‘Plants of the Quran’ explores flora dating back 1400 years

The first mosque or masjid in Britain was built as long ago as 1761, some 30 years after George Sale's ground-breaking translation of the Qur'an. That it was built in Kew Gardens gives the game away. It was designed not as a place of worship but as one of a series of orientalist buildings gracing an extensive royal park.

So what shall we say about an exhibition just opened at Kew Gardens to celebrate the launch of an illustrated book, Plants of the Qur'an (Kew Publishing, 2023)? Does it seem strange that a sacred book is being studied for what it can tell us about plant life 1400—and more—years ago?

Dr Shahina Ghazanfar, the author of a series of books on the flora of the Middle East who compiled this compendium, explains: "This is not a religious book but about history and culture. It promotes the pleasure of research and learning, I hope as much for my readers as for myself".

Dr Ghazanfar's researches, part of a long tradition that has sought to elucidate the significance of certain plants named within sacred texts, have been illustrated by Sue Wickison, whose watercolour illustrations feature in the special exhibition.

Both botanists have not only scoured Kew but have traversed the deserts of the Middle East as part of their archaeobotanical research. It has not always been easy to identify which particular plants are those referred to in the sacred texts but they have been able to correct many previous erroneous identifications.

There are some 20 plants mentioned in the Qur'an itself, of which 12 are food plants. A further 54 plants are referred to in the Hadith of diverse Islamic scholars. Most but not all are indigenous to the Middle East or South West Asia. Some will be better known in Bangladesh than others.

Many of the plants covered in Plants of the Qur'an have been recommended by Prophet Mohammed (Peace be upon Him) and/or his scholarly disciples as part of their concern for a healthy diet and medicinal remedies. Increasingly these days, such advice is seen as particularly valuable in terms of sustaining the planet.

Of those plants associated with The Prophet himself, one favourite must be the Lote-tree, which (according to most authorities) he encountered during his ascension into the heavens where, we are told, he enjoyed visions beyond our comprehension.

When you are in the bazaar or kitchen, do you know how many of the vegetables and fruits, herbs and spices you see and use, have an ancient lineage, some much, much older than Islam itself? Cooking lentils as a domesticated plant, for example, has been going on for more than 10,000 years, according to the seeds found in archaeobotanical digs.

Lentils were one of the tastier foods the Israelites asked Moses for when they left Egypt, along with green herbs, cucumbers, or snake melons (exact identification can be difficult), garlic and onions. That makes up a familiar enough meal for most of us, especially when you add in the wheat for chapatis that has been cultivated for almost as long as the lentils.

While many of these foods are reputed to have a variety of medicinal effects, they are frequently said to have value for the soul as well as the body. Among herbs, basil (tulsi) is as sacred as it is nutritious, used in the religious text of the Hadith as a metaphor for happiness in bringing us closer to God.

The same is true of ginger that originated in Southeast Asia. In the Qur'an it is said that it will be mixed in a drink offered as a reward for the righteous as they enjoy heavenly gardens shaded by fruit trees.

As for fruits, one particular species of fig native not to the subcontinent but to the Mediterranean region, ficus carica or anjir, is said to have been a gift of God from Paradise. Practically speaking, it is good for haemorrhoids.

We are all familiar with henna (mehndi) put on by brides, but it can also be used as a cooling paste for fevers, sunstroke, ulcers, and nose bleeds. Henna has a cosmopolitan provenance, much used by everybody from the ancient Egyptians and Romans to the Moroccan Jews.

The grape originates in the Caucasus. Residues in jars show there was wine-making 10,000 years ago in Georgia, a winery in Armenia 6,000 years ago. Even in its non-alcoholic form, it is recommended as a refreshment and still has its uses when soured to vinegar. In Paradise there are said to be two gardens of grape vines surrounded by palm trees and cultivated fields.

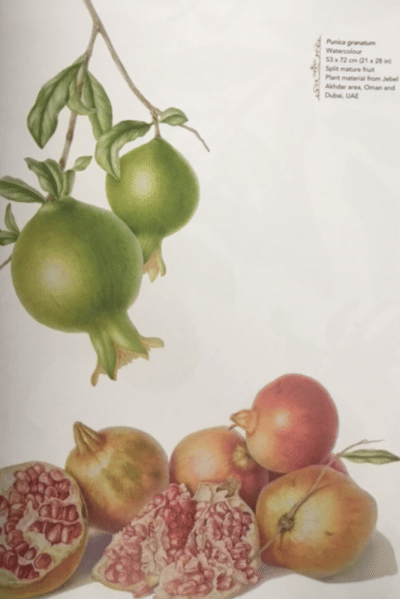

While we don't see all the fruits of the sacred texts ourselves, some are ingrained in our imagination, none more so than the pomegranate. This fruit, also said to have come to us from Paradise, has become a symbol of it. The Spanish city of Granada, home to the Alhambra, a replica of part of which graced Kew Gardens at the same time as the Mosque, takes its name from it.

Botanic Gardens such as those at Kew are thought to have originated in China and at Kew there is still a tall 18th century pagoda, often restored, decorated with dragons. It would be inappropriate nowadays to re-erect the long-gone Mosque—London is full of them now as properly respected places of worship and my hometown of Cambridge has a wonderful new Eco-Mosque.

My eye is finally caught by a painting of that useful plant, the toothbrush tree: kampt (pilu). I had supposed this might be the same as the equally useful neem, but it seems it is not. Looking at Sue Wickison's engaging drawings, I am ashamed of the number of plants I could not identify in their original growing condition. Shame to say, I didn't even recognize the fields of turmeric in Bengal for what they were when first I saw them.

Plants of the Qur'an has an epigraph taken from Ibn Khaldun's Al Muqaddimah: "Man is essentially ignorant and becomes learned through acquiring knowledge". This compendium of intriguing botanic lore is published by Kew at £25.

John Drew is an occasional contributor to The Daily Star. A collection of his articles is due to be published later this year by ULAB Press.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments