Partition, 1947—Whodunnit?

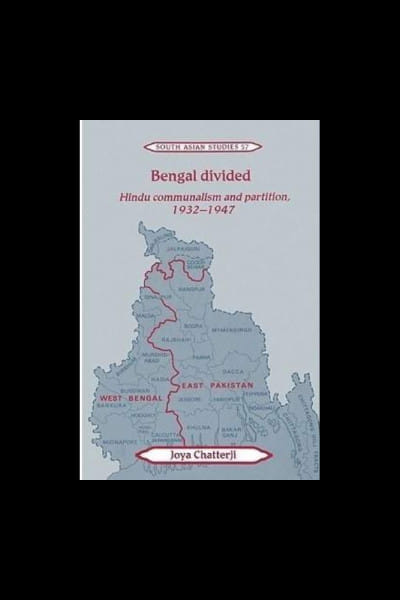

On August 26, 2017, DS brought out a special supplement on the1947 partition of Bengal. It contained fine articles on the subject by renowned scholars from home and abroad. The publication prompted me to look again at Joya Chatterji's acclaimed work Bengal Divided: Hindu Communalism and Partition, 1932-1947. It also nudged my memory back to a day 23 years ago. I was sitting that day in an adda session and chatting with some senior bureaucrats when the book was mentioned by one of them. There was a distinct note of jubilation in his voice when he said that Chaterji had proven conclusively that partition was the work of Hindus; Bengali Muslims had not wanted it!

Seventy years is not a long time for the setting in of a collective amnesia. But here in Bangladesh the partition of 1947 is already a faded memory and is mainly confined nowadays to history text books. Perhaps this is because Muslims of East Bengal hardly felt the brunt of the partition. There is very little creative literature on this side of Bengal which portrays the agonies, sufferings and misery of uprooted communities barring Mihir Sengupta's Bishadbrikhsha. Local research on political history and partition of Bengal was also meager until the 1980s. In the last 45 years, however, many new research works on the partition of Bengal have been published and so we now have a fair bit of knowledge of what the "men at the top" did to unleash the great catastrophe on the people of the region. I would like in this connection to refer interested readers of the subject to Yasmin Khan's book The Great Divide: The Making of India and Pakistan (Yale University press, 2007) as the primer on the subject.

In August 1947 Muslims of India wanted Pakistan but did not know much about its exact shape and size. Leaders of Congress, Muslim League and Lord Mountbatten were deliberately reticent about the subject when they disclosed their scheme for the transfer of power on All India Radio on 3rd June, 1947. Perhaps they were afraid to reveal the truth and apprehensive of the genocide it might trigger on an unsuspecting people who were in a joyous mood and anticipating freedom from British rule. In Chaterji's words, these people did not know what had transpired "in the smoke filled rooms and negotiating tables by men at the top in Delhi who played with the destinies of the millions"

Put simply, Chaterji's thesis is this: Bhadraloks, that is to say, the affluent community of upper caste Hindus, conservative in belief and with customs bordering on orthodoxy, men who constituted the "upper crust of Bengali society" and who lived on income derived from rents collected from landed estates, men, moreover, with English education and control over local bodies and legislative councils, educational institutions, legal system and other professions, including the lower rungs of colonial bureaucracy, did not care a fig about the masses. However, the hegemony of Bhadralok had ended due to changes in the demographic structure of Bengal that began from the early decades of the 20th century when Muslims began to outnumber Hindus in Bengal and when the British gradually allowed a representative government in the province. This phenomenon was accompanied by the expansion of the suffrage because of the Government of India Act, 1935, that put Muslims in greater numbers in the Legislative Assembly, allowing their leaders thereby to eventually govern Bengal.

After the failure of the Cabinet Mission Plan to keep India united under a federal structure in May 1946, the division of the country and Bengal's inclusion in Pakistan became a real possibility. This turn of events posed an existential threat to Bhadralok hegemony. Under these circumstances, their kind of Indian nationalism morphed into Hindu nationalism, and their party, the Bengal Provincial Congress, became indistinguishable from the Hindu Mahasabha. The only recourse left to the Bhadralok then was to demand the partition of Bengal so that they could carve out a secure territory for themselves and retain their hegemony, saving themselves thereby from the disgrace and humiliation of being ruled by their inferiors, that is to say, the Muslims.

To realize this end, the Bengal Congress launched a vigorous campaign for partition and for a separate Hindu province that would remain within the Indian union. Simultaneously, the Bengal Congress mobilized its workers all over Bengal to submit petitions to the All India Congress Committee (the High Command) to put pressure for the partition of the province.

I don't know why Chaterji is so emphatic in putting the onus on the Bhadralok when all evidence prove incontrovertibly that it was actually all "the men at the top" who were responsible for partitioning Bengal and Punjab. Let me present the evidences: Mountbatten arrived on 22nd March 1947 and was sworn in as Viceroy on 24th. On 2nd June Mountbatten, Nehru, Patel, Kripalani, Jinnah, Liaqat, Abdur Rab Nistar and Baldev Sing sat in that fateful meeting where Mountbatten had tabled the detailed plan for the transfer of power and partition which was subsequently endorsed by the seven top leaders of the Muslim League, Congress as well as the Sikhs.

But the June 2 meeting was actually an eye wash. During the intervening period of March and June Mountbatten had held intensive negotiations with the leaders of the League and the Congress and had consulted the governors of all the provinces on the modality of transfer of power and the partition of Punjab and Bengal. The governors of both Punjab and Bengal had opined against the partition of the two provinces. [Frederick Burrows, the Governor of Bengal, had told Mountbatten that if Bengal was to be divided east Bengal would end up as "a rural slum"].

The crucial agreement on the transfer of power was actually reached in Shimla where Mountbatten went on a retreat in early May. After further dialogues between Mountbatten, Nehru, Patel and Jinnah at Shimla, and following Mountbatten's advice, V P Menon, the constitutional advisor to the Viceroy, drafted a plan on the transfer of power on May 16th. This plan spelt out the details of the division of the country into the two states of India and Pakistan on the basis of Dominion Status. According to it, Punjab and Bengal would be partitioned along communal lines to be voted by the members of the respective Legislative Assemblies of the two provinces. Mountbatten flew to London on 18th May to get the plan approved by the British government and returned on 31st May with the approval of the opposition as well as the Cabinet and prepared a statement on the transfer of power.

On the evening of 3rd June Mountbatten made the formal announcement on the transfer of power to the two successor states in a broadcast over the All India Radio. Following Mountbatten's speech Nehru, Jinnah and Baldev Singh spoke accepting the plan. The actual partition of the two provinces was left to a Boundary Commission to be formed later.

How could such a thing happen? Actually, the die for partition had been cast on August 16-18, 1946 in Kolkata, and in Nokhali that October. The Bhadralok had an inkling of what it would be to live under a Muslim League ruled Pakistan. On the other hand, leaders of the Bengal Congress and Bengal Muslim League had lost their clout respectively with the All India Congress Committee and the All India Muslim League by 1940. With the death of CR Das and the ouster of Subhash Chandra Bose from Congress in 1939, the Bengal Congress had been emasculated. This shell of a party had no leverage to force the "men at the top" to accept partition by organizing meetings and submitting petitions when the game had already ended in Shimla!!!

In effect, Nehru and Patel had decided much earlier in June 1946 to have a truncated India by giving Jinnah Pakistan, rather than allowing Muslim League parity in the central government of independent India. They also feared that a federal India with fully autonomous states according to the Cabinet Mission plan would end in Balkanization and that the Muslim majority provinces would join Pakistan.

Our fathers were cheated by a false promise when they joined the Pakistan movement. Nehru and Patel had responded to Jinnah's bluff by conceding Pakistan but had extracted a price for it by partitioning Punjab and Bengal. Now we are squeezed into a territory that has turned into a huge slum where the ecosystem is at peril. No Lebensraum for Bengali Muslims!

Asahabur Rahman is a sociologist and writes on social history, culture and the peasant society of Bangladesh.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments