Sad girl lit and trivialising women’s writing

When I read the title of Charlotte Stroud's article "The curse of the cool girl novelist" and the accompanying description of said type of novelist, I had a solid image of what she was referring to. Stroud describes "cool girl novelists" as "depressed and alienated", "incurably downcast", and "terminally sad". It had similarities with "sad girl" literature, a supposedly new genre captivating readers and publishers alike.

Sylvia Plath, Otessa Moshfegh, and Sally Rooney are the names that commonly come up when you think of this aforementioned genre. Type 'sad girl novels' into Google, and a string of articles will turn up. I came across a post on Reddit which asked if the "hot/sad girl" is a new genre. In the comments to that post on r/books, a remarkable amount of diversity could be seen in the content of the books being mentioned. They ranged from addicts, depressed women, 'a friend who is a serial killer' to tradition bound parents pushing for marriage.

As might be evident from this article even being written, I have issues with this label of the sad, mad, or cool girl novelist, because the term "sad girl" works to erase, exclude, and distract. It is a term that flattens and shapes perceptions before one has read the work.

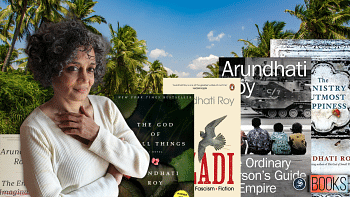

A mere cursory look at blurbs and reviews of texts by the authors Stroud mentions shows the sweeping generalisation placing women writers talking about Grenfell, inequality, racism, colonialism, substance abuse, and romances with power imbalances, under one category, as if one commonality in their works renders the rest of the work unworthy. In what I felt was one of the most telling parts of the article, Audre Lorde is included without any further caveats with Sylvia Plath, as if the writings of these women can be compared with ease. Additionally, think for a moment, what the reaction would be if The Catcher in the Rye (1951) and The Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man (1916) were called "sad boy novels". It would be scoffed at, and rightly so.

This is not to say that there is no validity to the feeling that there is a tonal similarity in the novels recently being published. In a 2023 article in The Guardian by Sarah Manavis, authors who could be categorised as writing "sad girl" literature point out the flaws themselves: the protagonists are often privileged, white, middle-class, millennial women; the issues faced are never "truly sinister"; the assumption that there is a "general female trauma" that underlines life as a woman.

A 2019 article by Leslie Jameson also considers this issue. In it, the very valid problem of seeing happiness as lacking depth is mentioned, and the issue of writing about suffering as if it's only individually experienced is also discussed.

The supposed sad girl novel might seem repetitive, and in a world where our senses have been dulled by an endless onslaught of audiovisual content, seeing the same kind of books being pushed by publishers can strike a nerve. But we must look at why sadness is so pervasive in novels about these relatively comfortable and often relatable characters.

Determining whether a traumatic incident is severe enough to warrant behaviour that might be described as messy and childish at best, to petty and repulsive at worst is a contentious issue, not least because the usually thin, white, middle class protagonist is insulated from the myriad systemic issues poorer women of colour are not.

Stroud, who notably veers off from others criticising this genre by including authors who are women of colour, ends her article writing, "Everyone's tired of your turmoil." It made me think as to what expressions of sadness we were willing to deem exhausting, and I kept thinking of the Bangla word most often directed at young women: "dhong."

Online discourse frequently coalesces Gen Z and millennials, leaving out the vastly different experiences with new technology those placed in the two groups have had. I grew up without reaping the benefits of the massive push to destigmatise mental health issues that many younger Gen Z—a group which I belong to—have benefitted from. And so I grew up hearing the word "dhong" when I expressed vulnerability without realising the function this word served. Much like Stroud's assessment of the cool girl novelist, "dhong" refers to a pretence, suggesting that the expressed vulnerability is an act meant to garner attention and sympathy and hence should be shut down and ignored. In trying to understand this reaction, what I have found particularly useful has been the description of pain as a signalling device. If sadness is being expressed, what is being indicated, and what is being revealed?

These dismissals of sad girl novels result in a refusal to see, listen to, or understand women. It is a convenient bulwark that allows for the easy avoidance of inconvenient truths regarding women who, despite their privilege, are at odds with the modern world. It is as if there is an underlying discomfort at what is being indicated by these sad/cool girl novelists—that the present world continues to induce suffering, even on the comparatively privileged people we can relate to, people not in unfathomably inhumane situations such as those shown in breaking news coverages.

Determining whether a traumatic incident is severe enough to warrant behaviour that might be described as messy and childish at best, to petty and repulsive at worst is a contentious issue, not least because the usually thin, white, middle class protagonist is insulated from the myriad systemic issues poorer women of colour are not.

The situation is very much akin to what Betty Friedan's The Feminine Mystique (1963) lacked, but also crucially revealed through its inclusion of only unhappy white women. Its selection of only the society's norm and also ideal laid bare the many problems of long-cherished beliefs and institutions such as marriage and motherhood we so strenuously enforce as the norm. We therefore have to ask: is the sad girl novel doing the same for some other strongly held belief? In many ways, the alienation and disaffection so common in sad girl novels with comfortable white protagonists can be read as manifestations of living an atomised life under late capitalism. Does the "sad girl" novel then reveal the exhaustion that comes from such a system? And does it further reveal the more uncomfortable reality that the more privileged have become docile in the face of such an existence? When the self-help industry has ballooned to US$ 41.2 billion, is the sad girl novel the other side to this phenomenon where happiness seems elusive?

Sara Ahmed in her examination of happiness, and subsequently unhappiness, writes, "The freedom to be unhappy would be the freedom to live a life that deviates from the paths of happiness, wherever that deviation takes us. It would thus mean the freedom to cause unhappiness by acts of deviation". Seen in this light, sad girl novels can be read as a rebellion, even if a meek one, against culturally entrenched ideas of what we ought to do.

Aliza Rahman has problems keeping her work short and fully acknowledges it. Give her tips at [email protected].

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments