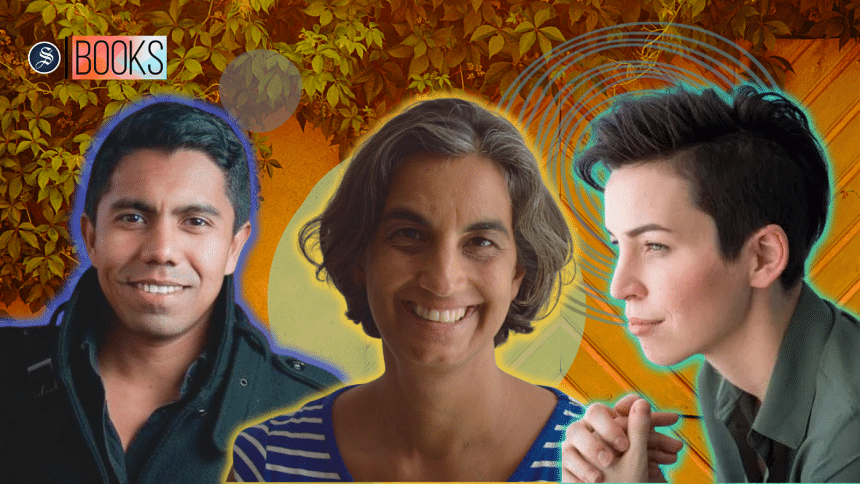

The Hermitage Residency: In Conversation with Arif Anwar and Julia Philips

Last week, Daily Star Books interviewed Bangladeshi-Canadian writer Arif Anwar, author of The Storm (2018), and American novelist Julia Phillips, author of Disappearing Earth (2019). Arif Anwar is the organiser of the annual Hermitage Residency, taking place at Sreemangal from November 14-21. Both Arif Anwar and Julia Phillips will be mentors at this year's residency. In conversation with DS Books sub-editor Amreeta Lethe, the authors discuss details about the residency, the craft of writing, and what it takes to make it as a Bangladeshi writer on the international stage.

Could you start by telling us a bit about your writing process and how that affected your debut novel, Disappearing Earth? Did you mostly follow a routine that helped you finish the book?

Julia: I actually had a routine that was more monthly than daily. I had and still have a writing group that I would meet with, that had monthly deadlines for when we had to turn in chapters — like a story a month. So, every month I had a deadline that I had to write twenty or twenty-five pages. I will say I did that in a very haphazard way. I feel like there are some days where you write a ton and some days or weeks when you don't write at all. It came together that way; it had a rhythm that way.

Do you write short stories? Have you ventured outside the realm of the novel?

Julia: Well, for me, I love the form of the novel — I'm always chasing the form of the novel. I really want to write something that propels you from page one to page three hundred. But I will say, the way Disappearing Earth came together was very short story-esque. I would say it's a novel in stories, where each chapter focuses on a different character. It's daunting to think about it that way, as a book-length work, and it's much more comfortable to go, I'm gonna write these twenty pages, I'm gonna write this one piece, or I'm gonna write this one arc, and then move on to the next. That way you can kind of trick yourself into writing a book-length work.

Arif: I feel like you're downplaying what you did with Disappearing Earth, because it's really hard to keep the narrative thread going with the format that you chose. For a debut author, I would never advise trying something as ambitious as you did. But I didn't follow my own advice, right? The way you keep the narrative thread and the momentum going is really amazing.

Julia: I think that's very kind of you. It's a very generous framing. I love that. But for me, certainly, the first draft is always the hardest part. I like revision quite a bit, I love editing. Just getting those first few pages out is really tough, and I think it's really nice to sort of trick myself into doing it. For me, thinking of it as a collection of separate chapters in the first draft instead of as a whole manuscript helped me trick myself. And then the work became, once I had the first draft, tying it together, creating momentum, creating a through line — and that ended up being much more work than I had chosen to believe while I was tricking myself during writing the first draft.

How much of your novel did you have planned, and how much of it came together later on in your writing journey?

Julia: You know, the answer to both of those questions is "a lot". I had a lot of it planned, and a lot of it came together on the writing journey. This is the first book that I published — Disappearing Earth — but it's not the first manuscript that I wrote. In the manuscript I wrote before it, I had sort of a nebulous idea. If someone asked me what it was about, I would not have been able to answer. I realised after a long, long time of working on it, that that in itself, for me, was a problem: I wasn't arriving, as I wrote, on the answer of what it was about. It kept on being not about anything. I like to read books where I can say that they're about something; I like to read books that have a plot and a propulsive through line. And I want to write books like that. But the process of entirely discovering it along the way wasn't it for me.

So, for Disappearing Earth, when I started it, I wanted to have a very clear idea of what it was about. For me, it's about these two girls who disappear, and this remote community on this Russian peninsula. I wanted it to be about that. I knew what the structure would be — it was going to start with these girls' disappearance; it was going to move over a year in this community's life; each chapter was going to focus on a different woman or girl in these missing girls' community; and it would sort of drive towards a certain end where we would find out what happened.

That said, as I wrote, each chapter offered new discoveries. How they came together was new for me, and even the answer that we would find switched halfway through. So, there was a lot that I found out along the way, but certainly, there was a much more specific idea I had about what it would be going into it, that didn't change so much as I wrote.

Arif: I'd love for Julia to also talk about what's coming next from her.

Julia: Yeah, I have a book coming out next year, which I'm excited about. I had much more of a process for this one. I set up an aim to write 250 words a day minimum, which is not that much; it's one double spaced page. I just wrote that and realised you can bang out a book so fast! I realised how much of my writing process before was procrastinating around writing, and once I did, I felt like I had been waiting my whole life to write a book this way.

It's called Bear, like the animal. It's about a woman trying to keep her sister from getting dangerously close to a grizzly bear. It's like Disappearing Earth, in that it's about two sisters and is set in an isolated place; it has this kind of looming danger that's threatening them, which is very similar to Disappearing Earth. Structurally, it's different, and different in setting since it's in a different country. It's different in scope, and I'm really excited.

Since you had more of a process for this one, did you still end up with an unmanageable first draft that you had to then whittle down?

Julia: Definitely. I had to rewrite it five times afterwards and replot the last two-thirds of it; I started in the right place and went in all the wrong directions. But I like that. The seemingly unmanageable part of it is nice. At this point, I've started to have confidence that I can finish it. Even if I'm totally daunted and don't know where to go, I have by now a few manuscripts and begun to feel like I can figure it out. It might take a year or two or three, but I can figure out how to proceed, which is exciting.

As you start this residency as a mentor, what are you hoping to see in the works of the writers that you'll be mentoring?

Arif: I should clarify that last year, Julia got to read the submissions first. This year, because we're not focusing on novels and most of the writers don't have a big-length work to submit, we're doing more workshops and lectures. So, I don't think the mentors will necessarily be reading big chunks of work by the participants, but instead engage with them and their work in real time while they're there.

Julia: I will say, my expectations are very high. Last year, I got to work with two different folks and their works were wonderful. It was really far-reaching and really educational for me, in the way that great fiction is, where you read it and think, "I never stepped into this person's shoes before. I never knew this person's life. I never thought about what it would be like to be in this situation, and now I am." And that is so illuminating.

I really loved reading both of their works and now I have these high expectations for what I will continue to encounter in this residency again. I don't know what structure or length it would be or what it would be about, but I'm excited and I expect some very great work.

On your end, what ideas are you hoping to touch on during the mentorship period? Since there will be a more lecture-based program this time, what do you want to accomplish through the workshops that you'll be facilitating?

Julia: I always talk about story structure. So, I would love to talk about what our paradigm is about how a story looks, what our expectations are about how a story builds, and then how we upend or subvert that. How do we play with the expectations around momentum and propulsion and page turners? Because I talk about this perpetually, I talk about it with the hope of people engaging in dialogue and a back and forth, of them upending the assumptions that I go in there with — that's what I hope and want to happen, and I would say that's what I expect to happen. I'm really excited for people to push back, ask questions, and have their own ideas of how structure functions.

Even though this iteration of the residency is focusing more on classes and workshops, do you think it's still a co-learning space for the participants and mentors alike?

Arif: Absolutely. I think, when you're together with writers, there's just something in the air. The blocks in your imagination melt away, the fecundity of your imagination increases, and you're just inspired.

We're lonely creatures, right? We're solitary creatures. We're not lions or tigers. We seldom come across each other in the jungle, and when we do, there's excitement — it's a battle. You get together with other writers and you finally have someone you can talk to about the joys and the challenges and the tragedies of the profession. You can't really do that with anyone else. It's hard to find people to connect to, so when you find your tribe — and we rarely do — it's very exciting. That's what I'm hoping for with the residency.

Is there a specific approach or vision behind how these workshops are arranged and how their topics are decided on?

Arif: I just let the mentors lean on their strengths. I teach creative writing, so I would cover things from my own classes about novel writing — point of view, character and dialogue, tension and suspense. There's the craft, and there's the lifestyle. What are the intangibles of being a writer? What are the implications of being a writer? How do you get recognised? So, that part of it, alongside the writing, is going to be touched upon.

We're very lucky to have Anjali Singh, who was a famous editor before she became an agent. She's the one who discovered Persepolis and championed it. She's also Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie's editor. She has a tremendous wealth of experience from both the publishing side and agents' side. So, each mentor is going to be leaning on their experience. Julia has the experience of being a first-time novelist, and being a super successful one at that.

Most of the students this time are going to be from Bangladesh. Going into international publishing as a Bangladeshi writer, how do you present yourself? Who do you speak to in terms of your audience? How do you speak to them about Bangladesh? What do you explain, what do you unexplain about your culture? All these intangibles that are there about the publishing world, we're going to touch on that. It's going to be sort of haphazard, but it's going to be fun.

What are you hoping the writers will have achieved by the end of the residency?

Arif: I don't necessarily want this to be achievement-oriented, but I do want everyone to leave inspired. And with sort of a momentum that takes them, in some say, beyond the residency to finishing what they want to finish and to form the connections. Networking is another part of it. We have a student flying in all the way from Australia this time. I had interest from someone in Nagaland in northeast India. They wanted to come but couldn't make it because we couldn't provide them with a travel stipend. There's just not enough money, unfortunately. Maybe next year.

But yes, I hope everyone leaves with that bond and connection that they have with other writers. Again, it's a lonely world, and the more people you keep, the more you know. To sum it up, I just want people to leave with momentum.

Julia: I agree with that wholeheartedly. Just to echo what you said, I do think that the task I have as a mentor, a writer, a person in the world, is to stoke that fire that's inside people. Each of us has such creative passion within us, and I think it's really important that we help them cultivate that fire and stoke it as it grows stronger and stronger. If folks leave more connected to the work they want to do and are more passionate about doing that work, more excited about doing it — that is exactly how it should be.

Could you perhaps talk a little about the construct of the "writing workshop" itself. To explain, while enrollment in humanities is in decline, interest in creative writing programs/workshops is quite high. Why do you think that is?

Arif: I think it's just that now there are so many platforms in which you can get published. So, more people now think that they can express themselves in that way and get their work out in front of a larger audience. Maybe that's why. I think it's also the idea of writer as celebrity, which I think, as I was growing up, didn't exist to the same extent. You just read the book and didn't think too much about the writer. That separation of the story and the writer, I think there's less and less of that now. The idea of the celebrity writer — maybe some people want a part of that, which is unlikely for many of us to achieve. So, maybe there's that glamour in being a writer, and maybe that's what people are seeking. Maybe that's why the interest has not died as much.

The relationships between celebrity writers and the audiences or readers are egged on nowadays by social media and parasocial relationships. The publishing world has certainly not been spared from that. What do you think about writing becoming "content"?

Julia: What you're saying is really relevant. Do you ever read those articles about how everyone in Iceland is a novelist? Like one in every four Icelandic people publish a novel. Everyone in Iceland is writing novels, and there aren't that many people there, and they just all write novels.

Arif: So, all five of them?

Julia: Yeah, pretty much. They just love writing books there, and the reason I think of it now is because I think storytelling is a very human thing. People tell stories, it's what we do. We tell stories that we make up stories about our own lives, why people do things they do, why the person we went on a date with didn't call us back, why our mom is so mean to us…we tell stories, that's what we do. And writing those stories down has a very low barrier to entry. You don't have to buy paint or clay or go to a dance studio. You just do it. It's a very simple thing to do to start typing something. It doesn't take a lot of preparation, and you don't have to stretch beforehand.

I think people tell stories, and I think they can easily transition into writing those stories down. A lot of people — all of us, not just Icelandic people — have something to say. We have something we want to tell other people. It's not just the feeling of telling stories that's nice, it's also the feeling of telling stories to someone, the feeling of giving someone else your story to listen to. Writing workshops, programs, or just writing communities in general, create spaces to honour, indulge, or cultivate those natural tendencies. People want to say something to each other, and here is a place where you can.

As an asterisk to what I said, when it comes to content, I think different people feel different ways about different social media platforms. I will say, in my life, I have not yet found a social media platform that made me think, "Wow, this is a natural and appropriate fit for the way that we want to express ourselves." They seem quite reductive. But that said, I'm not a flash writer and not a poet, and perhaps the short form, which is as yet unexplored to me, has great potential for expressing the stories we have inside.

What advice for writers who are dealing with that process of having completed their first draft and trying to figure out the way forward?

Julia: I think that once you have it, giving it some time is a great idea. Sharing it with a trusted reader who can offer feedback can be great, like a workshop group or a writing group. Reading the books that you put off reading because you knew that they were going to be great source material but you didn't want to read them because they were too close to what you would be writing — you can read those then. And just keep the faith.

Whenever I'm working on a project, I want so bad to finish it. The middle feels like it takes forever, an interminable middle, and the ending keeps getting farther and farther away. It feels awful. But it is a real practice to repeat to oneself, "This is actually the good part. This is the fun part. This is the interesting part. I know it feels uncomfortable, but I don't have to rush in to finish it. I don't have to rush it out to the world. In fact, taking time is going to be the best possible way I can serve the story I'm trying to tell. It takes the time that it takes, and that's great."

The book that's coming out is the fourth manuscript I've written. It'll be the second novel I'll publish. That's very lucky; it's a great rate of return. And I'm really glad I've written those four manuscripts. I'm really glad that I didn't just write the two that got published. It's a very winding path within each book and within our careers, but it's a good one. So, as much as we can, we should enjoy the journey. And if you have to have your first draft put in a drawer, have it sit for several months, and then pick it back up, that's fine.

Amreeta Lethe is a Sub editor at Star Books and Literature and the Editor-in-Chief at The Dhaka Apologue. Find them @lethean._ on Instagram.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments