A fellowship of humanity and the wild

The start of Lewa Wildlife Conservancy was rocky. In African countries with colonial pasts, it was all too common for indigenous peoples to view with suspicion conservation projects. After all, they feared these projects—engineered by white people from Europe—were another set of ploys to dispossess them of their land and capitalise on flourishing tourism businesses. After a long spell of persuasion and dialogue between the advocates of the conservancy and the native tribes, the Lewa Wildlife Conservancy sprang up to shelter endangered rhinos. However, the project's success did not only lie in slashing the number of rhino poaching from the Kenyan region. The conservancy created mass employment for the natives, thereby dispelling the doubts they had of neo-colonialism.

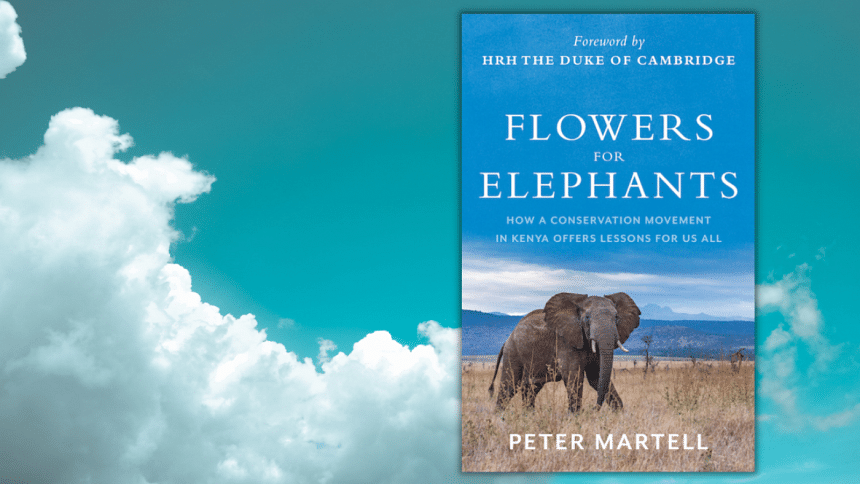

In Flowers for Elephants (Hurst, 2021), Peter Martell uncovers the story of one Ian and Kinyanjui and their efforts to mobilise a conservation movement in the late 20th century Kenya via the establishment of Lewa Wildlife Conservancy. This is not just another story about conservation, though—saviours come from distant lands and lift wild animals out of the mist of violence of a postcolonial country. What sets Martell's angle apart is his focus on how the conservation movement benefited both humans and nonhumans in a symbiotic and ethical manner.

Ian and Kinyanjui's friendship—between a white Kenyan and a black Kenyan—serves as a foreshadowing of things that would follow. Whereas their grandfathers fostered bitterness against one another over land, they were just two simple individuals united by their passion to explore the wild, beyond the shadows of the country's colonial past. Similarly, after the Lewa Wildlife Conservancy began its operations, the warring Borana and Samburu tribes reached the grounds of reconciliation. Previously divided by hatred and violent clashes over land and cattle, now they worked alongside one another as rangers and prevented wildlife poaching.

Lewa functioned on the idea of 'rewilding'. It began as a protected patch of land (Ian's farm) to give shelter to rhinos. The area stretched farther in the coming years and started sheltering elephants as well given how rampant ivory poaching had become. As a result, the wildlife-human conflicts reduced. Moreover, ecological balance was restored. For example, elephants trampled down trees and cleared thick forested areas. Cattle herders were able to graze their cows on those portions of land. After the cattle left, having depleted the grass, the trees grew again and the elephants returned, eating and clearing the vegetation like before. One scientist described the phenomenon as "phantom dancers in a languid ecological minuet".

On the non-wildlife side, having the backing of the UN's Sustainable Development Goals, Lewa facilitated education for the native children, clean water, economic growth, environment degradation, and the reduction of poverty. The "people-focused" approach was a model that benefitted and complemented both: those who loved the wildlife and those who wanted better lives.

The conservancy's success was not limited to itself. It resonated across other regions as new people-centred projects started blossoming such as the Reteti Elephant Sanctuary.

Martell's narrative journalism is a lesson for those in the field as to how a writer can instil empathy for the others around. The reader can taste affection for both the animals and humans in his storytelling. Consider this: He shows that rhinos, too, are intelligent beings. Elvis, an orphaned rhino that had returned to the wild after recovery in Lewa, often peeked into Ian's home as if pulled by nostalgia. As for the humans, Martell provides a concise history of Kenya's tryst with colonialism and how the structures carried over from that period subjugated the indigenous peoples by fanning the smokes of racism. After making the reader contextualise the setting, he puts flesh on the lives of those involved with the conservation movement. Humans and animals, then, jump out of the tents of statistics and newspaper reports.

Photos sprinkle the book at considerable intervals. From Maasai rituals, family compounds, scorched forests, poached elephants languishing under the sun to ranger missions and community meetings, the photos supplement the reading experience by helping to picture what the communities we are reading about look like in their moments of joy and agony.

By illuminating the importance of people-centred environmental projects, Flowers for Elephants offers a loud lesson; environmental policy-making cannot be effective if it precludes the people. Then it becomes just another neo-colonial drive where native human bodies are seen as inferior to those of the wild.

Shah Tazrian Ashrafi is a contributor.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments