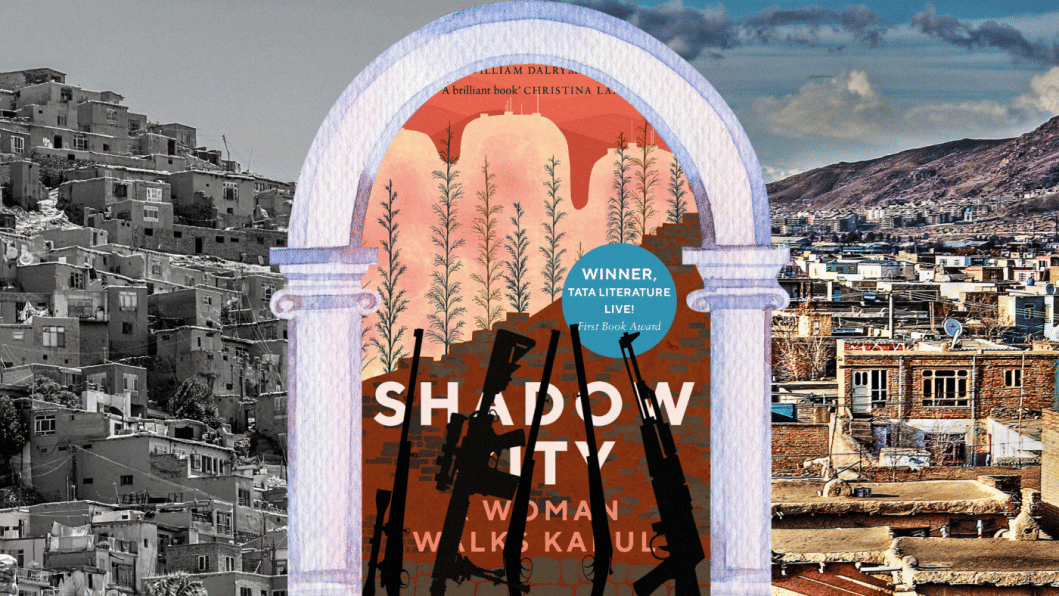

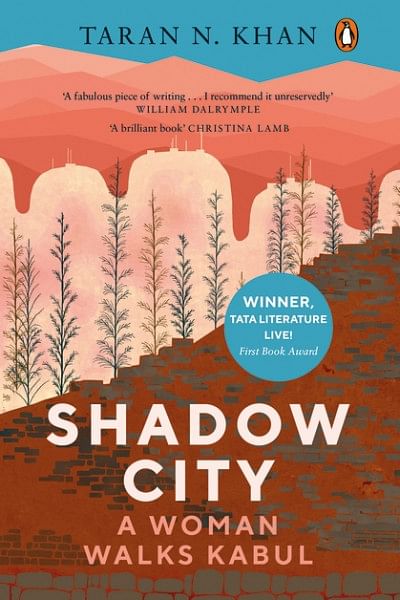

Taran Khan maps Kabul through memory in 'Shadow City'

In 2006, five years after the overthrow of the Taliban in Afghanistan, the Indian journalist and reporter Taran Khan arrives at the nation's capital, Kabul. She is starting at a new job where she is tasked with teaching video editing to Afghan media professionals. Over the course of the next eight years, Khan departs from and returns to Kabul again and again, discovering the city anew each time. In Shadow City: A Woman Walks Kabul (Vintage Books, 2019), Khan delineates a personal map of Kabul, taking the reader through the "shadow city" that can be found in its still-standing monuments, libraries, pleasure gardens, theatres, shopping malls, wedding halls, and graveyards.

In the foreword, Khan tells us that the first instruction she receives after landing in Kabul is "never to walk." As a foreigner, and one that is female, the city is inaccessible to her in more ways than one. However, spurred by a naive optimism and by the echoes of Pashtun lineage in her ancestry, Khan imagines she is "returning" to a lost homeland, so she ignores this dictate, beginning her exploration of the city on foot. She likens her gradual discovery of the space to norms of mystical Persian poetry. Zahir, she tells us, is the overt meaning of a verse, while batin is its concealed, "shadow" meaning. The real Kabul, removed from its long history of war and devastation, lies in its shadows. And as she walks, Khan shows us that all those who occupy Kabul—native Kabulis, expatriates, foreign aid workers, soldiers—have come to inhabit a place that is both there and not there, and one that keeps transforming and growing, but continues to wear its rich history defiantly, if you only know where to look.

On each successive return to the city, Khan always finds it changed beyond recognition. Bombings and evacuations are constantly altering the topography of the metropolis, producing a city spatially defined more by blast walls and security enclosures than the mountains that surround it or the old monuments that lay in ruin near their peaks. By night Khan joins her expatriate friends in parties at upscale homes, and by day she finds herself picking her way carefully through paths laden with active landmines. Khan acknowledges that there is something confusing about Kabul to outsiders, to whom inhabiting such a place must seem inconceivable.

And yet all of the Kabulis she befriends, particularly those who returned to the city after living as refugees in Pakistan and India, are loath to leave the city ever again. Kabul's past is always permeating the present of its dwellers, yet their attachment to the city, despite the country's torrential misfortunes, seems to undercut all natural pessimism.

Part travelogue, part memoir, and part reportage, Shadow City is at once a work of quiet lyricism and unfettered honesty. In many places, it reads like a guided, handheld tour of the uncertain metropolis: a seasoned researcher and incisive analyst, Khan deftly interweaves the city's history into her descriptions of it, allowing the reader to walk with her through an urban space couched in the contradictions of modernity against antiquity and always pulsing with what she terms "violent peace". She does not balk at outlining Kabul's pain as well as its poetry, both of which take on a kaleidoscopic nature. She dedicates entire chapters to the city's artistic legacy and love of revelry while in another, she fleshes out its heartbreaking opium epidemic. In one story that stood out to me, she writes, "At the house, we celebrated birthdays with barbecues, plotted escape routes with the neighbours in case of an ambush, and remembered not to sit down too abruptly on the couch that had the box of grenades under it."

This experience of domesticity in Kabul seems life-affirming in a way only living in a war zone can be. In this way, Khan's prose has a unique precision that, coupled with her natural wit and sometimes wry humor, allows her to tell the story of the shadow city while staying true to her motivations to do so. Khan's personal narrative in Kabul, which depends heavily on her relationship with her late, beloved grandfather, does not overshadow her dedicated depiction of the real stories and lived experiences of Kabulis, but rather exalts them in the author's personal inventory of the batin city. "There have been many books about journalists in war zones, and I didn't feel that was the most important story to be told here. Kabul was the heart of this story," Khan said in an interview. "But it also made sense to use my own vantage point, as a way of making connections and explorations, and also for the reader to understand that this is my perspective. I decided to write about my grandfather because he was so important in the way I explored Kabul."

Most of all, though, Shadow City reveals something about hope, a seemingly impossible condition of living in Kabul. In the first chapter, entitled "Returns," Khan remembers reading of Kabul being described as an "amnesiac city", one whose past, "no matter how glorious… will have left so few reminders, architectural vestiges, and visible traces, that it remains something obscure, if not completely invisible." According to Khan, in this amnesiac city, to walk is a "way to exhume history… as well as [to excavate] the present."

Recalling these lines, as I sift through one analysis after another on what the return of the Taliban means for the country that houses this wondrous city and especially for its women who might no longer possess the agency to walk its streets, I realise a bittersweet truth: the beauty of Kabul is eternally and irrevocably intertwined with its tragedy. Is amnesia not, after all, necessary? Would the Kabulis' rage, and their grief, permit them to continue if they could remember them? Would they want to return, again and again, to a city that is increasingly there and not there? Is love of a place not, in many ways, founded on forgetting?

In 2021, the Taliban have returned to Kabul. Taran Khan, and other foreign workers like her, will likely never revisit the city. Taran Khan's Kabul no longer exists the way she described it, and will no doubt change even further. Like the Buddhas of Bamiyan, many new empty spaces will emerge. But upon reading Shadow City, one remembers not the desolation but rather a constellation of Kabulis who are defined outside of war and even peace, within whom the rich culture and history of the city live on. You will remember Kabul through a kaleidoscope—even if it disappears.

Shehrin Hossain is a graduate of English literature. She can be reached at [email protected].

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments