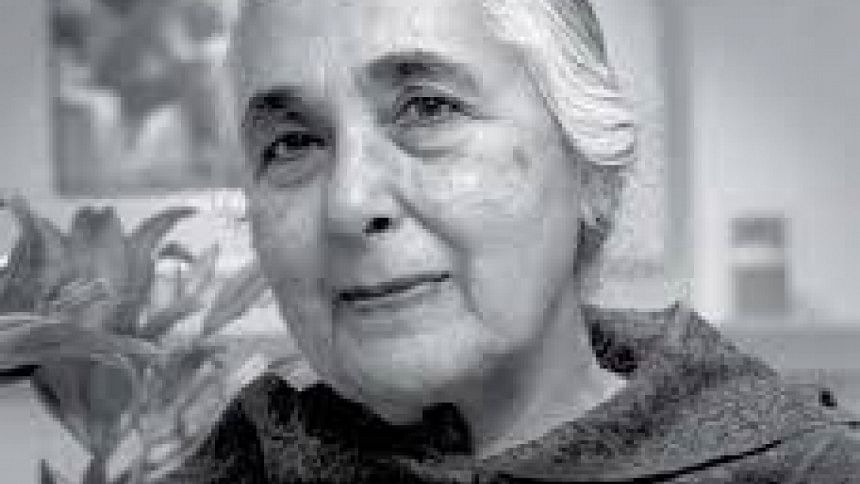

Romila Thapar on why dissent is inevitable

In an interview with Daily Star Books, historian and author Romila Thapar expands on her arguments in Voices of Dissent. She discusses how dissent has evolved through time in the Indian subcontinent, how multi-voiced communities can coexist, and reading material that offers a deeper understanding of dissent in region.

In reading Voices of Dissent and other works you have authored, one has the impression that your work amplifies the importance of voices. Do you agree with this and if so, can you share why this focus on voices is important for understanding dissent?

The importance of voices is not linked only to the study of dissent. In a sense many areas of history are better understood if the historian searches for what more than one voice maybe saying. When I wrote a history of Mahmud of Ghazni's raid on the temple at Somanatha in Gujarat, I used the phrase 'many voices of history' to describe the book as I was referring to the different ways in which this event was written about in the past, in a variety of texts from different perspectives. I was using the term voices metaphorically to suggest that there were many versions of the event and each differed according to the identity of the author and what the narrative was intending to convey. In that sense yes, I do amplify the importance of voices.

This is in part because I also think that the history of an event should not be one-sided but should include as many contemporary or near contemporary versions of and comments on, the event as are available. This may provide a better insight into the event or the historical person. The historian cannot take what is said in any one source literally. The perspective of the author of the source has to be analysed in terms of the historical context of the source and the audience for whom it is written.

We know that the book is an expanded version of essays you have written in the past, so in your experience of turning those essays into a book, have you gained any new perspectives that were overlooked before?

Essays and lectures are individual pieces and tend to focus on a single question involving limited data. Having thought about the subject of dissent at various times, writing this book allowed me to link my ideas and see the nature of dissent as a continuity. This did not mean that the form in which it was expressed was unchanging from one century to the next but rather that the main question was that within changing forms was the nature of dissent recognisable, and was it saying what it had said before or was there a new turn to what was being said. How does one recognise dissent irrespective of the form it takes, especially when its definition emphasizes a non-violent form? This was a distinguishing feature of whatever disagreement or difference with established opinion it was supporting. The question then of why there was a continuity and what were the forms it took, becomes relevant.

Dissent and its relationship with our histories, politics or religion are tricky concepts. So how would you explain the changes in the understanding of dissent in the subcontinent overtime to someone who hasn't read the book?

When there is recognition of the existence of dissent or its potential in the ideas and activities that determine our lives, be it politics or religion, then the articulation of dissenting views in relation to various beliefs and activities ceases to be a tricky concept. If it is suppressed and there is a refusal to recognise it or it is punished in a variety of ways, then it can result in a negative effect. From history we know that sometimes dissent can play a positive role in making a society aware of its problems. Some of the more creative periods in history are precisely those that allowed dissent to have its say – as it were.

Among the forms that I have discussed in the book are two that were recognised and had a deep influence on society and religion and even politics at times. These were the Shramana teachings of Buddhism and Jainism and those of the various Bhakti teachers. Without Buddhist teachings, which disagreed with Vedic Brahmanism, we would not have had an Emperor such as Ashoka Maurya emphasizing compassion and non-violence. Kabir and Ravidas gave Bhakti teaching a wider dimension and linked it more directly to social conditions.

The degree and nature of dissent varies according to what is being questioned and what is being confirmed. Therefore not all the Shramanic sects had the same impact nor all the Bhakti sects. Once they cease to be treated as part of the same umbrella-like religion, their differences will become more apparent and be given the attention they deserve.

Every society will always have dissenting groups, so is co-existence enough to sustain communities (which hold opposing beliefs)? How can we understand this through the lens of, for instance, the dominant narratives of the Mughals in our history?

Co-existence is not enough and a permanent situation would negate its activity. Both affirmation and dissent do not exist autonomously. They are very closely related to the society they emanate from, and to historical change that is happening all along, and in which these attitudes and opinions are participants. The sustaining is done through patronage. In past times the more substantial patronage was from royalty and the wealthy and well-connected. Now of course that continues but it can also be dependent on public opinion and the public support that the ideas attract. Patronage of whichever kind is essential. The Mughals are particularly interesting on the question of who they patronised, since the emperors and the court patronised diverse groups ranging from the orthodox to the dissenters. Royal patronage or the patronage of those in authority is of course heavily tied into the politics of the times.

Akbar's religious patronage for example, included some established groups but also extended to some that belonged to sects that had originally been dissenters. This included some Sufi sects, some Jaina sects, as well as some non-Vedic Hindu sects. Akbar's patronage was eclectic as also was the break-away religion that he tried to establish, what came to be called the Din-i-Ilahi. His dissent was an attempt to find that which would bind people instead of religion separating them. It is also worth remembering that he had strong bonds with upper caste Hindus. The higher status Rajputs gave their daughters in marriage to the ruling family and significant administrative appointments in the empire were often held by brahmanas, kayasthas and Rajputs.

For Aurangzeb religions were distinctively different. His attitude was far more political. This is reflected in the mosques he built to replace prior temples to demonstrate his power to the patrons of the temples who were not his political allies. Yet where it suited his political ambitions he was ready to patronize upper castes and Hindu institutions, as is clear from the farmans he issued granting land to brahmanas and to institutions such as those of the Nath Yogis of Jakhbar and other places.

Do you believe fiction can also offer a lens for understanding voices of dissent? If you had to recommend fiction (from other media) in order to understand these issues with more depth – which books or authors would you suggest? Any recommended reading for those wanting to learn about the history of dissent in the subcontinent?

Fiction can certainly offer a lens for understanding voices of dissent. Much of fiction reflects the society from which it emanates. Therefore if the author wishes to introduce ideas of dissent this can be done both in the characterisation of the protagonists as well as in their dialogue. It can even be included as part of the narrative. It is difficult to suggest books as one has to think about the particular cause of dissent in order to choose such a book.

There has not been much detailed discussion on dissent per se in relation to pre-modern India. Dissenting ideas are generally included as part of the encompassing arc of a religion. Nor has there been extensive writing on the interface of the many religions present in India and how this interface, where it actually occurred, impacted the further history of the religions and societies experiencing the closeness. There is a tendency as far as possible to treat religions as distinctly different and yet there are some significant overlaps in every religion with other religions. So ideas of dissent have to be garnered from the studies of the various religious sects that existed in the sub-continent.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments