Voices of resistance: Stories of women’s struggles and resilience in South Asia

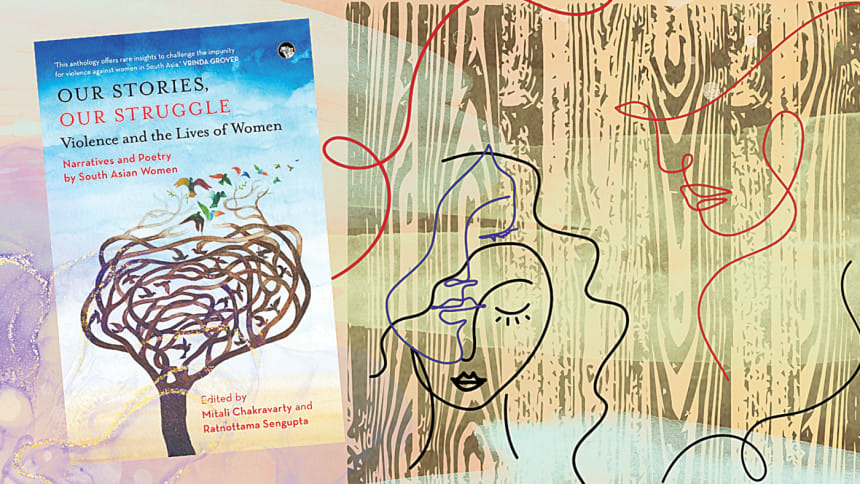

Our Stories, Our Struggles: Violence and the Lives of Women (Speaking Tiger Books, 2024) is an anthology edited by Mitali Chakravarty and Ratnottama Sengupta. A mix of nonfiction, including 20 personal narratives and analytical essays, 10 fictional stories and six poems, the book focuses upon the plight of women in South Asian countries and delves deep into the pervasive issue of violence, exploring its many faces across borders; it calls to the survivors to rise above victimhood.

Contributors to the collection not only question and bring to focus the issues like rape, acid attacks, dowry deaths, and honour killings, but also celebrate the resilience of women and their defiance in the face of suppression and subsequent challenges. The anthology draws upon real-life events, including the pivotal Nirbhaya case, to examine systemic failures and the cultural shifts needed to empower survivors. As Mitali Chakravarty writes in the preface, there is a necessity of "integrating women in the mainstream of humanity, historically dominated by men in South Asian social framework".

The contributors, writing from India, Pakistan, Nepal, Sri Lanka and Bangladesh, bring voices reverberating with concerns alike in implications that necessitate urgent attention. Meenakshi Malhotra's essay on Nirbhaya is a profound study of the societal dynamics, the transformative role of media and public outrage in challenging injustice whereas Kalpana Kannabiran's essay questions a different facet of "pervasive majoritarian misogyny" where public and media outrage seems to be absent when it comes to victims of sexual assault from minority, dalit, or indigenous backgrounds. The perpetrators of crime, unlike in the case of Nirbhaya or Dr Priyanka Reddy, come with a political clout and are guaranteed impunity like in the Hathras case, in the case of women wrestlers protesting at Jantar Mantar or in the case of Bilkis Bano. In such cases, what does the stand of those upholders of "justice" signify? Where can the victims go if the keepers of rule of law and justice betray them? In the introduction to the anthology, Subhashini Ali echoes this concern by asking to speak and resist in the face of a pushback to women's fight in the last decade by right wing forces "which enjoy a kind of impunity that is both new and terrifying" whether it be the case of women from minority background or of Manipuri women suffering continuous violence in the wake of recent civil unrest.

Sohana Manzoor's poignant narrative from Bangladesh casts light on the mindset of society which not only dehumanises a teenage victim, raped and burned and killed, but also slaughters her dignity by holding her responsible for the assault on her. The moving narrative by Eli Prue Marma focuses upon the harrowing rapes and murders of indigenous women of Chittagong Hill tracts in Bangladesh where the perpetrators of crime usually escape punishment for the supposed lack of evidence.

The threat of violence against women is glaringly evident both outside and inside the confines of their homes. One of Ratnottama Sengupta's three essays in the collection is centered upon the threat of acid attacks upon women while the other ones are on the threat of killing by one's family whether in the garb of honour killing or the abolished sati pratha. The Late Sandhya Sinha's narrative translated from Bangla by Sengupta is a heart wrenching cry for the 18-year-old Roop Kanwar who was sent to the pyre with her dead husband in 1987 while the perpetrators of the ghastly act went unpunished. This narrative is especially significant as the eight perpetrators who were arrested earlier were freed in October 2024.

Each and every piece of writing in this anthology stands out for poignantly portraying the intersections of deep-seated norms for women in a patriarchal society that pose quagmires women are coerced to navigate. Their predicament, when violence in any form is committed against them, is not only that their bodies are violated but it is also their dignity that is crushed. Babita Basnet's article reverberates with concerns about the issue of women trafficking in Nepal whereas Farah Ahmed's narrative gives a peek into the plight of women from minority communities in the prisons of Pakistan.

In patriarchal societies women are expected to compromise their well-being and happiness for the sake of their families even if they endure suffering at their hands. Nishi Pulugurtha's real life narrative points to the despair and helplessness a woman struggles with, going into severe depression yet continuing to live with her oppressive husband because she has no power to come out of it. Another woman from an unprivileged background in neighbouring Pakistan gets university education despite all odds and tries to live a better life but is consistently reminded that women are "charpais". Selma Tufail's narrative focuses upon the subjugation of women in a society where her fate is decided by the all-male "jirga" (similar to Khaap panchayats in India).

However, when a woman decides to defy the forced conventions, we come across brave stories like Ankita Banerjee's first-hand narrative of sexual abuse, which exposes uncomfortable truths and compels families to face them.

The fictive narratives from all five countries reverberate with similar urgency and concerns that are echoed in the essays and real-life narratives. Imagined women from different backgrounds trying to claim their voices, their agencies, their basic rights and are crushed, trampled upon, killed, raped, or abused for just expecting that. A girl child, a young woman or an older one, her body, mind, and soul bear the brunt of violence because she is an easy target. In Aruna Chakravarty's heart-rending story, an old, lonely and starving woman is burnt as a witch whereas her granddaughter suffers incest. Radhia Rameez's two stories set in Sri Lanka deal with the subject of marital violence where the doors to freedom from brutality remain perpetually closed to women. More stories from Bangladesh, Nepal, and Pakistan expose brutalities at different levels. S. Bari's story is remarkable in bringing hope when she showcases a rape survivor outgrow her victimhood.

The poetry section starts with, Arundhati Subramaniam's poem "Claim", which iterates:

"We are here to restore order,

to put the voices–of books, lovers,

teachers, customs, officials–

in their place"

Additionally, Sadaf Saaz takes up the plight of the war widows of Bangladesh, the Birangonas, and like an afterword,

Mitali Chakravarty's "Amphan Calls" summons courage:

"Was Amphan–the invisible energy–a Woman?

Did She rage for you and me tearing, searing with madness

for the unspoken wounds which can only heal with phoenix eardrops?

Rise, rise up to Amphan's call–with our souls, let us conquer all."

The blend of personal experiences and broader cultural critiques makes this anthology a powerful resource for understanding gender-based violence in the region. Equally compelling are the stories and verses in the anthology which augment the call for resilience. The volume transcends victimhood narratives, showcasing the courage and agency of women who challenge patriarchal norms. It is not just a documentation of injustices but a clarion call for justice and equality. A call for systematic reforms. A call to reclaim agency.

Rakhi Dalal is an educator. Her writing has appeared in Kitaab, Scroll, and Borderless Journal, among others. Her essay on Partition, invited by Bound India, made it to the list of winning pieces.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments