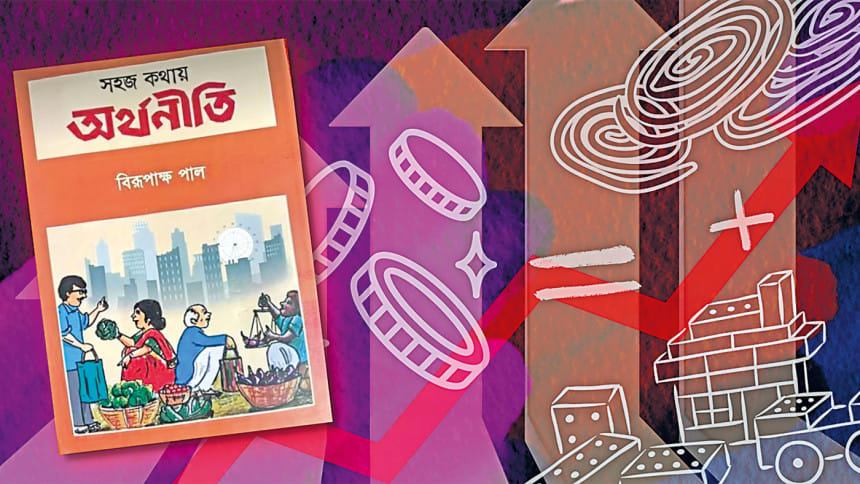

‘Shohoj Kothai Orthoniti’ A localised flavour of economics

Flipping the pages of a textbook often makes me feel like I'm trapped in the US. We studied economics from an American lens, using American textbooks, where examples were about hotdogs and the case studies featured Fords or McDonalds. In the crowd of economics books that do not represent our experiences at all, Shohoj Kothai Orthoniti is a pleasant deviation. In this book, Birupaksha Paul locates the laws of economics in the chaos and humdrum of a rural bazaar, in cinema halls, or in the festivities of Ashtami mela.

The cover features an illustrated snapshot of a vegetable market where a woman is selling cabbages to a buyer who's standing with his index finger raised in the air—probably a gesture to strengthen his position in the bargain. Just beside them is another seller, weighing eggplants on a mechanical scale while the buyer eagerly awaits. This close interaction of individuals carries the essence of microeconomics—one of the two major sections of this book. The other section is macroeconomics, which is reflected in the receding backdrop of a cityscape where we see the buildings in aggregate, from a distance. While the topics discussed in the book, or the division of microeconomics and macroeconomics is nothing new, the translation of the two terms are. Microeconomics has been translated as "onumatrik orthoniti" instead of the widely used "byashtik orthoniti" and macroeconomics has been written as "byaptik orthoniti" instead of "shamoshtik orthoniti".

It's not only the terms that have been translated from English to Bangla. Birupaksha Paul has attempted to translate the core of the concepts by moving away from West-centric narratives. He takes us to his childhood when his father used to give him two taka for the Ashtami mela. Paul explains how he used to allocate the pennies between toys and jilapi, what would happen if he overspent, and whether he had the option to borrow. This light-hearted story becomes an analogy for national budgeting. We picture our writer standing in front of the cinema hall, staring with curious eyes and a great desire to watch a movie yet no demand for it because his pockets were empty!

The attempt to make economics interesting to laymen is not new. What gives economics the potential and power to be relevant for anyone is that it is a tool to make better decisions. Freakonomics (William Morrow, 2005) created a global phenomenon by applying the methods of economics to answer questions that are seemingly unrelated to economics. We Bangladeshis have our Porarthoporotar Orthoniti (UPL, 2017) by Akbar Ali Khan. He takes snippets from different fields of economics and seasons them with incredible wit. The pages only become cheerier whenever frequent visits are paid by the humorous Nasruddin Hojja. Birupaksha Paul too borrows from the wisdom of scholars outside the field of economics—Lalon, Socrates, Vivekanand, and a few more. Compared to Freakonomics and Porarthoporotar Orthoniti, what sets Shohoj Kothai Orthoniti apart is its focus on theory. While the other two books delve into real cases and view them through the lens of economics, Paul's book explains the concepts of economics from a local angle. The examples used in this book are also mostly analogies. Real life examples, when used, do not entail an elaborate analysis. Needless to say, the book comes with a fair risk of oversimplification.

For those who dread and despise equations and graphs lurking in the pages of economics textbooks, Shohoj Kothai Orthoniti can feel like a breath of fresh air. However, we have to keep in mind that the book gives an overview of a lot of concepts but doesn't delve deep into any. Quite true to its title, it explains economics in simple terms. This makes the book a helpful guide for those unacquainted with the field. For those who have already studied introductory economics, the only incentive to read this book would be to savour a localised flavour of the discipline. If we assume Shohoj Kothai Orthoniti to have set out with the intention of making economics easy and interesting to students, it accomplishes the first goal with greater success.

Birupaksha Paul mentions in the book that John Maynard Keynes, the economist who theorised a possible way of recovery from the Great Depression, was called a "common sense economist". Shohoj Kothai Orthoniti argues for the cause of common sense. While mathematical sophistication certainly has its place in economics, students are often warded off by its obscurity. Shohoj Kothai Orthoniti makes an important contribution by making economics easy and accessible to young students. It gives them the power to think about economics.

Noushin Nuri is a contributor.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments