Evil and the divine in Dostoevsky’s ‘The Brothers Karamazov’

My school has a culture—they reward students who top their annual merit list with books. While, for bookworms, this might seem like the most lucrative deal on the planet, I can assure you that most of these books were not the most interesting ones. In fact, I vividly recall my best-friend Tasneem receiving a copy of the 7th season of The Vampire Diaries back in the sixth grade.

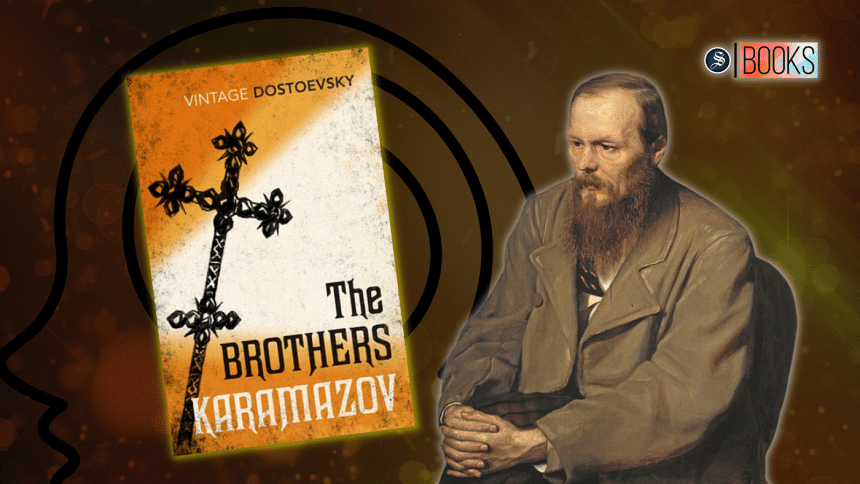

I was one of the luckier ones. I received a copy of Fyodor Dostoevsky's Crime and Punishment (1866).

It was how I was introduced to the literary genius of Dostoevsky, but, for me, Dostoevsky's best work is not Crime and Punishment. Despite being one of the best works ever written, it falls short to his last novel, The Brothers Karamazov (1880). With the plot set in 19th century Russia, the book is a philosophical novel which delves deep into theological themes such as the problem of evil and suffering, free will, and the existence of the divine.

A central aspect of the book is Dostoevsky's juxtaposition of the spirituality of the Orthodox Christian faith—which was deeply embedded within Russian culture and nationalism—alongside the growing influence of atheism, socialism, and nihilism. One of the best examples of this juxtaposition can be found through the characters of Ivan and Alyosha, who are the middle and the youngest of the Karamazov brothers respectively.

In Book V of the novel, titled 'Pro and Contra', the nihilistic and atheistic influence is defended by Ivan, especially in the fourth chapter 'Rebellion' when Ivan meets his brother Alyosha in a restaurant. There Ivan expounds upon and defends his atheistic belief system. He justifies his lack of belief in divine providence by exploring the problem of evil, specifically the suffering of children.

Explaining his stance, Ivan says, "If they [children], too, suffer terribly on earth, it is, of course, for their fathers; they are punished for their fathers who ate the apple—but that is reasoning from another world; for the human heart here on earth it is incomprehensible. It is impossible that a blameless one should suffer for another, and such a blameless one! Marvel at me, Alyosha—I, too, love children terribly." Therefore, a just god if it existed, according to Ivan, would never allow terrible things to happen, especially to a group as vulnerable as children.

Ivan does this to distort his brother Alyosha's beliefs regarding the divine, because he claims he loves Alyosha and does not want him to tread on the path of being a monk.

However, Dostoevsky's true warnings about the nihilistic ideas of Ivan are perfectly illustrated when Ivan hallucinates being visited by the devil. As Ivan seemingly converses with the devil, whom Ivan repeatedly acknowledges is a projection of himself, it seems that his psychological ailments are a result of him collapsing under the weight of his own nihilistic beliefs.

Dostoevsky's stroke of genius is found in his use of the character of the devil to show how in Ivan's version of the ideal world, where a lack of faith is prominent, morality as we know it collapses, and human beings, through developments in science, attempt to rise to the level of the divine. "Man will be exalted with the spirit of divine, titanic pride, and the man-god will appear. Man, his will and his science no longer limited, conquering nature every hour, will thereby every hour experience such lofty delight as will replace for him all his former hopes of heavenly delight." This leads him to conclude that in a world without belief in god, "everything is permitted."

As I finished re-reading the book recently after a four year hiatus, I found parallels between the messages of Dostoevsky and one of my other favorite authors—Friedrich Nietzsche. To me, both shared prophetic warnings about a world where religion stopped existing, but their attempts to deal with the problem seemed different—one seemed to suggest clinging onto religion, while the other developed the philosophy of existentialism to tackle a world without it.

Despite my own lack of belief in divine providence, Dostoevsky's damning portrayal of the vacuum created in a world where ideas such as religion, spirituality and faith take a backseat made me challenge my own ideas about the source of our moral conduct and made me weigh the benefits of lingering onto faith. In a world where we have the growing prevalence of technology and artificial intelligence, Dostoevsky's timeless novel still remains relevant, for it helps us grapple with some of the most important questions concerning mortality, freewill, and existence.

Hrishik Roy is an intern at Daily Star Books and a contributor at SHOUT. Reach out to him at [email protected].

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments