In 'Thug', Mike Dash myth-busts British India’s cult of stranglers

It is nearly impossible to know nothing about the "Thuggee", British India's infamous cult that systematically killed and robbed Indian travelers for hundreds of years. However, almost every write-up available today is an exaggerated horror story that fails to reflect upon the real events. Mike Dash, in his gripping book, Thug: The True Story of India's Murderous Cult (Granta Books, 2005), explores this history through the written record left behind by British officials.

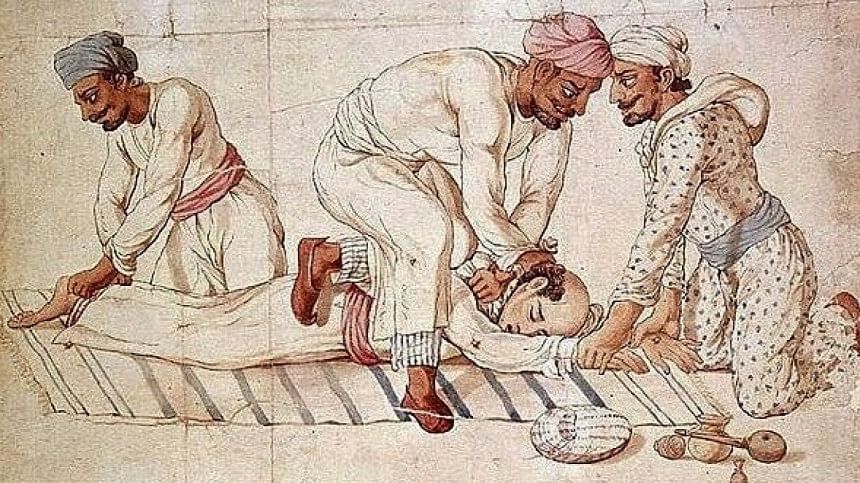

Although many "Thugs"—highway robbers who strangled their victims to death—claimed that their ancestors were involved in these killing rituals since the Mughal period, the early official records come from the 1800s, when East Indian Company officials started finding untraceable dead bodies in Etawah, a city in Western Uttar Pradesh that would become an important site during the 1857 Bengal revolt. In 1811, magistrate Thomas Perry had encountered a group of Thugs by sheer chance. After four days of interrogation, eight Thugs admitted to having murdered 95 people in a matter of eight years. They described a novel way of killing and robbing—befriending their victims and even traveling with them for days to gain trust. Once in a favourable place and condition, a predetermined signal was given, and the victim was strangled with a piece of folded cloth that had a tie on one end (sometimes containing a coin for effect).

It is easier to think of this group of people as degenerate or psychopaths. Yet most of them just took it as a profession; generation after generation stayed involved for the profits the trade yielded.

Thug groups had ranks and divided responsibilities. Some worked as scouts who would gather information on potential targets, some as gravediggers, others as inveigles who charmed and won the trust of their victims, and some, finally, were phansigar, who killed their victims mainly by strangulation. Each year, the group was led out by one Jamadar on an expedition, mostly in winter, when people were most vulnerable on the roads. Some Thugs were high caste and hunted only for bigger groups and prizes. For those with lower demands, even half a rupee was enough to kill a person! Some lay under the protection of the local zamindar, as they would share a portion of their loot with their lord.

Mike Dash's rich narrative looks at this history while shining light on British Indian society and its socio-economic conditions. There is, for instance, a vivid description of the opium trade of India and how the East Indian Company failed to enforce taxes that would've otherwise benefited them. The Company couldn't cope with local traders, smugglers, and bankers. While explaining this, Dash depicts the banking system of India in the early 1800s and how its local bankers (seth) maintained the craft generation after generation. These bankers had great influence in many locations, and when Thugs looted their treasure bearers, the Company had to take notice.

The downfall of the Thugs came by the hand of Captain William Sleeman, who didn't just capture them, but also used them as approvers (state's evidence) and extracted information that would help destroy the entire network. It was due to his effort and request that Ferris Robb, a cartographer, created a skeleton map ranging north and south from Madras to Delhi, and east and west from Calcutta to Bombay. It contained detailed routes which the Thugs preferred for killing and villages where they were most concentrated, among other useful information.

Dash provides some unique information in his book. The lesser-known "River Thugs" were described along with a rising new group that killed just to abduct and sell off children as slaves. Dash also explores the religion practiced by the cult, who are generally thought to be a devious group of solely Kali (Hindu goddess of time, doomsday, and death) worshippers. In reality, almost one in three Thugs were Muslim and most didn't worship Kali in their day-to-day lives; only when they were on a killing expedition.

Contrary to popular myth, there was no Thug stronghold that British officials had destroyed. Thugs that had turned into approvers of the Company were imprisoned at first and afterwards, rehabilitated into community prisons. Dash's account helps clear many misconceptions about this cult, but the reader will also discover facts and stories that will send a shiver down their spine.

Nowshed H Imran is an officer at Bangladesh Bank.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments