Navigating the labyrinth of Bangladesh’s secular identity

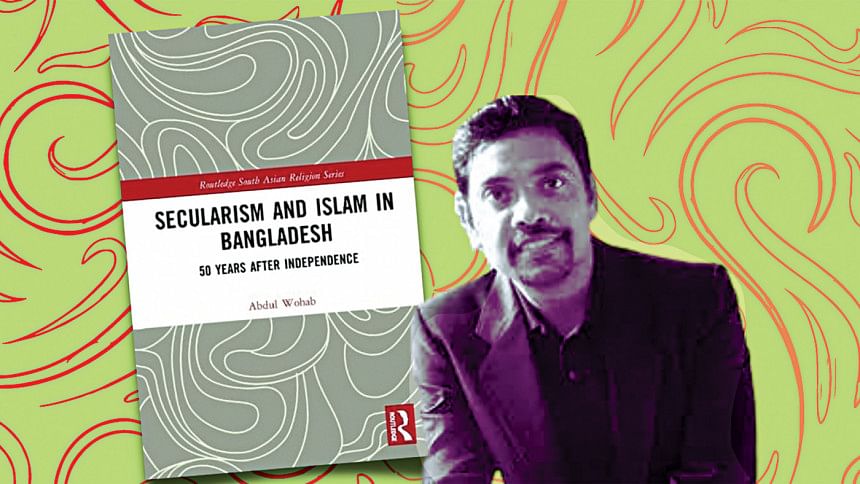

The debate about the constitutional position of secularism in Bangladesh with Islam as the state religion raises one burning question, "Is the country undergoing an identity crisis?" In Secularism and Islam in Bangladesh, Abdul Wohab searches for an answer to this question by exploring the complex interplay between religion and state. Spanning the period from the third to the early 13th century, the book visits the Maurya, Gupta, Pala, and Sena dynasties to show the readers the shaping of the sociocultural scenario in Bengal with the arrival of Muslim conquerors.

Abdul Wohab, who teaches Sociology at Dhaka's North South University, traces the development of cultural traditions associated with syncretistic Islam that embodies the Bengali values of secularism, tolerance, and humanism, and consequently challenges the notion that Islam and secularism are inherently incompatible. He, then, focuses on recent historical events, such as the communal conflict between Hindus and Muslims that led up to the creation of Pakistan, the 1971 Liberation War and the birth of Bangladesh, the banning of Islamic anti-liberation parties in the first Bangladeshi constitution, the August 1975 coup and the resulting revival of Islamic forces that shifted Bangladesh's trajectory from secularism towards a more Islamic state.

Dr Wohab observes, "Secularism...in Bangladesh, refers to the freedom enjoyed by people of all religions to observe their own faith without fear of prejudice or discrimination". This encapsulates the essence of the struggle between secularism and Islam-oriented political forces in the Muslim-majority nation. In this compelling discussion on syncretistic Islam, the incident involving the harassment of a Hindu woman for wearing the "teep" or "bindi" in Dhaka, the hijab ban in France, and the attack on secular bloggers in Bangladesh serve as powerful symbols of the friction between secularism and Islamic fundamentalism, while bringing a vivid and relatable aspect to the academic discourse.

Dr Wohab's inclusion of attitudinal surveys, electoral results, and opinions from key informants (secular and Islamists) enriches the book's empirical foundation. The use of elite interviewing provides firsthand accounts from politicians, academics, activists, and media commentators, offering valuable insights into the current political climate of Bangladesh. Wohab's meticulous research, coupled with his accessible presentation of complex ideas, makes this book a must-read for scholars, policymakers, students, and anyone keen on understanding the intricate dynamics of secularism and Islam in South Asia particularly Bangladesh. However, a more explicit exploration of potential solutions or recommendations could enhance the book's practical relevance in unravelling the complexities of the Bangladeshi sociocultural landscape.

The chapter "Revisiting Worldviews on Secularism and Religiosity: West and Beyond" identifies the Treaty of Westphalia as the symbol of the secularisation of international life. By exploring classical sociology through the lenses of Comte, Durkheim, and Weber, the author acquaints the reader with the gradual disenchantment of the world and the emergence of rationalisation in human life. The juxtaposition of freedom and religion in the first wave set the stage for a thought-provoking discourse on the implications of secularism for modernity and democracy. Conversely, readers are encouraged to reevaluate their preconceptions by the second wave, which emphasises the rising religiosity in the modern world and its sociocultural importance within multicultural Western societies. The discussion, then, seamlessly transitions into the third wave introducing post-secularism and suggesting a paradigm shift in understanding the role of religion in the modern era. Wohab, in his clear and engaging academic prose, suggests that post-secularism may offer a more fitting framework for understanding the immanent role of religion in society.

The book offers a compelling history lesson, and argues that while echoes of historical religious tensions persist within the South Asian diaspora, this study on syncretism may very well serve as a potential catalyst in restoring harmony and overcoming the shadows of past discord by shining a light on the shared heritage of Muslims, Hindus, Buddhists, and Jains in the cultural melting pot of Bengal.

To the reader's delight, Wohab calls a spade a spade and doesn't shy away from addressing the threats posed by extremist ideologies to Bengali nationalism. Be it the assassination attempt on Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina orchestrated by the extremist organisation Harkat-ul-Jihad-al-Islami Bangladesh, the attacks on cultural programs and secular intellectuals such as writer Humayun Azad, the removal of the Lady Justice statue from the Supreme Court building, or the curtailment of free speech by attacking bloggers–all of these incidents encourage much-needed introspection on the country's current sociopolitical climate.

With this book, Abdul Wohab has not only made an invaluable contribution to the literature on the sociology of religion but also challenged preconceptions by initiating difficult conversations. His call for strengthening democratic institutions resonates throughout the book. In debating the future of secularism, he places Bangladesh within the bigger picture of a global perspective by drawing parallels with Turkey, a country with a unique geographic position, lying partly in Asia and partly in Europe. Ultimately, Secularism and Islam in Bangladesh transcends conventional boundaries. The contentious waltz between secularism and Islam sparks intellectual wildfires in a nation wrestling with the delicate balance between tradition and modernity. As Bangladesh stands at a critical juncture, the book stands as a beacon in the sociology of religion, paving the way for a nuanced understanding of secularism in relation to religiosity globally.

Reesha Ahmed is a contributor at The Business Standard and the founder of the youth nonprofit, Share Your Closet.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments