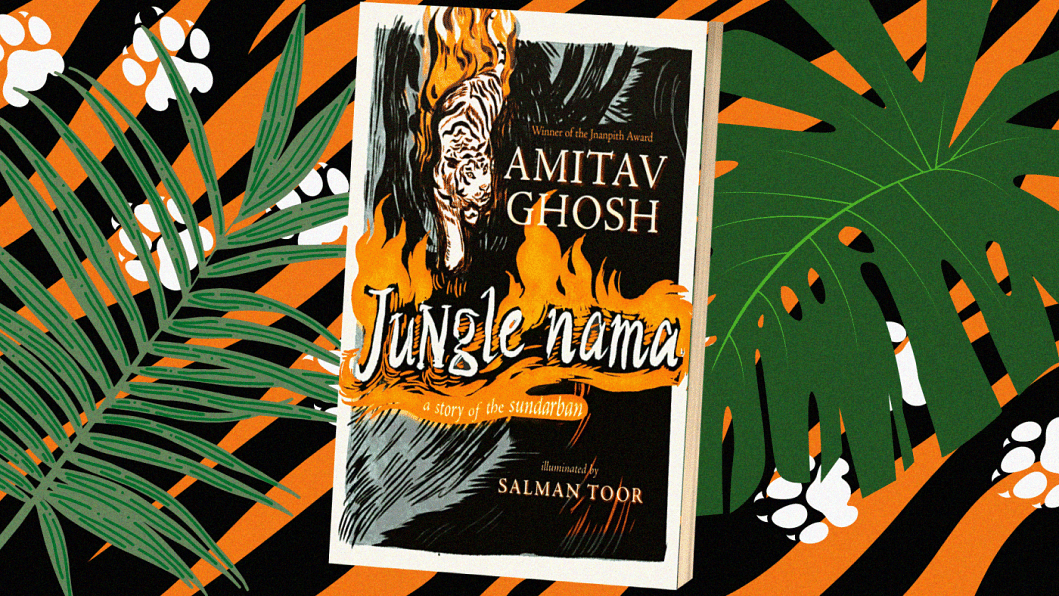

A perennial philosophy: Amitav Ghosh’s ‘Jungle Nama’

Amitav Ghosh's passionate engagement with the Sundarbans has brought out his best as a socially conscious fashioner of narrative in The Hungry Tide (2004) and Gun Island (2019); enriched his intervention in the discourse on ecology, The Great Derangement: Climate Change and the Unthinkable (2016); and perhaps most felicitously, has brought to light the poet he had longed to be. It's worth recalling that his earliest literary attempts had been in verse, on which he sought the opinion of Vikram Seth, his senior at Doon School, editor of the school weekly and already an acknowledged poet. On Seth's advice he abandoned verse and decided to concentrate on fiction and the essay, with conspicuous success. The forsaken waif did not perish, though, and after years in the wilderness has come home, a robust voice confidently impersonating a range of supernatural and earthly characters, to claim his share of fame.

Ghosh's Jungle Nama (HarperCollins India, 2021) is a verse retelling of the core story of the central cultic folk narrative of the Sundarbans, the Bon Bibi Johuranama, available in two late 19th century versions, one by Munshi Muhammad Khatir, the other by Abdur Rahim Sahib. It is intertextually related to the 17th century Raymangal of Krishnaram. Raymangal introduces the tiger god Dokkhin Rai, who is defeated by and makes peace with Gazi Khan and Gazi Kalu, agreeing to share human homage with them. This syncretism is incorporated into the Bon Bibi cult, a unique example amidst clashing fundamentalisms of interfaith solidarity in a shared, inhospitable environment.

Bon Bibi, Mistress of the Forest, and her twin brother Shah Jongoli, King of the Forest, are born to the second wife of a Meccan, and at the instigation of the childless first wife, abandoned to a life in the Sundarbans in fulfillment of a divine plan. Ghosh picks up the narrative at the point where Bon Bibi and Shah Jongoli arrive in the forest and are challenged by Dokkhin Rai, King of the South. They easily subdue their rival, set strict limits to his forest constituency, and assume guardianship of those who have to venture into it for their livelihood. Hence the practice among woodcutters, honey collectors, and fisherfolk of seeking Bon Bibi's blessings before entering the forest.

The stage is now set for a moving drama. Dhona, etymologically "the Rich One", is greedy for more wealth, unlike his brother Mona ("mon", significantly, means heart), who refuses to accompany him with a fleet of seven ships to ransack forest resources. The crew is one short, and Dhona cajoles a poor relation, Dukhey (literally "the Sad-Lad"), a widow's only child, to sign up. Having entered Dokkhin Rai's realm without going through propitiatory rites, they are utterly in his power, subject to fantasmagoric experiences, until Dhona strikes a deal with the tiger god: for shiploads of valuable wax he must leave Dukhey behind to be devoured.

Just in time Dukhey recalls his mother's advice to appeal to Bon Bibi in the verse form of the Johur Nama, for meter and rhyme lend magical power to words. Once more Dokkhin Rai is humbled by Bon Bibi and Shah Jongoli, and is forced to yield enormous riches to his intended victim. Dukhey returns home to find his mother prostrated by grief. Calling her in the magical verse form revives her, and the joy of reunited mother and son is followed by his happy wedding. Ghosh elides the roles of Dokkhin Rai's mother Narayani and Gazi Kalu. The result is a sharper focus. In an Afterword, Ghosh underscores the significance of the tale in the age of climate change. Bon Bibi propagates a perennial philosophy that humankind would do well to heed:

"All you need do, is be content with what you've got;

to be always craving more, is a demon's lot.

A world of endless appetite is a world possessed,

is what your munshi's learned, by way of this quest"

In a fine conceit, the discipline of verse comes to represent the sense of proportion that conduces to contentment; as Bon Bibi lectures Dokkhin Rai:

"Count your syllables, it'll help rein your appetites in,

the yoke of meter will give you discipline.

It's the chaos in your mind that unbridles your desires,

by measuring your thoughts you'll learn to quench those fires."

A few local words are effectively deployed—chukker, nawabi, doosootie, allieballie, dastoorie, all of which ought to have been in Hobson Jobson but aren't—and can be looked up in Ghosh's website.

The most remarkable achievement of Ghosh's narrative is the verse he has fashioned as the equivalent of the quantitative meter of the original. He calls it Dwipodi-poyar, but the adjective is quite redundant. More often, it is simply called "poyar", defined as rhyming couplets with 14 units in each line, and a marked caesura after the eighth unit. These units ("matra") aren't simply syllables, for an "open" syllable like "Rai" will count as one unit; a "closed" syllable like "Bon" as two. Ghosh has couplets of 12-syllable lines that do not conform to any of the accentual meters of English verse. In fact, read with "normal" English intonation, they sound like rhymed prose—quite dull—but belted out like rap, they work beautifully

This prosodic innovation is characteristic of the "New Englishes", whose speakers outnumber native speakers five to one. David Crystal, in his Youtube video "The Future of Englishes", explains that English has traditionally used "stress-timed rhythm", as in iambic verse, while the "New Englishes" follow "syllable-timed rhythm", as in rap. These syllabic rhythms are akin to the Bangla poyar. I recall the great Bengali folk singer Shah Abdul Karim declaring in an interview that rap or hip-hop was nothing new, and was akin to our folk poetry, which he recited by way of illustration.

Ghosh, always thorough in his research, acknowledges a masterly study of the Sundarbans by the poem's dedicatee, Annu Jalais: Forest of Tigers: People, Politics and Environment in the Sundarbans; an informative paper by Sufia M Uddin, "Religion, Nature, and Life in the Sundarbans", in Asian Ethnology, Vol. 78, No. 2.; and for insights into Bangla folk poetry, Thibaut D'Hubert's In the Shade of the Golden Palace: Alaol and Middle Bengali Poetics in Arakan.

I gather Sufia M Uddin has received a grant from the American National Endowment for the Humanities to set up a website dedicated to the Sundarbans, with audio and video recordings of the Johura Nama, interviews, etc. She is reported to have translated the Johura Nama in its entirety. Those who have enjoyed Ghosh's poem will no doubt eagerly await its publication. Sundarbans studies seems to have become a promising subject in Western academia.

A discussion of this attractively produced book will be incomplete without an admiring mention of the artist Salman Toor, whose expressionistic black-and-white pictures have truly illuminated the text.

Amitav Ghosh's Jungle Nama (HarperCollins, 2021) is available for purchase at Omni Books, Dhanmondi, Dhaka.

Kaiser Haq is a poet, translator, essayist, critic, academic and freedom fighter. He currently serves as Professor of English at the University of Liberal Arts, Bangladesh (ULAB).

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments