The stories that nonfictions tell

Dense textbooks with words more twisted than the shapes my lips could contort themselves into—for the longest time, my perception of non-fiction didn't deviate from this singular image. Perhaps it was the uncanny resemblance to textbooks or the ruthless objectivity these books claimed that deterred me from picking up non-fiction. Or perhaps it was because my brain had become wired in a way that I perceived everything that was not immersive fiction to be monotonous and cold.

A fiction reader by nature, I had trained my overactive imagination to find comfort in fantastical worlds. It was in the iciness of a Fjerdan jail and in the bittersweet warmth of District 12 that I found my home. The pedestal on which I placed my perception of fiction made it all the more hard for non-fiction to climb its way to my good graces. Even the idea of reading something rooted in reality felt tedious to me. That is until I read Muhammad Zafar Iqbal's Obisshassho Shundor Prithibi (Kakoli Prokashoni, 2019).

Iqbal's fiction books hadn't really captivated me. Thus, it was with little expectation that I turned the cover of my mother's copy of the pocket-sized, blue book. Chronicling the emotions he experienced after being physically attacked by a student in 2018 and written in astoundingly simple prose, the book felt hauntingly vulnerable. Here was a book, clearly based on real events, that I had come to love. I realised that I was wrong to label non-fiction as cold. Yes, the genre certainly has the capacity to be disconnected from feelings. However, the book made me see how non-fiction can be artfully crafted to portray factual happenings in an almost lyrical fashion. The book could easily have been a drab chronological account; but, with the right literary tools, it morphed into the painful, hopeful, and beautiful musings of a wounded man trying to find his path toward physical and emotional recovery.

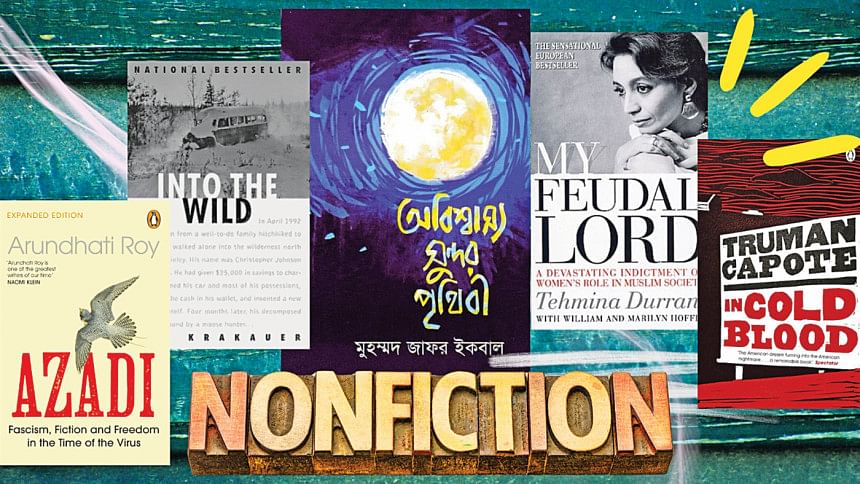

To label this incident as a turning point in my reading journey would be inaccurate. It was not a religious experience; it did not suddenly convert me into an avid reader of nonfiction. But it opened me to the possibility of exploring the world of nonfiction. I started small, dipping my toes into creative nonfiction. I had just watched a rerun of Sean Penn's Into the Wild on HBO and decided to pick up Jon Krakauer's book of the same name. Packed with multiple threads, some weaving through the story of a young man's search for himself and others going into dense tangents on literary analogies, the book was not an easy read. But I also couldn't put it down. The narrative was tied together with the small personal tidbits the author provided, paralleling their own experiences with that of the subject, and that furnished the book with a strong human touch that made it hard to not keep turning the pages.

Having finally found the brand of nonfiction that I connected with—creative nonfiction or simply any nonfiction with a strong sense of personality—I finally plucked up the courage to dive deeper into this unknown realm. In Truman Capote's In Cold Blood (Random House, 1966), I discovered the thrill of reading true crime. By laying bare both the gruesome and mundane details of the lives of the victims and perpetrators within the scope of 300 pages, the book expanded my understanding of how horror and tragedy can be crafted into a piece of art. With Tehmina Durrani's My Feudal Lord (Corgi Books, 1996), I saw how a person can channel their anger and frustration to create writing that is devastatingly moving.

As a reader, I shouldn't be burdened with the responsibility of reading anything and everything. To do so would be to make the act of reading a chore. It's hard enough to find a rhythm in a genre that is out of my comfort zone. Thus, I would rather take my time with it, punctuating the experience with easy fiction reads in between.

I see now too, unlike textbooks, I don't need to necessarily remember all the details of the book. A piece of work being filled with information alludes to the idea of needing to retain that information because it resembles academic text. I had to shed this idea, reminding myself that, unlike academic text, there are no consequences if I don't remember the nitty-gritty of Arundhati Roy's political inclinations in Azadi (Penguin Random House India, 2020). I simply need to retain the passion behind her prose and the strength of the feelings I experienced while consuming her words.

I think the main barrier I had with nonfiction was separating it so severely from fiction. Creating that mental hurdle for myself kept me away from giving a whole area of literature a shot. What I should have done from the very beginning was to find the overarching story in every book. I regret not starting with nonfiction sooner, but I am trying to rectify my bias with every new fact-filled tome I read.

Adrita Zaima Islam is a struggling student and writer, and she is trying her best to be the best version of herself. Send her your condolences at [email protected].

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments