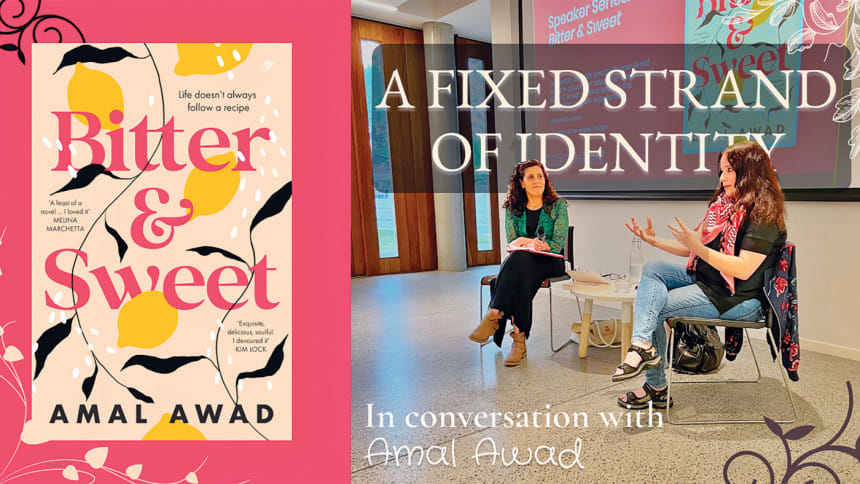

A fixed strand of identity: in conversation with Amal Awad

The sky is overcast as I make my way to Marrickville library in Sydney to hear Amal Awad discuss her current novel, Bitter and Sweet (Pantera Press, 2023). With eight published works to her credit, a red and white checked keffiyeh artfully gracing her neck, Amal Awad is unflinching in her rhetoric about her writing and her identity. So I sat down for an interview with her.

As a Palestinian-Australian, you've stressed the importance of telling stories about everyday Palestinians. Why is it important to tell such stories?

AA: It's essential to normalise people who have been misrepresented across all media for decades. Arabs and Muslims generally have suffered insulting, limiting, and racist treatments, in the world of fiction and in the real one. But I don't feel I need to humanise us. We are very human. My job as a writer is not to convince or teach, or tell people how to think. It's simply to get them to think, and to connect and care about characters they may or may not have known.

One thing I never want to do is over-correct the 'bad Arab' with the 'good Arab', or the 'perfect Arab'. We are humans, we have faults and strengths, we are complex beings and are worthy of being characters existing in worlds that are relatable, without apology.

As recent events in Palestine demonstrate, years of damaging misrepresentation has made it much easier to demonise Palestinians. The role of the artists and writers is to express creatively and truthfully. I don't mean to report on a singular truth, only their truth. And the truth for me is that I don't have a problem with Arabs, the western world and beyond often do. My response to that is not to cater to their demands that I show we're just like them. We exist as we are and it is just important to me to write about Palestinians living normal lives, it is essential. This world, this life, does not belong to one narrative, no matter who dominates.

Do you feel the burden of cultural representation?

AA: I think I did more so when I first started out. My first published pieces had nothing to do with my heritage; they were about everyday things like job rejections and bad grammar and celebrities. Eventually, as diversity started to trend, I did have to mine my own experiences under those identity labels. In some ways, it was relieving to do so. I could own my experiences.

But it was disheartening to see that it was also a very limiting approach. You are not considered valuable or knowledgeable beyond your experience within a minority. I think people wanted writers like me to confirm biases; we are more welcomed when we affirm people's ideas about us, when they can look at us as victims. We're not, but we are knee-capped by existing and long-held power structures.

When con artist Norma Khouri fabricated a life story of oppression and the so-called honour killing of her non-existent best friend, the west snapped her book, Forbidden Love, up. She affirmed the western preference that all Arab women are oppressed, at the mercy of violent men and want to live freely in the west.

You've stated that Palestinians are forced to adopt a 'veneer of politeness' to represent a non-threatening image of themselves. Can you please elaborate?

AA: When I was younger especially, I feel that when someone found out I was Palestinian (something I have always openly shared, and proudly so), they immediately felt they had to share how they see Palestinians, Israelis and the "complicated" conflict. It is uncomfortable for all that is said but also unsaid. And depending on who I was dealing with, there was often tip-toeing around the situation. It was a bit fake and forced, or overwrought in support. I am Palestinian and how I feel about that matters to me more than how other people see me. But you can't say that. You can't say 'thanks for your approval'.

Given the current atrocities being inflicted upon Palestinians, especially in Gaza, I have seen that the pretence, the attempt to mute true feelings one way or another, has dissolved. Many prominent, powerful and often wealthy and well-known people have very openly chosen a 'side'; the deaths on October 7th immediately and unequivocally mattered more to people who are not truly affected by it than the many years of oppression, and many deaths of Palestinians.

In turn, I, and many others, have become activated to be completely open and authentic. We get it – our lives don't matter, our well-being is of no significance. It is shattering and heartbreaking, but also liberating. For example, how many Australian politicians have extended support and care for the Palestinians in the country they are governing?

There is a resurging interest in reading books on Palestine or by Palestinian authors, including yourself, given the current situation in Gaza. What does it signify for Palestinian authors?

AA: Thank you, that is nice to hear. It signifies growth in awareness, but it's tragically under the most vicious of circumstances. But we are here, we exist without need of your approval. Right now, all we seek is humanity, not acceptance.

Books are a portal. Whether they are fiction or nonfiction, stories draw us into potentials and variables. They move us to feel and think, and hopefully in the process, experience some kind of transformation.

Right now, stories by Palestinian writers give depth to the experiences of Palestinians worldwide. We are more than tragedy; we live, love and dream like everyone. I don't want Palestinian fiction to be made exceptional, but it deserves to be celebrated for the way it breaks apart the lies and harmful tropes about us. And it does so in different ways, through a variety of perspectives, experiences and voices.

Your book, Beyond Veiled Cliches, talks about orientalist misconception surrounding Arab women. What prompted its inception?

AA: At the time, I was working in radio, but before that I had written fairly prominently in mainstream media. The Council for Australian-Arab Relations contacted me and suggested I look into funding opportunities if I had any projects that related to Arabs, both abroad and in Australia. It got me thinking and I wanted to do a radio documentary featuring stories and perspectives of Arab women. It didn't pan out, so I decided to pitch it as non-fiction. I had offers from a few publishers. I ultimately chose to work with Meredith Curnow, a publisher at Penguin Random House.

The book was a response to the numerous memoirs written by white women in the west. There was a whole slew of these books, usually involving the word 'veiled' or imagery of that kind. Why were we getting the Arab world from their perspective? I wanted to explore the lives of Arab women by sharing their views and experiences as told to me, both in the Arab world and in the diaspora. It was an offering: if you want to know about us, we can tell you. Not for you. Not to confirm or deny, but simply to share, unapologetically, who we are.

Hollywood depiction of Arabs: cultural appropriation or plain bad taste?

AA: I don't think it's a problem of cultural appropriation, it's just uncomplicated, racist stereotyping. Hollywood tropes are one-size-fits-all. As long as Arabs on screen are written by non-Arabs, they will always be serving the prejudices of the non-Arab. It doesn't matter if they make the Arab 'good'; that in itself suggests how uncomplicated the messaging is. We exist as either an enemy or a non-threat. We can tell much better, deeper, more textured stories. We're just rarely given the opportunity to do so.

Your latest novel, Bitter and Sweet, is an ode to Arabic cuisine. What role does food play in establishing identities?

AA: I don't think it can be overstated how important food is. You might be almost completely 'western', but you likely grew up with your cultural cuisine and this is a fixed strand of identity. It is a link to a place you may or may not know. It gives colour and range to your personhood and cultural experiences.

What is a fond memory of your visits to Palestine?

AA: The hardest things were always getting in and out, and dealing with checkpoints. A highlight, no matter when I visited, was always visiting Jerusalem. It is something very special. I absolutely love Palestine and my relationship to and appreciation of it has progressed with each visit. I have seen so much change but there is something very special about that part of the world. The air, the earth, the history and people. It is so different to life in Australia, so visiting Palestine has always been affecting and transformative. I feel my connection to ancestors and the land they honoured so much more deeply.

Any favourite reads by a Palestinian author?

AA: I frequently revisit the poet Mahmoud Darwish, particularly Unfortunately, It Was Paradise.

Nabilah Khan was born and raised in Bangladesh and currently resides in Sydney, Australia. After more than a decade working in the global banking and financial services industry, she now works in the Australian public service.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments