Growing up with Narayan Debnath’s ‘Nonte-Phonte’

On a particularly slow day, all I have to do is sit down with a Nonte-Phonte comic book, and my troubles will lay forgotten to one side. I imagine it's the same for most people who are fans of Narayan Debnath and his fictional characters from the small town of Paschimpara, West Bengal.

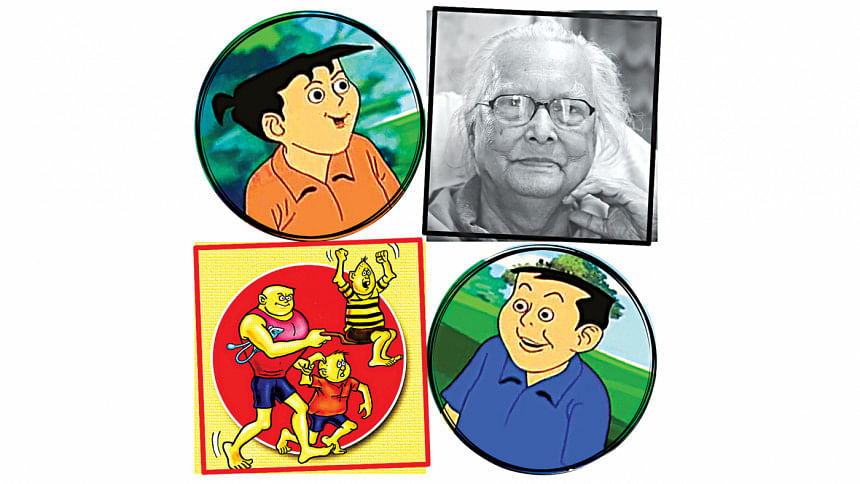

The unique illustrations coupled with quirky and colourful Bangla vocabulary that the author undoubtedly carried over from his childhood in Shibpur, Howrah, all make for a wholesome reading experience every time one picks up a copy of these books. As a fan, I'm eternally grateful that Debnath opted to stray from their family business of gold retailing, after dropping out from the Indian Art College in the 1940s, to pursue freelance work in art and design. While he illustrated plenty of children's books throughout the 1950s, it wasn't until 1962 that he released his first comic strip, "Handa-Bhonda", in Shuktara magazine. The Nonte-Phonte series—and the witty humour with which Debnath weaved together his stories of small-town kids and their proclivity for pranking unsuspecting targets—started out in 1969 as a comic-strip in the Kishore Bharati magazines.

It all went down in an unnamed boarding school for boys in West Bengal, where the eponymous Nonte and Phonte were best friends studying and residing together as juniors alongside their constantly-scheming senior, Keltu Kumar, all under the strict supervision of the boarding's hostel superintendent sir, Patiram Hati. Over time, I even began to regard one of my cousins as the real-life counterpart of the fictional Keltu from the series—such was the comics' influence on my childhood.

Narayan Debnath succeeded in offering me that which no other comic book writer-illustrator could: comfort in my personal identity. As a Bangladeshi with roots in West Bengal, the Nonte-Phonte comics were a source of bibliotherapy for me, providing me with insight into the lives my ancestors had led. The more I read about that small town of West Bengal, the more I began to understand how the inhabitants of said region carried themselves and interacted with each other. Having never visited my ancestral lands myself, the Nonte-Phonte comics helped me draw a parallel with the stories I'd always heard from my grandparents. I eventually came to have a better understanding behind the little things that made up parts of my cultural background, from items of food to slang from a bygone era.

What added to this sense of comfort was that, unlike most children's books that were widely available at the time, the Nonte-Phonte comics didn't come with an obvious set of moral codes for children to follow. Instead of lecturing kids on how to be a kid—which was a rather prevailing tone in the didactic children's books in the 1990s-2000s, such as Winnie the Pooh, Dr Seuss and Beatrix Potter —Debnath truly understood what it meant to be a child. There were no apologies made for playing a prank on an elderly member of the community, or for stealing homemade food from classmates.

There were other books by Debnath that left a mark on my childhood. Handa-Bhonda (Shuktara), a spiritual predecessor to Nonte-Phonte, set in the same universe, and Bantul The Great (Shuktara), which gave Bengalis our own version of Superman in the form of Bantul. As an adult, however, it is with Nonte-Phonte that I relate to the most, picturing myself wandering about the streets of Paschimpara with hostel superintendent sir Patiram Hati in tow, or gorging on the cream cakes and chicken kabiraji from Abar Khabo Restora.

The wordsmith and artist behind this childhood-defining comic books is no more, having breathed his last on January 18, 2022. His legacy will continue to live on through his iconic creations.

Rasha Jameel studies microbiology whilst pursuing her passion for writing. Reach her at [email protected]

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments