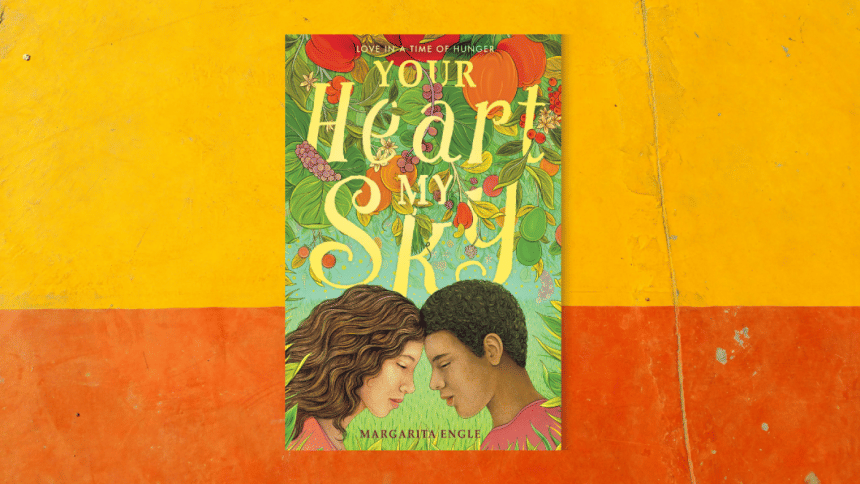

'Your Heart, My Sky': A timely YA novel-in-verse about the 1990s Cuban “Special Period”

Early in July of this year, thousands of Cubans took to the streets of the country's major and minor cities, pushed over the course of the pandemic to a breaking point by a persistent, two-year-long shortage of medicine and—perhaps more importantly—food. The Cuban protesters marched and shouted for an end to the Communist regime, which has lasted for over six decades since the Cuban Revolution, famously headed by Fidel Castro and Che Guevara. To many of the older protesters, one of the worst possible outcomes of this continuing scarcity might be a repeat of the periodo especial en tiempos de paz, the Cuban "special period in times of peace," which had lasted from 1991 to 2000.

This Special Period is the centerpiece around which Cuban-American author Margarita Engle's verse novel Your Heart, My Sky (Simon & Schuster, 2021) revolves. It's the summer of 1991, and Cuba is facing a crisis of widespread food shortage and poverty. The protagonists are starving teenagers Liana and Amado, who inhabit the picturesque town of Trinidad, alienated from the capital Havana where, somewhat ridiculously, the 1991 Pan-American Games are being hosted. While the tourists attracted by the Games are feasted like kings, common Cubans are restricted to rations which are meagre at best and imaginary at worst. They are also, inconceivably, prohibited from farming their own land or even leaving the country. The average Cuban family is, therefore, left with a few bleak choices: continue to starve, risk imprisonment for illegally growing their own food, or become one of the thousands of balseros, refugees fleeing on precarious self-constructed rafts to the East Coast of America. Castro's government insists that all this is merely part of a "special period" during which Cubans must gather all their nationalistic pride and make the sacrifices required to sustain the regime.

At the start of the story, Liana and Amado are strangers, but are both guilty of being truants from la escuela al campo, the "voluntary" farm labour programme sanctioned by the government for teenagers all over Cuba. The two teenagers are brought together when a "singing dog" befriended by Liana begins to play the role of a mythical matchmaker. Accompanied by their canine companion and their ever-present hunger, the two roam all over town in search of sustenance on streets and gardens and beaches. They slowly fall in love even as they search for uncanny but indispensable sources of protein, considering themselves lucky to find anything like "a discarded fish head, / plump tree rat, / or jumping bullfrog."

Although the plot moves in fits and starts and falls short of being wholly satisfying, that seems to mirror the halting uncertainty of being a Cuban during the country's Special Period. In turn, this reflects the impeded development of Cuba itself, left in the lurch by the dissolution of the Soviet Union and weighed down further by a brutal American trade embargo (which, of course, persists to this day). The "singing dog," fashioned on a breed of legendary, fox-like Cuban canines of old, brings a thoughtful, albeit underdeveloped, touch of magical realism.

However, what feels refreshing about this novel-in-verse is the lack of sickly-sweet wish fulfilment that would have drowned a lesser young adult novel. Engle's verse is gentle and luminous, handling softly the vulnerability that attends any adolescent experience. But the viscerality of starvation is no less pronounced, and neither are the tyrannies of the "bearded man's" regime that the common people of Cuba have come to accept as the norm. Aching with hunger, Amado and Liana "gobble odd-shaped creatures raw" they find near the beach, with no mind to pay to the "natural expanse of beauty" that "does not seem to belong to the same world / as starvation." Amado discovers that his "rugged, cigar-smoking" abuela has nearly gone blind from malnutrition. When a tourist from Havana comes to Trinidad to find better waves to surf, the reader discovers that Cubans are not allowed to interact with the tourist (and in fact, Cuba's "tourism apartheid" was still in place until only a decade ago). Amado's brother, a dissident against the regime, rots in prison. And all the while, the possibility of escaping the island via raft looms over the ocean horizon, tempting yet dread-inducing.

Poignancy is perhaps easy to achieve in a work with such potent themes—those of love and starvation—set against a nationwide humanitarian crisis. But it's Engle's use of free verse that makes this such a special novel. Be it the absurdity of state-sanctioned starvation, the serendipitous magic of a matchmaking dog, or the cruelty of forced farm labour (being absent from which marks the teenagers for future punishment by purposely barring them from professional and academic opportunities), the altering cadences of Engle's free-verse poetry do it justice. Especially when read out loud—as all verse should be—Engle's efforts to spotlight the story of Cuba's ongoing travails for young readers assume a nobility not easily felt in the unimaginative conventions of mainstream YA novels in prose.

In Your Heart, My Sky, as in many of her other novels written for young people, Engle makes accessible to the reader an important part of Cuba's history that is, in many ways, repeating itself. She situates the soft splendour of adolescent love right beside gnawing hunger in two growing bodies. And in doing so, she succeeds in relaying the struggle of a people who are still, decades later, trying to find something to eat.

Shehrin Hossain is a graduate of English literature. She can be reached at [email protected].

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments