Tagore’s Gitabitan and the bookshelf of a Bengali household

It has been 81 years today since Rabindranath Tagore, a Bengali polymath, poet, composer and the first Bengali Nobel Laureate, breathed his last. In these 81 years, much has changed in the world, including the modernisation of his compositions. Tagore's songs—Rabindra Sangeet, as they are known—are still popular amongst Bengali music lovers. A quick search on YouTube will lead to the traditional renditions that we have grown up with, along with the younger lots reinterpreting the songs into acoustic, unplugged, and piano renditions. Tagore's music lives on and he lives on through his music.

Earlier in this column, I have written about shelves—how they represent the ideas of generations and also the significance of family. A mandatory piece of furniture in the room, especially in South Asian culture (where digital books have not penetrated completely as yet), the bookshelf is usually dominated by the most avid reader in the family. In a typical household, the shelf stays while the books change, from picture books and bedtime stories, to guide books for board exams and gifts of poems and essays, depicting life and it's many chapters. One book that would forever stay on the shelf of a Bengali family, particularly one in the 1990s, sometimes collecting dust along with the religious scripture, is the Gitabitan (1932) by Rabindranath Tagore.

One would think that the Gitanjali (1910), yet another bundle of verses by Tagore, would occupy the shelves instead. After all, it is the book, or rather the translations of his 157 poems, that won Tagore the Nobel prize for literature in 1913. But many families in the '90s, when art, music and culture were still significant for Bengalis to become all-worldly individuals, would invest in the Gitabitan instead.

This might have been because back in the era of the no-internet and social media (I like to call it "the era of the happily oblivious"), the highest form of achievement was, other than scoring 'star marks' and 'stands' in board exams with their 'letter marks', the ability to recite poetry from memory, attending music classes on a regular basis, and spending years auditioning for the BTV and Radio Betaar enlistments as singers, musicians, voice artists, actors, poetry reciters, and so much more. For such people, the book was essential.

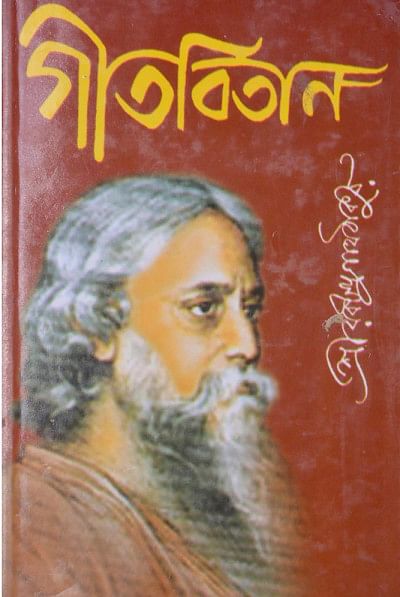

The Gitabitan is a complete collection of all of Rabindranath Tagore's 2,232 songs, his Rabindra Sangeet. One of its most unique features is how all the poems have been categorised into six themes: Puja (worship), Prem (love), Prakriti (seasons), Swadesh (patriotism), Aanushthanik (occasion-specific), Bichitro (miscellaneous) and Nrityonatya (dance dramas and lyrical plays). The thick book covered in red was the typical edition from the 1950s that most families would keep on their shelves back in the '90s. Today the book is a little smaller, with typed prints, though most refer to the songs and lyrics of the Gitabitan online.

Nothing less than a good history lesson, some of the songs from the Gitabitan, especially the ones from the Swadesh category, refer to Tagore's love for his country, for Bengal, while some songs from Prem have supposedly been inspired by the many love interests that he had had in his own life—some being slightly controversial as well!

An all time favourite is Jodi tor daak shune keo na aashe tobe ekla cholo re, which represents hope and the strength of the individual; of how one must move ahead despite rejections and no support from society. It is a song that has inspired soldiers of the past, women breaking barriers, and young changemakers of today. Even though this song has always been a part of the most popular Tagore playlists for many years, it became all the more popular in contemporary times when the legendary Indian actor Amitabh Bachchan recorded it for the end credits in the movie Kahaani (2012) by Sujoy Ghosh.

Yet another poem that is worth mentioning from the Gitabitan is Khelaghor baandhte legechi, a song filled with symbols and interpretations that some read as happiness and youth within the words of the "house" which he tries to build within himself; and many read the sorrow between lines of heartbreaks and rejections.

Even though some of us can't help singing the tunes when we read these poems, the Gitabitan is a good read for aspiring Bengali writers and book lovers. It is where Tagore has successfully concocted words and sentence constructions and has proven that aesthetic beauty can become a part of word play.

Check out a Gitabitan today from your favourite bookstore and think about adding it to your list of daily reads on the shelf. The timelessness of the words and the tunes will encourage you to improvise, to feel inspired, and appreciate beauty in all that you experience.

Elita Karim is a journalist, musician, and editor of Star Arts & Entertainment and Star Youth, The Daily Star. She tweets @elitakarim.

For more book related news and views, follow Daily Star Books on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, and LinkedIn.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments