The Birangona in fiction: ‘1971’ and ‘Talaash’

When it comes to the representation of the Biragona—the women whom the Pakistan Army raped during Bangladesh's Liberation War of 1971—in the process of retelling history through fiction, not many works can be deemed notable. Birangonas are seldom the subject of an entire literary work on the Liberation War of 1971; their stories are passed on more as a recurring context in which the women are made to be present merely as shadows.

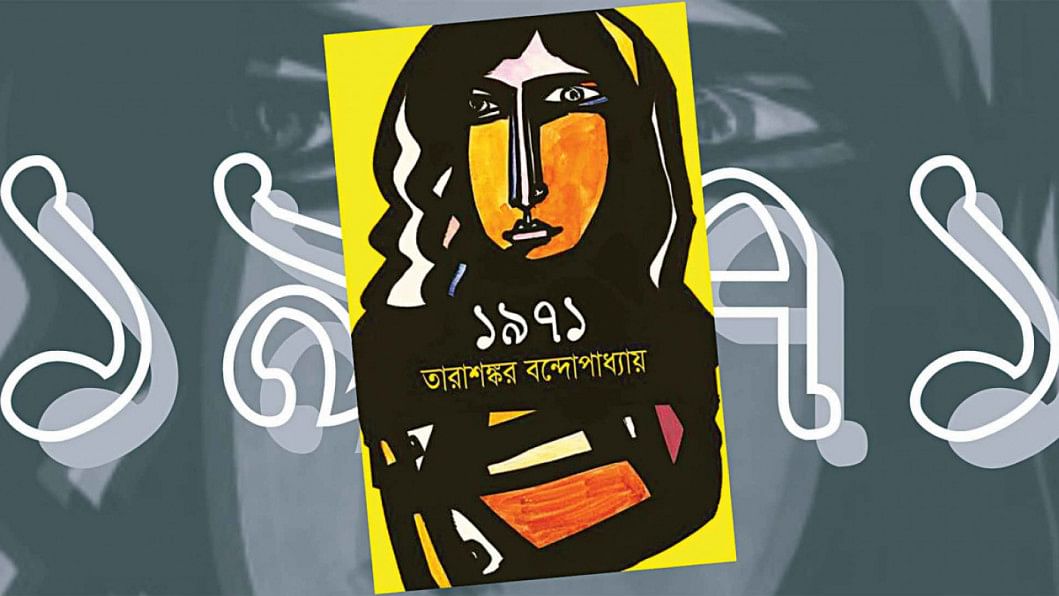

In this addition to this series, following up on the previous instalment's focus on nonfiction narratives of Birangonas's lives and experiences, we recall Tarashankar Bandopadhyay's '1971' (2015) and Shaheen Akhtar's 'Talaash' (2004), two books that can be considered as significant exceptions to the trend mentioned above, and also as examples of the politics of representation, objectification of women, and the desensitisation of lived experiences of trauma.

1971

Tarashankar Bandopadhyay

(Daily Star Books, 2015)

1971 is a compilation of Tarashankar Bandapadhyay's two novellas, "Ekti Kaalo Meyer Golpo"and "Shutpar Tapashya". Tarashankar was as much an activist as he was a novelist, having taken part—and even serving a year in jail for participating—in several anti-fascist movements during his time. In fact, he dropped out of college to join the Non-Cooperation Movement in 1920. His activism clearly informed his writing, and must be the reason why in the months leading up to his death in September, 1971, Tarashankar felt compelled to pen his last two novellas on the politics of the war of independence in Bangladesh.

"Sutopar Tapashya" is told through a series of letters written by a young man, Shubhrot, for his wife, Sutopa. True to Tarashankar's ability to weave current affairs and local contexts into his texts, this correspondence between husband and wife actually serves as an exploration of West Bengal's complex socio-political situation, rife with student protests against the backdrop of the Naxalite revolution.

"Ekti Kaalo Meyer Golpo" is located even closer to home, depicting the life in rural Bangladesh/East Pakistan at the time of our liberation. The story features Nazma, a poor, young girl, who is raped by a Pakistani man.

Though Nazma is the eponymous "kaalo meye" whose story it is, the main character is an odd gentleman named David Armstrong, who would later adopt the more "Muslim" name of Monsur Ali as he settles into life in Pakistan. Armstrong/Ali struggles to cross the border into India during the liberation war, carrying Nazma with him. His distinct Western features land him in the clutches of an Indian inspector who worries he is a spy. The story follows Armstrong/Ali's testimony to prove his innocence, through which he expresses the profound love he has found for Bangladesh and the events that led him to this moment of crossing the border.

Through the subtle narration that is woven between Armstrong's testimony, we know something terrible has happened to Nazma, though the details are unclear. She struggles even to lift herself up to drink water, and is mostly unconscious through the book. As Armstrong begins to talk about the night he escaped from Dhaka, we begin to hear stories of rape.

He tells the inspector how he often came across naked and half-naked women on the streets, trying to hide their bodies however they could. The narration does not shy away from talking about these women, nor does it try to shroud the incident in euphemisms or metaphors. This is important in the light of how Birangonas are often stripped of their own stories. They become dehumanised—their trauma (regardless of whether they are depicted as heroes or victims) become their defining feature. Tarashankar does not try to depict the Birangonas as brave or empowered. Nor does he depict them as purely victims. Through Armstrong, the author provides a harrowingly straightforward depiction instead: that these were women—the few who had been left alive—who are trying to get their bearings after being faced with truly terrible violence.

There is a section in the book in which a Pakistani man named Zafrullah Khan, an old acquaintance of Armstrong's, describes in crude detail the fact that Khan has built a harem of Bangladeshi girls. He goes on to describe that he feels great power when he spends the night with the women in his harem. He says that he feels as though they are prizes he has won in a war. Khan is the man who goes on to rape Nazma. Armstrong describes with horror how he is unable to stop it from happening, how truly grim and dark that moment was.

The fact that this story was written while the war was still on-going, before the term Birangona had been coined, shows how the tales of the atrocities committed by the Pakistan army had been spreading. At a surface level, the story is about Nazma, one of many women who were victims of violence and torture during the war. Nazma is made to represent the fate of millions of young women.

Not only that; Nazma's story reminds us of the meaningless deaths and rapes perpetrated during the war. Nazma was not captured by a soldier, her father and son were not killed in combat. She was raped by a powerful man, confident in his position as a well-to-do Pakistani, who was exploiting the chaos of the war-torn country to sate his carnal appetite. The story reminds us that while the term Birangona tries to add value to the suffering of Bangladeshi women abused during the war, many of these women were not prisoners of war. Rather, they were needlessly abused—often in the "safety" of their own homes.

However, Nazma is also a metaphor for Bangladesh itself. She is often described as strangely beautiful—dark and alluring, with wonderful about her. Just as Nazma carries on after the rape by a vile Pakistani man, despite losing her son, so does Bangladesh, despite the millions of lives that were lost in earning this independence. This use of a woman as a stand-in for the nation is not new or radical, but Tarashankar's simple but evocative way of directly addressing the fact that women are objectified as spoils of the war feels powerful. Partha Chatterjee, Columbia University, wrote of Tarashankar's more famous "Hansuli Baaker Upakatha": "[Tarashankar's] rural novels have found a lasting place in the canon by the sheer density of ethnographic richness and the vivid and earthy realism of his characters." This praise rings true here as well. It is a true testament to Tarashankar's deep understanding of human stories caught in the politics of war that he was able to produce such a seminal story of our independence war while on his deathbed.

TALAASH

Shaheen Akhtar

(Mowla Brother, 2009)

Talaash is a novel based on writer Shaheen Akhtar's own experience in working on an oral history project for Ain o Shalish Kendro, for which she interviewed many war heroines from 1971 and got a firsthand account of their experiences from both during and after the war.

Time becomes multidimensional in this novel, which was translated to English as The Search (Zubaan Books, 2011) by Ella Dutta, and more recently to Korean by South Korean author-translator Seung Hee Jeon, the latter winning Shaheen Akhtar the 3rd Asian Literary Award 2020. The story goes from the time frame of the nine months of the war to the subsequent misfortune faced by these women in the post-war period, with multiple flashbacks, back and forth.

The novel is packed with metaphors, so much that it almost reminds the reader of Salman Rushdie's Midnight's Children (1981), a Partition story in which two children, born at midnight on the eve of India's independence and right after Pakistan's, represent the two countries. In Talaash, the protagonist, Marium, represents the turmoils of Bangladesh as a country, and Mukti, who comes in digging deep into the history of the war, draws a parallel with the country's independence and resembles the character of the novel's author herself.

Shaheen Akhtar also writes of Anuradha Sarker, a well-read, educated young woman who is determined to document the sufferings of women like her in the camps in her own way, drawing inspiration from Anne Frank. During the war, she focuses more on the war at hand that they find themselves faced with—which is the war of survival.

Anuradha's predictions about the war ending and their fates come true in many ways. Their families eagerly await their sons who went to the war, but not the daughters whom the war took against their will, who come back after enduring months of abuse and violence for the same cause. Rather, they are cast out and made to lose the right to self-recognition. Many of them eventually give in to prostitution, as Anuradha predicts. Years later, Anuradha makes a comeback as Radharani, who gave in to prostitution herself after being ostracised by society. As Radharani, Anuradha symbolises own prediction of the fates of women who faced the same traumas as her.

Marium's narration points towards an important observation relating to violence. Every type of physical violence inflicted on these survivors is equally horrifying, according to Marium, who says that people always tend to focus more on the number of times that violence occurred to them and the intensity. "None of it is normal, everything about it is equally horrifying, be that something as simple as a curse word or a slap", she says, indicating the tactic of humiliation used by the members of the Pakistan army and their local collaborators.

Many of these Birangonas come together after many years to share their stories as part of the documentation project that Mukti is working on in the novel. They all portray the lives of outcast women whose lives were engrossed by the deep-rooted patriarchy with an even stronger grip after their sufferings. One thing is certain from their discussions: war makes women more vulnerable than anyone else. With the portrayal of this fact, rendered often through strikingly honest dialogue, and sometimes through monologues, marked by the conflicts and dilemmas around the ways of survival and complex human emotions shaped by trauma, the narrators take a jab at the deep-rooted patriarchy of their society, which they unwillingly have to appease in order to survive.

So heavily packed with metaphors is this novel that it comes across as the most remarkable literary device used in the text. A particular scene from the story comes to my mind, in which the rape survivors are taken to another camp on a truck, without any clothes on them. When the cover of the truck carrying them is somehow lifted by a gust of wind, most of them become self-conscious as people begin to laugh at them. Many even assume that among the men laughing at them from the streets are people that they know, some may even be ex-lovers. This thought, which appears in almost all of the women's minds, lays bare their greater fear of judgment from the ones they know or are close to, rather than from people who are unknown to them. It symbolises strongly the blame and shame that awaits these women after the war is over.

This scene reminds me of something writer Richard Price once said with respect to writing about issues that need to be dealt with sensitivity. "You don't write about the horrors of war. No. You write about a kid's burnt socks lying on the road. You pick the smallest manageable part of the big thing, and you work off the resonance," Price said. That is exactly what these metaphors do in Talaash. They become the way of portraying, with sensitivity, the violence perpetrated against human beings without being violent with them once again. Most importantly, they find a way of empowering these women to break away from the male gaze of the outsider narrative; this gives the women more agency to claim back the right to tell their own stories.

For more book-related news and views, follow Daily Star Books on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, and LinkedIn pages.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments