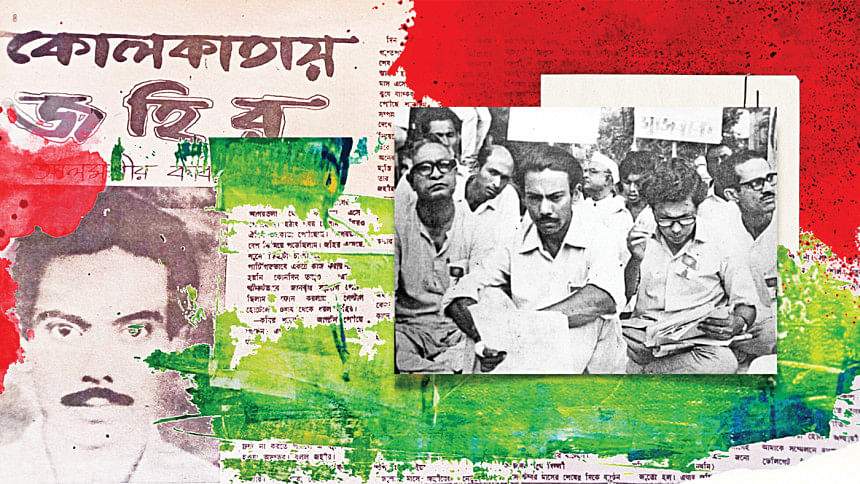

Alamgir Kabir: “Zahir in Kolkata”

In memory of the events of March 1971, when Bangladesh was taking up arms to fight for liberation, we translate and reprint part of an article written by Bangladeshi film director and cultural activist, Alamgir Kabir. Originally published in the Weekly Chitrali on February 2, 1973, Kabir, in this article, writes of his experiences working with novelist, writer, and filmmaker, Zahir Raihan in 1971, and of the conception of a historic film on Bangladesh's liberation struggle.

17 April, 1971. I reached Kolkata from Agartala on the previous day. Word reaches me that Zahir Raihan has also arrived at Kolkata on the same day. I had grown quite bored in Agartala. The news of Zahir's arrival gave me renewed energy. We had never worked together as a party, but I had gotten the chance to get to know him closely while working in the 'Express'. I placed a call to Central Hotel. Zahir's voice came through.

—Kabir, I hear you've reached. Please come over right away. There is something we need to discuss.

His voice brims with excitement.

We meet up. It takes us about half an hour to set up a plan. Progressives have to be organised to cooperate with the provisional government.

—But what if the government doesn't want our help? I ask.

—Then we have to force them. This war cannot be won without the formation of the National Front, Zahir says. His voice carries that ever-familiar cadence of confidence. We begin working.

I take a secret path and return to Dhaka in a few days for a special assignment, towards the end of April. By my own negligence, which brings me injuries, it is June by the time I can leave Dhaka again. A long, winding path through Bangkok finally lands me back in Kolkata on June 6. Upon reaching, I hear that my funeral has already been performed. Given the delay of my arrival, Zahir and other friends had assumed that the Pakistanis had killed me off. Significant amount of work is under way in Kolkata by then. Buddhijibi Mukti Parishad has been formed. Zahir is its general secretary. I join in.

Zahir is insulted

I had heard Zahir's voice on the Bangladesh Radio while in Dhaka. In his strong, loud voice, he had been criticising Pakistani demonism. Upon reaching Kolkata and, upon the government's orders, taking up responsibility of Shwadhin Betar's English wing, I found out from the recording station that Zahir Raihan was no longer participating in the radio. Why? No one seemed to know. I asked the authorities why Zahir's powerful writing was not being put to use. I found no answers. I insisted on Zahir and finally found out. The authorities had requested Zahir to write a short piece on the history of Bangladesh's Liberation Movement. He had spent 4-5 strenuous days on the submission. But one of the influential leaders did not like what he had written. That valuable document was not transmitted, and since then Zahir Raihan had not set foot around the radio station. Until the very end.

Stop Genocide

Bangladesh Chalachitra Shilpi-O-Kushali Swahayak Samity was formed in July, led and presided over by Zahir Raihan and under the tireless work of Hasan Imam. The Eastern India Motion Pictures Association (EIMPA), Kolkata, by setting up monthly payments, had sought to lessen the struggles of the family members of film workers in exile. EIMPA ardently requested Zahir Raihan to make a film.

Zahir rediscovered, suddenly, his infinite energy. Work began and took over our days and nights—shooting, editing, narration, recording. At home his wife, Shuchonda, lay unconscious with fever. There was no one around to take care of Opu and Topu. But Zahir was unstoppable. Utterly free in the joys of creation. After six weeks of near-inhumane hard work—neither Zahir nor his co-workers took a single penny for this film—Stop Genocide was completed. Word spread around the studio neighbourhood in Kolkata. Critics came to watch the film in droves. They were stunned at the talent showcased by this small, slender man of 5' 3 inches.

Shortly before Stop Genocide was made, the Bangladesh Chalachitra Shilpi-O-Kushali Swahayak Samity, with Zahir Raihan's encouragement and Wahidul Haque's tireless dedication, created a lyrical composition in tribute to Bangladesh's movement for freedom. From these lyrics arose a new group of musicians who still prevail, who are still touring and performing across the lands of a liberated Bengal in various modes.

Translated from Bangla by Sarah Anjum Bari and Maisha Syeda.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments