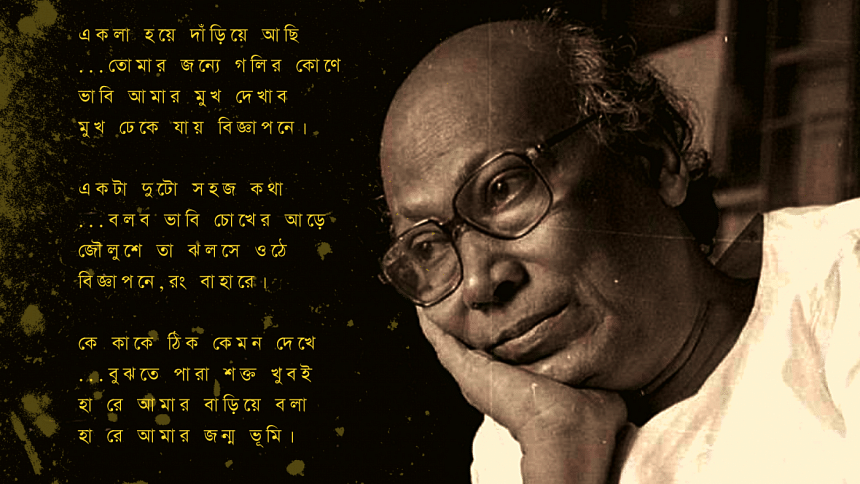

Listening to Shankha at dusk: a requiem for a poet

My late grandmother would immerse herself in the rhapsodic melody of Muhammad Iqbal's poems in Urdu, recite them aloud while taking a stroll around the house and say, "Eta ek alada shaad, banglay er khoj milbe na—this is a different taste, one wouldn't find it in Bangla". A few years later, Shankha Ghosh's masterful translations of Iqbal's poems would appear in the anthology, Iqbal Theke (Papyrus, 2013). My grandmother was so delighted to be proven wrong. This is one atop a long list of reasons why I am indebted to Ghosh—for the sweetest memory of my grandma.

This collection not only bore testimony to his finesse as a poet and translator, but the annotations and critical notes peppered throughout the collection also dissolved the barrier between the text and its critical appraisal in an effortless fluidity. Ghosh, whom the world lost to the coronavirus on April 21, 2021, has left a mark of his impeccable analytical prowess in his attempt to draw parallels between Tagore and Iqbal, an ambitious attempt that he succeeds at elegantly. What in any other hands would have been a mere translation of verses, becomes under the influence of Shankha Ghosh an union of not only two titans of world literature, but also of two literary traditions and of two great languages. It is hard to think of another literary endeavour that is comparable to it in scope and rubric.

Ghosh's translations have undoubtedly enriched Bangla literature, but what is most fascinating to me, personally, is his ability to show his readers the inherent potential in language itself. His poems usually utilise an unassuming diction devoid of any verbosity. The clarity of his voice hits the reader like a roll of thunder. His defiance for establishments—literary, cultural, or of the state—marked many a page of his oeuvre. The poems in Baborer Prarthona (Dey's, 1976), Pnajore DnaRer Shabda (Dey's, 1980), and Ekhan Sab Aleek (Dey's, 1996) bear the essence of a unique poetic voice. His style has set him apart from his predecessors and contemporaries. Despite his familiarity with the poetic traditions of the West, Ghosh is not as easily blinded by its glamour like a Buddhadeva Bose. I believe that Ghosh's poems have always been free of the treacly, overemotional language of the hopeless romantic that have unfortunately permeated the works of many notable Bengali poets like Purnendu Pattrea and Joy Goswami.

In 1967, Shankha Ghosh discovered a book in the library of the University of Iowa written in Spanish on Tagore by his muse and friend, the Argentine writer Victoria Ocampo, which had not been translated to Bangla or English before. Ghosh would once again transcend a translation project to an invaluable edifice of scholarship and insight.

Shankha Ghosh had an uncanny ability to reach into the depths of human lives, literary works, and the political climate with astute sensitivity. He would then come out of it astonishingly sober and composed, ready to write about it in the elegant manner in which he did. Reading him one senses his distinct cool voice that has kept a short enough distance from his many subjects—and it was this disposition, this "desirable dispassion", that likely enabled him to get to the core of his subjects the way he did. The sharpness of his essays, most notably his pieces on Rabindranath Tagore, are full of poise and candour. Unlike many Bengali poets, he was never afraid of being overwhelmed by this or any other towering figure above him. Ghosh wrote as freely as he had ever wanted to.

Mursalin Mosaddeque grew up in the small town of Rangpur in Northern Bengal. He can be reached at [email protected]

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments