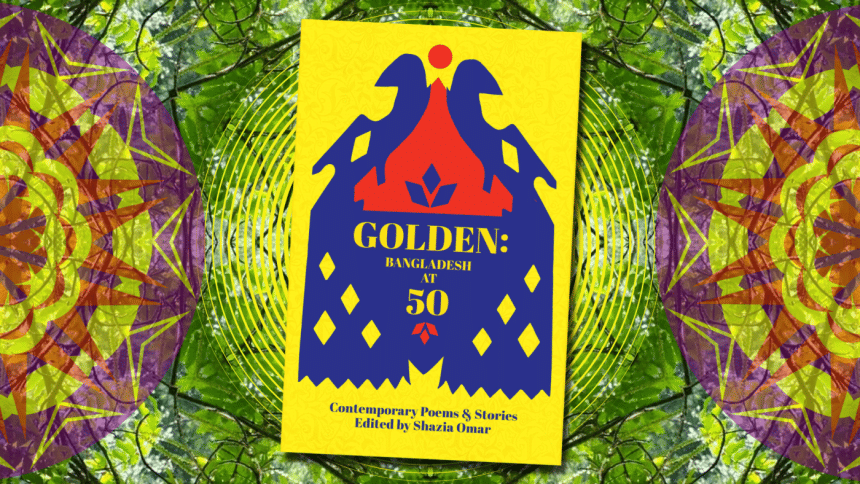

'Golden: Bangladesh at 50' - A tender, discerning look at where we are now

"Who gave you so much independence?"

Early on in the very first story of Golden: Bangladesh at 50 (University Press Limited, 2021), readers of Mahmud Rahman's "The Birthday Cake" are faced with an existential question. Dipika has asked the bakery in New Market to write on her husband Russell's cake in Bangla. But not only have they ignored her request—it's not the way "Happy Birthday is done", after all—but they've also bungled the spelling of his name in English. Russell in Banglish, as we know, is Rasel. Dipika is furious.

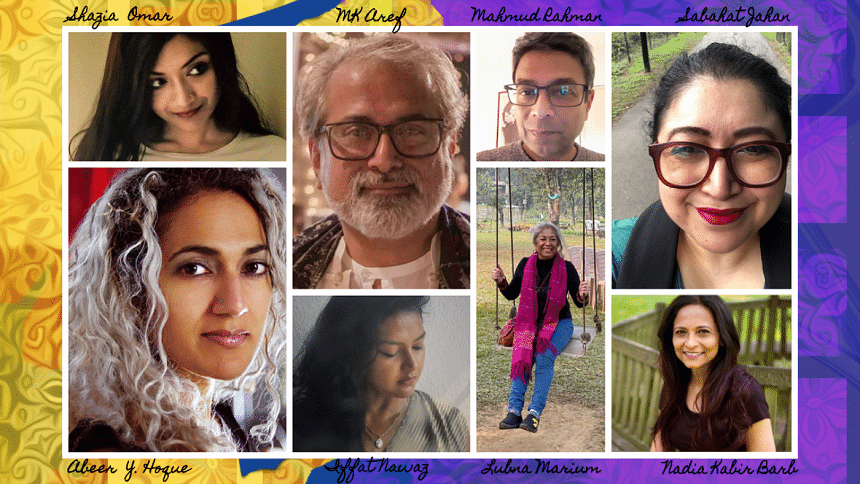

Who did give us so much independence? To us, of this precocious little nation that spills blood to be able to speak in Bangla, that wreaks war to defy unwanted authority, that succumbs to corruption as its overcrowded cities swell with dispassion and inequality, that communicates all of the above in a unique concoction of butchered Bangla, English, and a smattering of other languages? So many wants, so much defiance, so many contradictions in a country so small and so young, yet so vast in its polyphony. While recent anthologies like The Demoness: Best Bangladeshi Stories, 1971-2021 (Aleph Book Company, 2021) have tried to bottle the essence of Bangladesh by offering flashes of its often violent pre-history, this new collection of contemporary Bangladeshi fiction and poetry, edited by Shazia Omar, seems instead to be in a state of introspection. Fifty years old this year, the country represented in Golden is haunted, still, by all that it has survived, and it takes a look at all that it continues to breed, ranging from the festering to the hopeful.

And so it follows that the collection feels wonderfully young, even as it comprises some of the most experienced and eminent of our writers, from Neeman Sobhan and Lubna Marium to Arif Anwar, Nadeem Zaman, Sabrina Ahmad, and many more.

In his "ode on the sari", for instance, poet and academic Kaiser Haq ruminates feverishly on the endlessness of the 18-feet Dhakai muslin, on its tempestuous moods, and on the chaos of the land and climate for which the garment, symbolising the Bangladeshi woman, is far too valuable. Youth filters the gaze through which the characters of Golden look back on independence, on the way this history is taught to children, and the way in which women are "groomed" for adulthood in this country—a culture that has endured from the 1970s, where Maria Chowdhuri's "The Turquoise Necklace" is set, through the decades after independence, when young girls in Farah Ghuznavi's "What My Parents Never Told Me" are punished for reading too liberally or showing disinterest in sewing, right up until the present day, in which a young woman in Salahdin Imam's "Tangled Web" is driven to attempt suicide by the judgments of the marriage market. In one of the most heartbreakingly beautiful additions to the collection, Munize Manzur's "Where Here Is", Mim, once a graduate of Comparative Literature and now a lonely grandmother looked after by the lively young Parul from Gaibanda, goes searching amidst the chaos of a Dhaka city shopping mall to find the place where she had chipped her tooth against the pavement in her youth, when a young love that wasn't to be was meeting its end.

My initial opinion was that the book, as a whole, seems secluded from the experiences of the rural and the extreme poor of Bangladesh, who form our majority. Such characters, when they do appear, do so either in supporting roles—chauffeurs, domestic helpers, rickshaw pullers, beggars—or they appear as flashbacks from a more violent past, as though their struggles were left behind when Bangladesh evolved into a more working class population. The narrators in charge, who enjoy the privilege of intellectual and emotional development over the course of the story, are either from an elite class, or are expats living abroad, or struggling to stay afloat in the urban middle class.

This criticism has more to do with the overall experience of reading the collection, however, which promises a glimpse at the state of Bangladesh in its 50th year, rather than with any of the individual authors, all of whose stories create rich, immersive worlds with a plenitude of compassion. These are also stories that look satirically at all the affluence amassed—wealth, in this book, is portrayed more as a form of pollution than success. They are interested mainly in the kindness and hypocrisy teased out from relationships built across the cultural and socioeconomic spectrum. In the instances in which this filter drops away, Golden is at its purest and most beautiful, as in Pracheta Alam's poems on desh and Shabnam Nadiya's widening of the definition of a freedom fighter.

What I find most admirable about Golden is that it allows us to witness the birth and growth of Bangladesh through intimate moments of kindness, love, and grief. As a result, the book's concerns with the themes of misogyny, dogma, class struggles, and the triumph and trauma of freedom, all of the things that we love and hate about being Bangladeshi, do not come across as boxes to be ticked. At the end of the day, these are stories that one can read to feel moved.

Sarah Anjum Bari is editor of Daily Star Books. Reach her at [email protected] and @wordsinteal on Instagram and Twitter. Golden: Bangladesh at 50 is available for preorder from UPL.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments