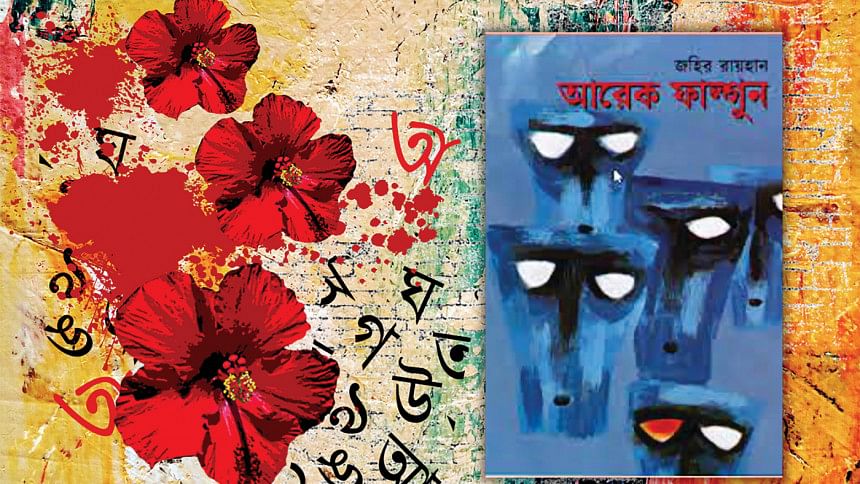

Revisiting Zahir Raihan’s ‘Arek Falgun’ this spring, and every spring

Winter was slowly taking off, with the February breeze following through, with the falling of the Debdaru leaves, with the advent of a new season. A group of well-dressed people, mostly university students, were seen on the streets near the Victoria Park area. Oddly, they were barefoot and came in a group when it was the most dangerous of times to be seen in groups. It was the spring of 1955, and the wind brought with it an air of resistance.

Zahir Raihan starts his book, Arek Falgun, against the backdrop of the tumultuous days of 1955, only three years after the infamous shooting on innocent students peacefully protesting for the inclusion of Bangla as state language on February 21, 1952. Raihan's story spans a short period of three days and two nights, when the students are preparing to observe the 21st of February, in remembrance of the language martyrs. The period of preparation for the events is marked by memories of the movement in 1952, a past spring that was marked not by the red of the Krishnachura, but by that of the martyrs' spilt blood. Based on that experience, the characters of Arek Falgun silently prepare themselves for the worst to come, passing sleepless nights in constant vigilance.

Spring, a season known for bringing lovers together, takes them apart. Munim, a senior in university who is on the frontline of the movement, suffers a fallout with his beloved Dolly because he considers leading a resistance—no matter the intensity or the magnitude—a responsibility that needs to be fulfilled with utmost conviction. Salma, another associate in the movement, suppresses the longing for her husband Rowshan, who is imprisoned in Rajshahi and has lost both his hands during a jail shooting.

What strikes me every time I read this book is how, as in Hajar Bochhor Dhore, or Ekushey February, Zahir Raihan uses fiction to document a people's struggle through the simplest and most personal human interactions. Empathy for each other's struggles brings these youths together for a cause they all believed in. In a way, this too is another form of human love. As one of them says during a meeting, "I cannot forget Barkat's face."

The story reaches its climax when mass arrests rise to the point where the jail can no longer contain prisoners.

"Make more space, Sir," they are heard saying. "Ashchhe Falgune amra digun hobo." "We will be doubled by next spring."

This last line is what brings me back to the book every spring. The conviction to unite against an authoritative power and challenge the establishment, forgetting personal differences, spells the essence of spring for me, thanks to this novel. Arek Falgun was published in 1969 when the people were on the verge of a mass uprising to uproot a military dictator. From the armed resistance in 1971 to the movement against another dictatorship in the independent country in the 1990s to the very recent student movements in the last few years—each time we have been stripped off of our right to dissent, or of a voice, and cornered to the point from where there would be no coming back, authors like Raihan have reminded us to scream and rage against the dying of the light. Spring doesn't just replace the gloom of winter with joy and love. It also brings with it the hope and power of resistance.

Nahaly Nafisa Khan is a sub editor at the Metro desk, The Daily Star.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments