Tales of a development sector doyen

The New York Times once termed BRAC as "the world's best kept secret". But Ahmad Mustaque Raza Chowdhury knows BRAC like the back of his palm.

Persuaded by the late Sir Fazle Hasan Abed, Chowdhury joined BRAC in 1977, five years after the inception of the largest NGO in the world. In the last four and half decades that followed, he has led numerous BRAC projects and collaborations with local and international partners.

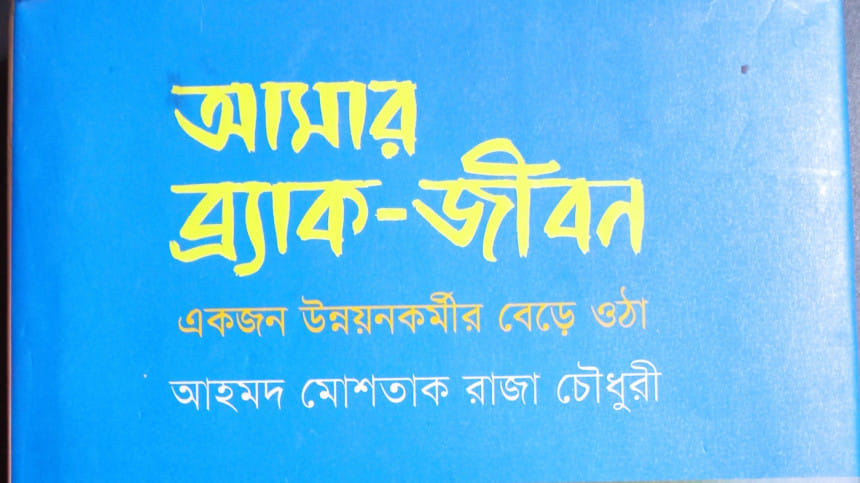

The challenges he faced and how he overcame them have been beautifully narrated in the book, My BRAC Life: The Story of a Development Worker (Prothoma, 2021).

The book depicts how BRAC played a significant role in rebuilding the nation ravaged by the Pakistani occupation forces and their local collaborators during the War of Liberation.

It tells the tales of a dedicated employee, a rarity in this time, but it probably also shows the ability of BRAC and Sir Abed's tendency to make someone feel at home. Time and again he was offered big money deals by international organisations, only for him to turn them down and join BRAC projects that aimed to bring about changes in the lives of the less privileged.

Although the title implies that the book is about the writer's BRAC life, in reality it is more about BRAC and his colleagues and less about the writer. More than discussing his exploits, the writer highlights the contribution of his peers and the role BRAC played in bringing about changes in the rural healthcare ecosystem.

The book is divided into 14 chapters. It begins with the writer's narration of the first one and half years as a BRAC employee, which is followed by his time at the London School of Economics.

Spanning the third and the fourth chapters, the writer talks about how a revolution in the country's public health system took place, thanks to the introduction of oral saline, and covers another significant milestone, respectively, explaining how making 1.6 million pairs of glasses at low cost helped the elderly to keep their work, which was previously threatened because of poor eyesight as they aged.

His and BRAC's collaboration with ICDDR,B and the groundbreaking projects they did together are narrated in the book as well.

The writer led a special issue of Lancet—a noted UK-based journal—on Bangladesh, which he depicted in his book, along with his experiences of working for the Rockefeller Center for four years. Impressed by Thailand's growth and achievement in the development sector, he also keenly points out what BRAC and Bangladesh can learn from the South East Asian nation.

Documenting BRAC's role in the agriculture sector the writer deals with two initiatives, Education Watch and Health Watch.

The thirteenth chapter is the largest in the book—it contains briefs on the research and studies the writer and his teams conducted in his BRAC career. It also sheds light on the foundation of the James P Grant School of Public Health and its scope and promises.

Finally, in a fitting tribute to Sir Abed, Raza Chowdhury seeks to talk about his influence on his work. Three years after the writer joined BRAC, his mentor was bestowed with the prestigious Ramon Magsaysay Award. On receiving the award, the writer recalls Sir Abed saying, "A community of greed has taken over the community of need".

Even after all these years, we have to admit that not much has changed. But whatever change we have seen, that is because of activists like Sir Abed and his able deputy, Ahmad Mustaque Raza Chowdhury.

In the end, the book doesn't only become a memoir of the writer's life as a development worker, but also a tribute to the late Sir Abed and his magnanimity as a human being and a visionary.

We find a man who is a dedicated servant to the biggest NGO in the world—a man with vision who the writer has always tried to emulate and a man who prioritises work more above all else, someone who is ready to forgo millions in order to change the lives of thousands.

The book is a must read for all development workers, seasoned and newbies alike. Not only will this book tell them stories of one of the legends of their sector, but it will also open a new horizon by acquainting the details of the projects the writer and his colleagues have worked on, especially in consideration of the minute details of their work at the grassroots.

Quamrul Hassan is a poet, journalist and translator.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments