Sri Lankan lives in turmoil: A riotous rendition of “Funny Boy”

My encounter with Funny Boy (Penguin Books, 1994) was comical. The book was lying innocently on the desk of an ex-colleague who had left months ago. I felt an instant connection to the book cover—a sunset at sea—as soon as I laid my eyes on it. Or maybe I am only justifying stealing a book in broad daylight. Anyway, I did ask the other colleagues sitting around said desk before pocketing the book.

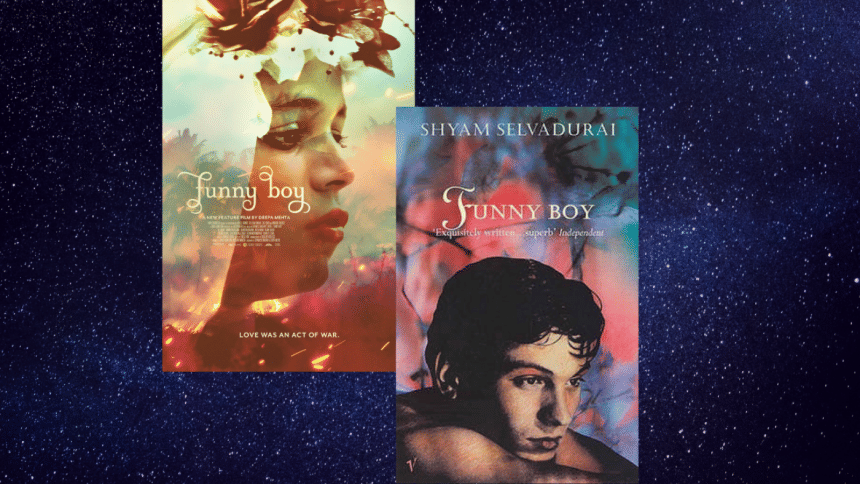

I had never read anything by Shyam Selvadurai before and therefore was pleasantly surprised at how his words flowed so effortlessly, unfolding childhood memories and weaving nostalgia. I devoured the pages, Iiving every moment with the protagonist Arjie, unable to put the book down. And soon, in a conversation with another colleague, I found out that the book was made into a film by Deepa Mehta in late 2020.

Selvadurai's book, set against the backdrop of escalating political tension in Sri Lanka prior to the 1983 riots, portrays the effect of the Tamil-Sinhalese clash on the personal lives of his characters, before giving a glimpse of the riots in the very last chapter. Deepa Mehta picks up some of these characters, sharpening them and making them more vibrant on the screen.

Unlike most adaptations, Funny Boy the film complements the book instead of competing with it. To me it seemed like an interesting teaser that encourages people to also read the book. And Mehta does a good job of pointing out that a story need not be unfolded verbatim from its source material for it to make sense. The details of the book still fresh in my mind, I could not help but be awestruck by the cinematography and the choice of location. Arjie seemed to come out alive from the pages and dance with his favourite Radha auntie on the screen. Arjie's unusual ways, which were reprimanded by his other family members, were embraced and encouraged by Radha, who acted as a strong pillar when Arjie finally came to terms with his sexuality. Radha's own love story with Anil, with its heartbreaking ending, gives a powerful background to the story. This spontaneous flow, however, only lasted for the first half of the movie.

Throughout this first half Mehta's witty changes to the text's dialogue and her additions to attributes of the characters offer a splendid match with the evocative atmosphere of the book. She chose to use some of the most important dialogues from the text. From "because the sky is so high and pigs can't fly" to "you've got a funny one here", Mehta acknowledges and ensures that the turning points in the story are portrayed correctly. Nonetheless, the second half, which is supposed to portray insurgence, becomes chaotic on the screen. The scenes go by much too fast, as if in a rush to finish, failing to touch on anything specific. The role of Jegan Parmeswaran, for one, need more fleshing out. Even though Jegan's association with Tamil Tigers—the militant group that fought the Sri Lankan Civil War against the national government—is alluded to, his involvement in plotting the assasination of a politician does not find a place in the movie.

Mehta's depiction of almost perfect characters makes a foreign language film easy to watch. Even though it was disappointing to see her leave out some of the characters, it was nonetheless interesting to see how she made the story flow without them.

Her rendition of little Arjie, Radha, Anil (Radha's lover), Nalini (Arjie's mother) is met with brilliant acting from the artists. The portrayal of older Arjie, Shehan, and Arjie's dad, however, needed more work. While little Arjie questioning the do's and don'ts of boyhood is immaculate, older Arjie exploring his sexuality with Shehan seems nowhere close to how beautifully it is illustrated in the book. The film misses out on portraying Arjie's extremely visible outburst of his changing status in society—from a rich boy to that of a refugee.

Oyessorzo Rahman Chowdhury Prithibi is a contributor.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments