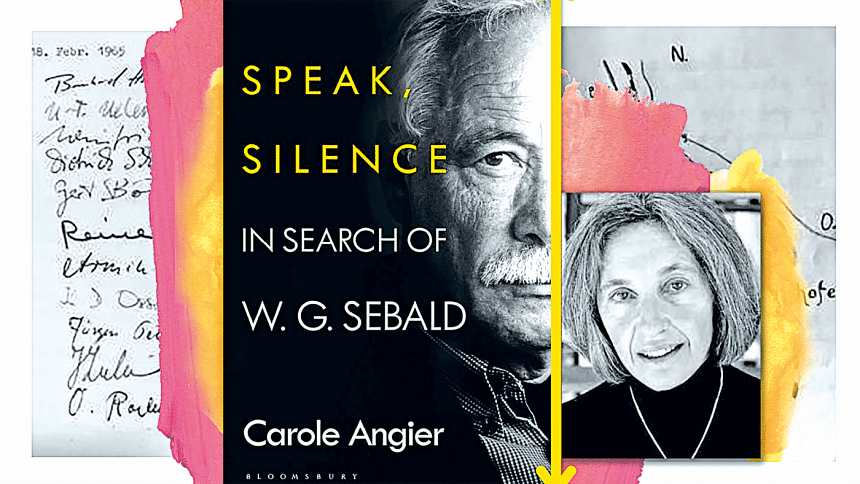

Carole Angier on writing the biography of WG Sebald

Diluting the distinction between documentation and fiction, WG Sebald has introduced a stylistic adjective in his prose fiction, which he refused to be called 'novels'. They are known as being Sebaldian. Carole Angier, an English biographer who laid out the story of the man always in search of memories through fragments of reality and fantasy, spoke with journalist Ananta Yusuf and Shamsuddoza Sajen, Editor of Commercial Supplements at The Daily Star, about Sebald, his life, and his works.

In Speak, Silence: In Search of W.G. Sebald (Bloomsbury, 2021), you write that the author's British publisher, Christopher MacLehose, was in a dilemma to decide on Sebald's genre of writing. After writing about his novel and his life for so long, how would you define Sebald's genre?

Carol Angier (CA): [Sebald] said himself that he just wrote prose, or prose fiction. He rejected the term 'novel' because he disliked the creaking apparatus (as he'd say) of plot and dialogue, of getting people in and out of rooms. He was right to reject the term, and if you expect a normal novel when you open a Sebald book, you'll be disappointed. None follows a normal narrative arc or standard scenes of social interaction. Rather, they take the form of musing and remembering, with long passages of (apparent) digression, all expressed in striking and very beautiful prose. So I would say that they were just prose. And also, certainly, fiction, though they often don't seem to be that. But that's an important question we can perhaps come back to.

How did he achieve this balance between fiction and nonfiction?

CA: The fact that his stories are based on real ones, often closely—is unexceptional; all writers use elements from their own experience and that of people they know. It's the insertion of photographs and documents that makes his characters feel so real. We don't just imagine them as we read, we see them, we look into their eyes.

It wasn't wholly original. Stendhal had used maps and drawings in his Vie de Henri Brulard, for instance, as Sebald shows in the second part of Vertigo. Other French writers like Georges Rodenbach and André Breton had done it, and German ones like Alexander Kluge and Klaus Theleweit, whose work Sebald knew well and admired. But he was the one who made it famous, who turned it into a known genre between fiction and nonfiction that we call, as you've said, Sebaldian, and that many new young writers have followed. Even not so new and young ones, like William Boyd, for instance, in his 2015 novel Sweet Caress.

Do you think the urge for freedom helped Max to develop his own style of writing? And how did he come up with this genre which is hard to define except calling it Sebaldian?

CA: That's a good question! Yes, I'm sure that his need for freedom inspired most things in his life, both good and bad. Most importantly, it led to his critical thinking, and his inability to accept silence and the cover-up about the war and the Holocaust that dominated his early years. That was, to put it mildly, good. But you can't be a maverick in just one part of life; you're either a maverick or not. So for instance, he refused to obey academic rules too—if you rely on some of his footnotes, you'll be in trouble. And indeed he didn't obey literary 'rules' either, though there aren't really any rules in literature.

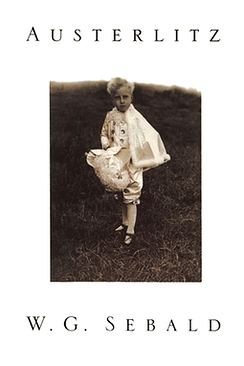

He started his literary writing as the result of a mental crisis that began around the end of the 1970s and beginning of the 1980s. It led him to visit the schizophrenic poet Ernst Herbeck in Vienna, and from there to the journey across northern Italy to the village of his birth in the Bavarian Alps, which he describes in his first prose book, Vertigo. It also led him to the poems he incorporated and developed in After Nature, his first published work, and to a screenplay he wrote even before that, in 1979. In all of them, and in the books he wrote later, culminating in Austerlitz, he explored his own traumas and mental suffering as well as those of his subjects.

In fact he'd been writing since his schooldays, and had determined to be a writer at the age of 20. But this he never admitted; instead he made it sound as though he turned to writing for the first time in his 40s, in order to escape his academic routine.

Despite what I've just said, I think he must have known, at least sometimes and on some level, that it wasn't true. He said it to protect himself and his privacy, which I've invaded in my book. My excuse is that the roots of a great writer's work are of great interest and even importance; and that once someone is dead, they can no longer mind.

"At twelve he had almost been felled by the loss of his grandfather, at fifteen he was writing about death (coffin, coffin, coffin, as Marie says)", you write. Is it his grandfather's death that made him so dark at an early age?

CA: Certainly the death of his grandfather was the first visible trauma of his life. But I don't think it can be seen as any kind of cause. What it shows is that he was vulnerable. So that when later he came to learn about the Holocaust, through his reading and then, shockingly, through a film of the concentration camps that was shown at his school, that was a trauma to him too, more than to many of his better-defended contemporaries. That happened just before he turned 18, and several other things happened at much the same time: he lost his Catholic faith, for example. And at around that time he had his first serious breakdown. He had a second when he came to England at 22: this one precipitated, most likely, by being alone in a strange country for the first time in his life. And then the third, at around 35, that we've already mentioned… He struggled his whole life to remain mentally stable.

Why this was so is beyond my competence as a biographer; we'll know more when his friend Albrecht Rasche, who is a psychoanalyst, finishes the book about him that he's writing. But just because the death of Sebald's grandfather was the first trauma doesn't mean that it was the main or even the only real one, as the scholar Uwe Schütte claims. There is no evidence for this, and much evidence against it , viz. all the other traumas I've listed, and others I haven't. The main one was rather the one he wrote about: the genocide of Jewish people, and other persecuted minorities, by his countrymen. To suggest otherwise is an insult to them and to Sebald himself.

We would like to know more about Max's archive. How did he collect and either include or disregard material in his fictional work? How did he manage this collection?

CA: Stories often began for him, he said, with a photograph. 'Ambros Adelwarth' in The Emigrants, e.g., started from the photo of his great-uncle William that he saw in his American aunt's family album, and Austerlitz from the cover picture of a small boy that he had had for a long time. He often spoke of how photographs moved him, how the people in them seemed to ask to be rescued from oblivion for a moment. That is what he did for them in his writing, and why he included photos in that writing: to give us the same sense of their reality that he had.

He collected a vast amount of material for each of his books: writings, above all; photos, both his own and others'; paintings, maps, newspaper clippings; and other documents, such as the train ticket and pizza bill in Vertigo. All this he put in folders marked with the books' titles. I'm not sure how much of this he did at the time of writing, or whether the final organisation came later, when he prepared his archive, as he did. No doubt a combination of both. At any rate the marked folders of material arrived at the DLA after his death, together with his manuscripts, typescripts, letters and so on. It's a remarkably full and well-organised collection, thanks both to him and to the DLA.

Was he inspired by his favourite writers or he was the one who developed the ideas relating to history and memory from past experience?

CA: He was certainly inspired by his favourite writers, especially by Kafka, Stifter, Robert Walser, Thomas Bernhard. None of these were German, you'll note. Kafka was Czech, Walser Swiss, Stifter and Bernhard Austria. That was typical of Sebald, who came from the edge of Germany, and had, as we know, a great deal of difficulty with his native land. On the other hand he had important heroes and influences among German writers too: Hebel, for instance, and Jean Paul, and among 20th century writers, Alexander Kluge.

They were all hugely important to him and to his writing, as were non-German writers like Rousseau, Conrad, Borges, Thomas Browne. Kafka once said "I am made of literature; I am nothing else and cannot be anything else." We could say the same of Sebald and all his works.

Tell us about the relationship between Max and Susan Sontag. How come you didn't explore the relationship in your work?

CA: Because there wasn't much to tell. Sontag was important to Sebald because she was his most famous early admirer, who made him famous in America, which means in the English-speaking world. She also recommended him to Andrew Wylie, the hugely powerful literary agent, who got him a great deal of money for Austerlitz and several other books. And Max and Sontag did meet a few times: at the launch party for The Emigrants in London, for instance, and at his appearance at the 92nd Street Y in New York. But this was close to the end of his life, and they never became friends.

In fact, Sebald had few writer friends, and no super-famous ones like Sontag. He became well-known as a writer only in the last five years of his life, after he started publishing in English, and he never really moved in the literary world. He wasn't a belonger, and he didn't like being lionised. He just wanted to be left alone to write.

Ananta Yusuf is a journalist at The Daily Star.

Shamsuddoza Sajen is the Editor of Commercial Supplements at The Daily Star.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments