Snapshots of history—Golam Mustafa meets Manzoor Alam Beg

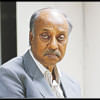

A history of Bangladeshi photography would be incomplete without the stories of Golam Mustafa—the first Director of Photography of Bangladesh Television, the first person to produce a commercial film using the U-matic format in post-Liberation Bangladesh.

Born on November 30, 1941, the Ekushey Padak-winning photographer was among the first batch of students at the Begart Institute of Photography and a founding member of the Camera Recreation Club, Bangladesh's first photography organisation.

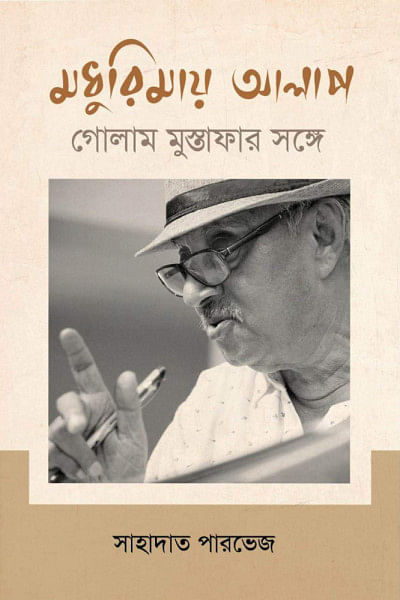

Modhurimay Alap (Swapno '71, 2023), released at the Ekushey Boi Mela this year, transcribes two days of conversations between Golam Mustafa and Shahadat Parvez, a photographer, teacher, and researcher who is currently Photography Editor at the daily Desh Rupantor. Their discussions take the reader through Mustafa's youth during the 1947 Partition, the documentation of Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman's homecoming, Bangladesh's place in the world of photography, the revolutionary phases of East Bengal photography, and more.

In this excerpt, Golam Mustafa shares how he first became acquainted with Manzoor Alam Beg, considered to be the Father of Photography movements in Bangladesh.

Shahadat Parvez (SP): How did you get to know Manzoor Alam Beg?

Golam Mostofa (GM): I was trying to catch a bus one day when I noticed a studio—Roxy Photo Service. A few large photographs hung on the walls inside. I went in to look around and found a man standing at the counter, fervently puffing a cigarette. He was thin, bearded, dark complexioned; he had a very interesting face.

"I have a few negatives that I want to print. Can I do that here?" I asked him.

"You can", he said.

"Will you do it for me?"

"These are a bit oversized. It's alright, I will manage with some paper", he said after looking at the negatives.

I went back to the studio the next day. "I've printed your photos", he said upon seeing me. "But let me keep it for another day. This needs softer paper for better quality print."

Of all the studios that had printed out photos for me, no one had ever asked to keep them with such interest and compassion. I left the images with him and returned the next day. There was a world of difference between the two sets of photos. He explained to me why the quality differed.

The man wanted to know what I did, and then he looked at my camera. "This is an ordinary camera", he told me, "but you can produce good work with it if you read the manual closely."

I spent all of that night with my camera on my bed, reading its manual page by page. I went back the next day and told the man that there were three points I hadn't understood.

Beg Shaheb realised that a lot of customers came to him, but I was no customer. There was a certain madness to me.

One winter, I clicked a picture of the old high court building. Do you remember it? It is still there—the one in front of the Eidgah field. There was a vast lake there. A beautiful lake with clear water. The peak of the high court building would reflect on the water body. I couldn't perfectly capture that reflection in the picture I had taken. I showed it to Beg Shaheb.

"This picture can't be taken like this", he told me. "You have to climb at least 20 feet. Try putting up a ladder against the tree in front of the building."

Trust me, I wouldn't dare to do it now, but the next day—on a holiday—I managed a ladder from a friend of Beg Shaheb's from the Crescent electrical shop on the east end of the Topkhana Road.

Four people brought in the ladder and set it up against the tree. I got up on it and saw…

SP: Have you gone back to that scene now?

GM: Yes, I can see it in front of me. I can see the peak of the high court reflected on the water.

I often tell my students that you can see more with your eyes closed than when your eyes are open. It is when you reach that stage that you know you are a photographer.

They don't understand what this means. They say, "Sir, how can we see with our eyes closed?"

I tell them that if you have your eyes open, you only see what is in front of you. If you close your eyes, your horizons expand.

I see it now. I climb up as those four people hold the ladder for me. The higher I climb, the more the ladder rattles. My camera hangs by my neck. There are 12 exposures, and I capture all 12. I switch right and left, change exposures and capture images. Beg Shaheb had asked me to change the stop and capture pictures. I fix my shutter speed to 125 and click pictures on F-22, 16, 11, 8 and 5.6.

The next morning, I reach Beg Shaheb's studio very early out of excitement. He arrives on his Suzuki motorcycle and asks me, "Oh, Mostafa. You are here already? Didn't you go to university today?"

"I will go after I develop my roll and observe the negative", I tell him. "You had asked me to try to take a picture of the high court from atop a ladder."

Beg Shaheb opened the dark room in the back. The madness of my excitement had gotten to him by then. He didn't even submerge it in water after fixing it.

"It has happened. You pulled it off", he tells me. "You can go to class now. I will print out the best shot from your negative by this evening."

I sat in class for what felt like forever. I looked at my watch constantly. Finally, finishing my class, I rushed to the studio. "Your picture is done. It's being dried in the studio", Beg Shaheb told me.

He had printed a panoramic view on a 12 by 16 inch paper. He said, "I will put this up in the studio. You took the picture the way I recommended, so this will be here in your honour. I will print out a smaller one for you."

I became his student on that day.

I took pictures alongside him, went to different places, had both good and bad experiences. I was with him beyond life and death. And that picture of mine was in that studio until the very last day.

Translated from the Bangla by Hrishik Roy and Sarah Anjum Bari.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments