Illustrating Begum Rokeya's ‘Sultana’s Dream’: Interview with Pakistani artist Shehzil Malik

A designer and illustrator whose work focuses on human rights, feminism, and South Asian identity, Pakistani artist Shehzil Malik has just created an artwork based on Rokeya Sakhawat Hossain's novella Sultana's Dream (1905). Daily Star Books editor Sarah Anjum Bari got in touch with Malik to discuss her motivations and inspirations for the artwork.

When and how did you first encounter Sultana's Dream? What made you want to draw your own version of it?

It was my younger sister who shared Sultana's Dream with me years ago. My sister is my go-to person when I need to talk about my feminist ideas (and she also studied literature), so she knew I'd love this story! Other artists have also drawn Sultana's Dream—there is a brilliant rendition by Durga Bai in the tradition of Gond tribal art; as well as a collection of stunning linocuts by Chitra Ganesh. I had seen these artworks earlier but I didn't go back to them when I decided to draw my own version. I was curious with what I would come up imagining a South Asian science-fiction feminist utopia!

In your post on social media, you mention your first impressions of the novella as being "fresh, subversive, and bold". Could you please unpack these sentiments for us?

I think I felt it was fresh, subversive, bold and tongue-in-cheek because even though it's now 2022, we in Pakistan are still arguing over whether girls should be educated; whether it's wrong to marry girls off when they're underage; whether a woman is capable to do a job or become financially independent; whether a good Muslim woman should step out of the house… it feels like the world that Begum Rokeya was escaping, is still the world I live in. If I suggested today that men should be kept in the house, in the wry and no-nonsense way this story is written, I'm sure it would cause an uproar! I'd probably receive a lot of online abuse from men!

And if you think about the times we are living through today, the pandemic has only exacerbated the situation for women. The few freedoms women had--in terms of leaving the house and having a support network—in many ways were snatched away, and the incidences of domestic violence worldwide has skyrocketed. In the early phase of the pandemic, everyone was instructed to stay home—and while the women easily complied, many men refused. It was unthinkable of them to have their basic freedom taken away, and yet they still don't understand why women are angry and dream of a different world.

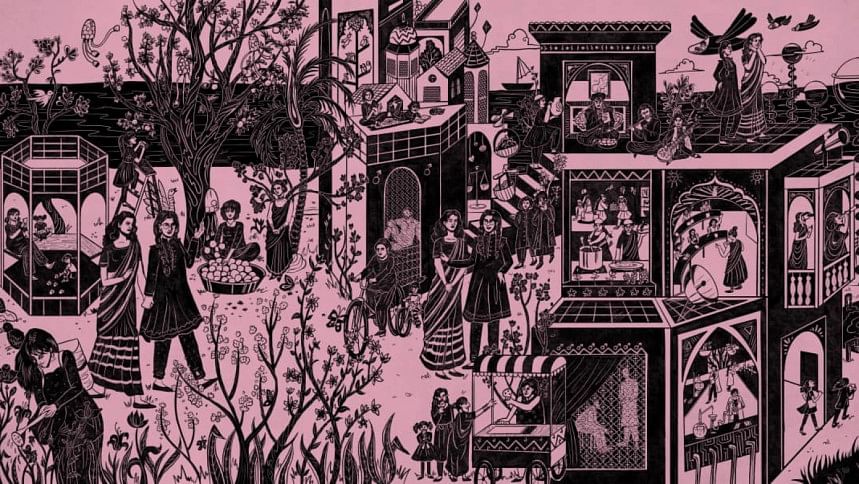

The first thing I noticed in the artwork is the busyness—that sense of countless women engaged in various activities, except that, instead of being taken through the world by the central lens of one conversation, we get to take it all in at once. Was this deliberate? How did you want to portray Lady Land in your work? And how did you conceive of the physical landscape?

Yes the artwork works as a triptych of scenes that come together as a walkthrough of Lady Land. The first scene is the garden, then the hustle and bustle of the bazaar, and lastly the technology that harnesses the power of the weather. Throughout the artwork there are women who are working, studying, cooking, working, reading, and enjoying themselves. It's meant to present a feminist future—one where humanity uses technology to connect to nature, beauty, love and community.

I was inspired by Indian and Persian miniature paintings and their use of space and time. These paintings often show many interactions happening in a single artwork, and take the viewer through multiple perspectives and scales to tell a story. There's no one hero in these paintings, but it gives the viewer the chance to find their own meaning in the artwork. I think combining these pre-colonial methods of artmaking with a story from colonial India—and then drawing the artwork digitally in post-colonial times- it makes me excited to see the possibilities!

Can you tell us about your choice of color palette? Why did you choose to work with pink and black?

I made many versions of this artwork—it went from black and white to full-color—but ultimately there are practical reasons for going with monochrome. I want to print this artwork alongside the story (also translated into Urdu) and give it out to women to read; and it would be cheaper to print in single color. I know pink gets a bad reputation now for being only associated with girls, but the older I get, the more I love pink and the more I see it seep into my feminist art!

As an artist who works with feminist and South Asian identity, what place do you think Sultana's Dream holds in the contemporary landscape of South Asian women's lives? In what way does it speak to our current times?

I think everyone in South Asia (and beyond) needs to know this story! It is so ahead of its time, and talks about the kind of technology we still don't have! It presents a sustainable and ecological future (beyond screens and the kind of dystopian science fiction that is popular today) and really gets to the heart of why we want labor-saving devices and how we can structure our work and relations with others so that it brings us peace. It speaks to everything we are still talking about—in our ideas around social justice and better ways of restructuring this violent capitalist world.

Do you plan on working with any other Bengali or South Asian literary classics that in the future?

I am so excited to research South Asian women writers. I'm reading Ismet Chughtai next. These women wrote literature that was so ahead of its time, and I wish I had grown up reading their works. I'm making a list of women to read. Would love suggestions too!

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments