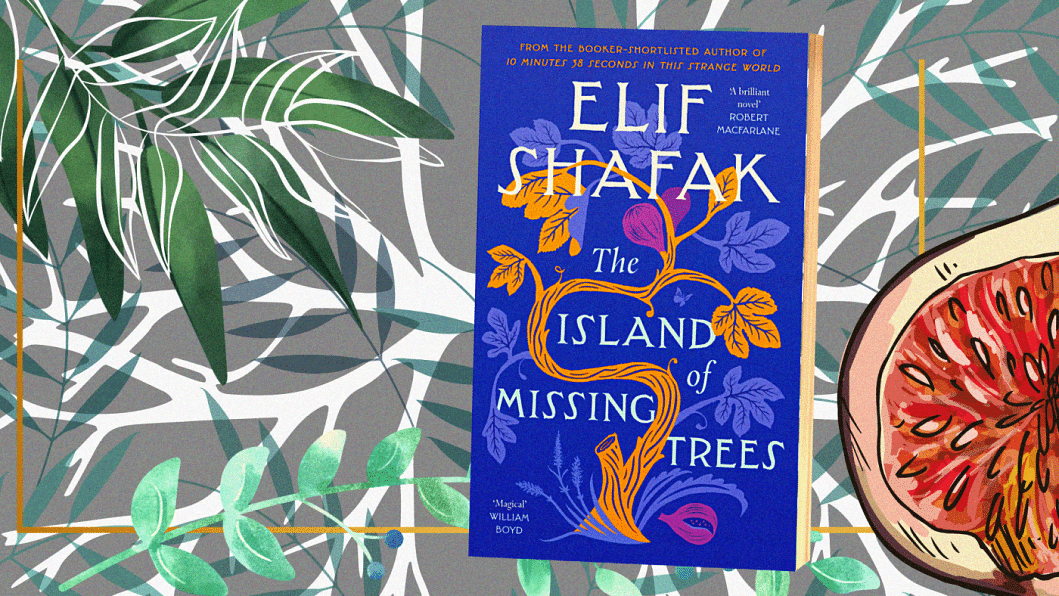

Elif Shafak’s ‘The Island of Missing Trees’: Fragments of an uprooted people

The people we meet in Elif Shafak's The Island of Missing Trees (Viking, 2021) are haunted by terrible tragedies from several years past, by a beautiful island divided into two. To them, their story is broken, spread out over multiple places and decades. Shafak takes us on this journey and, through deft plot devices, helps us piece them together.

The first (human) character we meet is Ada Kazantzakis, a teenager living with her recently widowed father in London. Ada knows little about her parents' past lives, about the island they came from, and the pain they brought with them. When Aunt Meryem, her mother's sister, steps into their lives, Ada, though initially resentful of her aunt's not being in touch, starts asking questions about a past rarely talked about in the family.

Ada's father, Kostas, comes from a Greek Cypriot background, and her mother, Defne, was from a Turkish Cypriot family. When they were growing up in Nicosia, the capital of Cyprus, it was still an undivided city, even though tensions between the Greek and Turkish communities were rapidly on the rise. As a result, theirs was in many ways a Romeo-and-Julietesque love—a forbidden love aided in secret by a few.

The relationship between Kostas and Defne, like their island, like the people around them, was fragmented by conflicts and time. Along with Ada, we start delving deeper into a story filled with interruptions. What happened all those years ago in Cyprus, when neighbours turned on neighbours, when the harmony that had existed on that island for centuries was disrupted, when the place of colourful myths and history was marked by death and violence, when the city her parents always held so close to their hearts was divided?

In the unfolding of this tale, a fig tree plays an important role. As we go back and forth between decades, the tree, an occasional narrator, fills in gaps, as she bore witness and heard things several human characters have not. She gathers fragments from creatures, like ants and bees, that communicate with her, connecting dots in the sprawling narrative. Her life, too, has been an existence of interruptions spread over two countries, like that of Kostas and Defne. Like them, she carries wounds and nostalgia, longing for the island she originally is from.

In her interviews, Elif Shafak talks often about the dangers of ultranationalism, of tribalism, of identity politics. How these dangers fracture places and lives is one of the issues explored in The Island of Missing Trees. We witness small, inspiring acts of resistance throughout the novel. Defne, for example, repeatedly refuses to put labels like 'Turk' or 'Greek' on people. She refers to both the victims and perpetrators, like herself and Kostas, as children of the island who turned on, or suffered at the hands of, each other.

Time and time again we have seen, both in reality and fiction, how generations are shaped by disasters, by wars, no matter how much older generations try to hide their traumas. Memories and secrets persist in unrecognisable forms, ever present in the background.

Years ago, Shafak explored the concepts of generational trauma and the long-lasting effects of old tragedies in her celebrated The Bastard of Istanbul (2006). In her latest novel, she explores these concepts once again, but this time, with a poetic touch so sublime that even I, a devoted admirer of her work, was surprised. In The Island of Missing Trees, Elif Shafak is at her finest.

Shounak Reza is a contributor.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments