current climate crisis can illustrate this tendency effectively. Policies for reducing climate change frequently invoke individual habits of reducing carbon emissions or tree plantation and blame the individual for not being climate-aware. These suggestions ignore the problem that unlimited capitalist growth in a world with limited resources would only exacerbate climate change. The capitalist mode of production can't survive without plundering the natural resources. A report by The Guardian, which stated in 2017 that only 100 companies account for 71% of global emissions, makes it clear that without solving the neoliberal capitalist model, individual actions are simply not enough. Climate action is a political action, and that is what capitalist realism wants to hide, framing it as not part of the system, but the individual.

Climate action can involve performative activism as well, where the system tries to sell its products through the tag of "eco-friendly". Fisher argues in his book, that this sort of performative activism is pervasive in the cultural sphere, where the most anti-system, anti-corporation art is ultimately a reinforcement of the same system and the same corporate interests. Wearing a Che Guevara shirt may give the consumer a sense of rebellion, but that shirt was manufactured through the exploitation of labour, the very reality that Che Guevara was against.

Capitalist realism can be more intensely felt in the post-pandemic world. During and after the Covid-19 pandemic, the economic issues which left many people in misery (joblessness, scarcity of health products, mass layoffs) were seen as inevitable occurrences, rather than leading people to question the system which made it happen. How did the tech giants acquire more than 1 trillion dollars while the global economy crashed? There is no single answer, but solely blaming it on individual choices is not going to provide the full picture. That is even more precisely avoided through announcing the cultural supremacy of neoliberalism, which claims to have given freedom to the individual, framing their issues as nothing but their own unfortunate choices while hiding corporate interests.

The pandemic further atomised the individual through social distancing and increased online activities, which are, while profitable for tech giants, disastrous for mental health. Fisher uses mental health as an example of ignoring systemic causes, and there is no wonder that he would have connected the current crisis of depression, anxiety, and stress to a system which celebrates hyper-individualism and crude competition, and condemns the collective and the public.

Returning to the first paragraph, why does reality seem so fundamentally unchanging? Fisher argues that the slogan "No Alternative!" is useful for the beneficiaries who, at the end of the day, want to make it seem that nothing else is possible. It makes it seem as if the miseries of human life are the fabric of reality while hiding the fact that it is they who are weaving the fabric.

A sense of despair, anxiety, and nihilism (Fisher talks about another form of escapism: depressive hedonism) pervades the culture, which, in essence, is just the acceptance of the fact that reality is unchangeable—it is the way things have been and will be in the foreseeable future. Fisher's work is far from being too optimistic about it, but a sense of hope can be seen in the last paragraph, inspired by history. While neoliberal politics have been built on the premise of stagnancy, history shows us that no system has been permanent. In the age of nihilism, despair, and frustration, the rebel is only in the opposite: in the hope and courage of thinking new.

Sadman Ahmed Siam is a contributor.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments