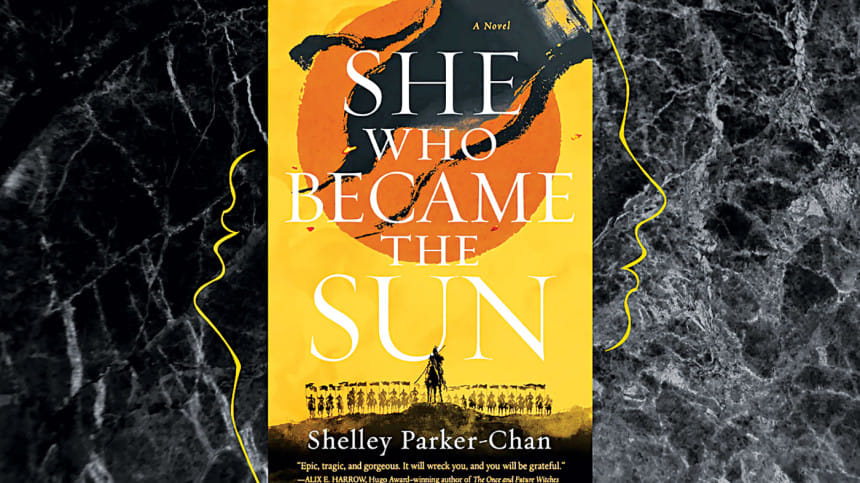

Shelley Parker-Chan’s 'She Who Became The Sun': A song of identity and fate

Identity is mercurial: it shifts and morphs into a new being at the change of a breeze. That change is glacial, and often happens on its own volition; but one can also grasp a new identity, hold it tight till it engulfs the old, and thereby change the trajectory of their life completely. We saw this in Disney's Mulan (1998), and thus is also the tale told in Shelley Parker-Chan's She Who Became The Sun (Tor Books, 2021).

The novel is set in a vaguely fictional 1300s' China, as a reimagining of the rise of the Ming Dynasty. It follows two tales inextricably connected. The first is the tale of a peasant girl whose destiny is ordained to be nothing, while that of her brothers is to be great. When bandits kill her family, she dons her brothers' name, Zhu Chongba, and joins a monastery to survive, hiding from the powers above. But when the monastery is razed by the occupying Mongol armies, she realises there is no safety in hiding, and embarks on a path to seize her brothers' destiny too. The second tale is that of the eunuch general Ouyang, the very general who burns Chongba's monastery to the ground. Born Chinese, but raised by the occupying Mongol nobles, Ouyang's tale is one of grappling with identity, with insecurities, and shaping one's sense of self against the preconceived notions of those around them. Throughout the book, Chongba and Ouyang act as narrative foils for one another, asking similar questions but reaching wildly different answers because of the different eyes through which they see the universe. Neither are right, neither are particularly good or bad people either, but their flaws are what make them interesting, and human.

For those familiar with Mulan (1998), She Who Became The Sun follows similar beats, albeit more nuanced, evolved, and far darker. Do not, however, expect the grand action set pieces in the beloved Disney classic. Like Tolkien, Parker-Chan is not concerned with the grand battles and heroic moments. They happen, but they are dwarfed by moments of character and introspection. The novel is quite transparently a tale of identity: shaping your own space in a world that does not want you, and making that shape yours despite what others think you should be. It is a tale of gender identity: what it means to be a man, what it means to be a woman, and what it means to be both at different times, or neither, or beyond gender itself. This it does brilliantly through the many viewpoints of characters, none of whom fit into the world they live in. It is a tale of how, with enough ambition, one can wrestle destiny into the palm of their hand. It is about legacy, about having a tale to leave in your wake, and the cost of achieving such greatness. It is about defiance and revenge against a universe that wanted you gone, and against the people it used to enact its will. It is most of all about being true to yourself, no matter what the world wants of you.

If this description makes the book sound sombre, then your assessment would not be too far from the truth. While there are a few dry jokes and a smattering of beautifully heartfelt moments, Parker-Chan keeps the tone mostly subdued, without crossing the line into morose. For someone like myself who is more used to fast paced fantasy, this was hard to get used to. The gravity of tone is also exacerbated by some spectacularly gruesome deaths. Suffice it to say, this is not a book for the squeamish. But the heaviness is offset by the sheer beauty of the descriptions, and how they often mimic the characters' inner states. The prose swells into poetry in those moments, captivating the audience with gorgeous vistas that are mirrored in deep personal reflection. As Zhu contemplates the nature of "greatness" from the top of a mountain, we are drowned in the world she sees, "where chaos and violence boil[ed] under the tidy patterns of green and brown, and [she] knew that as much as that world contained the promise of greatness, it contained the promise of nothingness". Parker-Chan, however, makes sure not to never overdo it, for there is only so much poetry one can take before the writing is bogged down.

As someone who has been clamouring for more fantasy stories set in Asian settings, this is a breath of reprieve, even though the fantasy elements in the story are small, and the tale itself is more historical fiction than fantasy. She Who Became The Sun is the first in The Radiant Emperor duology, and we cannot wait for the finale of this epic tale.

Yaameen Al-Muttaqi works with robots and writes stories of dragons, magic, friendship, and hope. Send him a raven at [email protected].

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments