Bangladesh, often described as a land of rivers, is criss-crossed by more than 230 major and minor waterways. These freshwater lifelines are vital to the country's survival — fuelling agriculture, sustaining fisheries, supporting domestic needs, and powering industrial activities. But the very arteries that once nurtured its economy and ecosystems are now under siege. While most of the pollution choking Dhaka's rivers is driven by human activity, it doesn't stop there. Shifting hydrological patterns, agricultural runoff, climate change, and erratic rainfall are all compounding the damage.

Rapid industrialisation — particularly in booming sectors like textiles, tanneries, pharmaceuticals, and ship-breaking — is placing immense strain on these rivers. Urbanisation in Bangladesh is also accelerating at a pace the landscape can barely withstand—often with little to no regard for environmental sustainability. The unchecked discharge of industrial effluents and municipal wastewater into river systems is introducing a cocktail of pollutants: heavy metals, dyes, acids, alkalis, and organic waste.

Yet, despite growing alarm, research has failed to keep up. Only a handful of studies have examined how rapid urban growth and unplanned industrialisation are reshaping the long-term water quality of the city's rivers. And without a clear understanding of the scale and causes of the crisis, any hope for sustainable water management remains out of reach.

To grasp the full extent of this crisis, Dhaka's peripheral rivers offer a revealing case in point. The Buriganga, Turag, Shitalakshya, and Balu rivers illustrate how unchecked industrial growth and poor planning are pushing urban waterways to the brink. The culprits are well known: industries producing soap, detergents, garments, pharmaceuticals, tanneries, dyes, aluminium, batteries, pulp and paper, and a range of chemicals. Many of these factories discharge untreated effluents directly into the rivers, contaminating the surface water with a dangerous mix of pollutants.

Every day, 60,000 cubic metres of hazardous liquid waste is discharged into the Buriganga River, which flows past Dhaka city and connects the Turag, Tongi Canal, Balu, Shitalakshya, and Dhaleshwari rivers. In addition, every day, one and a half million cubic metres of waste from industries along the river are discharged into the rivers around Dhaka. The majority of this waste is generated in the Dhaka Export Processing Zone (DEPZ), Narayanganj, Tongi, Hazaribagh, Tejgaon, Savar, Gazipur, and Ghorashal, which are major industrial areas.

Before being shifted to Savar Upazila, 15,000 tonnes of liquid waste, 19,000 kg of solid waste, and 17,600 kg of biodegradable waste were discharged into the Buriganga River from tanneries in Hazaribagh and Rayer Bazar in Dhaka every day.

In addition, Dhaka's large population produces a significant amount of household waste daily. A large portion of this waste is dumped directly into the river. Due to the lack of a sewage system and an unplanned drainage system in the city, dirt and garbage end up in the river.

Plastic bags, bottles, and other solid waste used in different parts of the city are thrown into the river. Plastic waste disrupts the normal flow of river water and accumulates on the river bottom, reducing the depth of the river. Dhaka's rivers are used for navigation. Oil and other chemicals released from these vessels mix with the river, further polluting the water.

In addition, chemicals used during ship construction and repair are also harmful to the river. Due to illegal construction and the filling of rivers, the width of the rivers is decreasing, and this is further increasing water pollution.

A study conducted by the Hydrobiogeochemistry and Pollution Control Laboratory of Jahangirnagar University has revealed a picture of rapid urbanisation and its impact on the current state of water quality in rivers around Dhaka.

Dissolved oxygen is one of the most important parameters of water quality, and aquatic organisms, including fish, need sufficient dissolved oxygen to survive. Low dissolved oxygen concentration is dangerous and deadly for aquatic life.

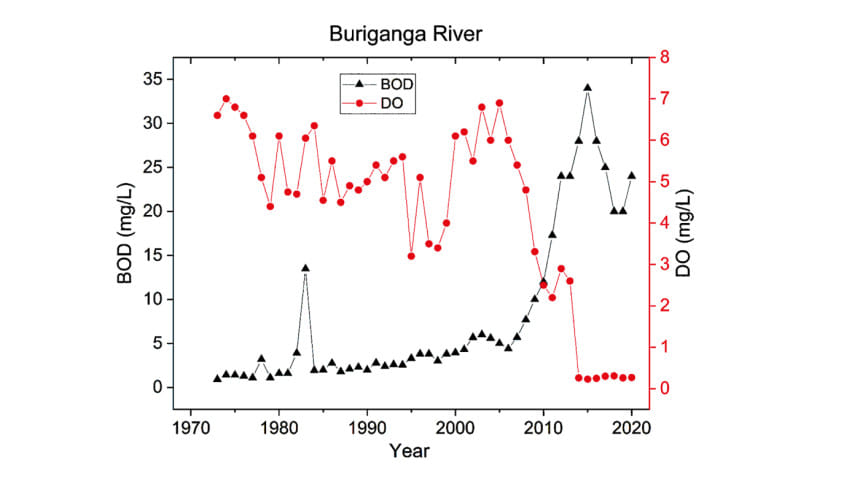

Dissolved oxygen has been decreasing over time from 1973 to 2020. In the 1970s, the average dissolved oxygen concentration of the Buriganga River was more than 6 mg/litre, and until 2005 the concentration varied seasonally. However, after 2005, it decreased rapidly, and in 2015 it reached almost zero—far below the recommended value of the Department of Environment.

The Turag River follows a similar trend. Its initial dissolved oxygen concentration was around 6 mg/litre but has decreased since 2003, reaching almost zero in 2011.

Likewise, the dissolved oxygen concentration in the Shitalakshya River was initially 6 mg/litre on average, like the other two rivers, but has been declining since 1994 and reached nearly zero in 2006.

According to a recent study, the pollution levels of rivers around Dhaka are higher than those of other rivers in the world, as well as other rivers in Bangladesh.

The dissolved oxygen level in the water of rivers around Dhaka is generally 1.5–3.5 mg/litre, which is very dangerous for aquatic organisms. By contrast, the dissolved oxygen level in rivers elsewhere in Bangladesh—such as the Meghna, Jamuna, and Padma—is 5–8 mg/litre, which is relatively good. The cleanest rivers in the world—such as the Amazon, Thames, and Danube—generally have dissolved oxygen levels between 7 and 10 mg/litre.

The BOD (biochemical oxygen demand) of rivers around Dhaka is generally 20–80 mg/litre (higher in the dry season), which indicates serious pollution. In comparison, the BOD of other rivers in Bangladesh is 3–7 mg/litre, which is relatively safe, and in the cleanest rivers of the world, it is generally 2–5 mg/litre.

Water pollution poses serious risks to public health. Drinking and using polluted water increases the risk of diseases such as diarrhoea, cholera, typhoid, hepatitis, and other waterborne and water-based diseases. Heavy metals (such as lead, mercury, and cadmium) and toxic chemicals can enter the human body and cause nervous system damage, kidney failure, and intellectual development problems in children. Poor urban populations—especially those who use polluted water due to a lack of clean alternatives—are the most affected.

Environmentally polluted water is also extremely harmful to aquatic life, as fish and other aquatic organisms die due to a lack of dissolved oxygen. Additionally, the natural ecosystems of rivers and water bodies are being destroyed, negatively impacting the food chain. This is contributing to the decline of fisheries resources and the extinction of many fish species in the peripheral rivers of Dhaka. When polluted water is used in agriculture, crop production decreases, toxic elements enter the food chain, and soil fertility declines—posing long-term health risks for humans.

There are several important laws in Bangladesh to prevent river pollution, enacted for environmental protection and sustainable management. These include the Bangladesh Environment Conservation Act, 1995/2023, the Bangladesh Water Act, 2013, and the National River Protection Commission Act, 2013. These laws contain strict provisions to prevent river water pollution.

According to the Bangladesh Environment Conservation Act, if any person or organisation engages in environmental pollution, there is a provision for various terms of imprisonment, fines, or both. Under the Bangladesh Water Act, 2013, if any person or organisation disrupts or pollutes the natural flow of a river, they can be punished with up to five years' imprisonment or a fine of Tk 1 million, or both. The National River Protection Commission Act, 2013, empowers the commission to take strict action against river encroachment or pollution, and the guilty party can be punished for land encroachment and water pollution.

However, due to the lack of effective enforcement and the absence of proper monitoring systems, river pollution has not yet been controlled—posing a serious threat to the environment and public health.

It is necessary to take protective measures to prevent further degradation of rivers and to conserve water bodies. Water quality indicators are strongly correlated with the expansion of urban areas. As water bodies shrink, water quality deteriorates over time.

Water pollution in the rivers around Dhaka is a complex problem that requires the combined efforts of the administration, industries, civil society, and the general public. We can combat this pollution through legal enforcement, infrastructural development, public awareness, and sustainable development planning. We all need to work together to ensure clean and pollution-free rivers for future generations.

Dr Shafi Mohammad Tareq is a Professor in the Department of Environmental Sciences at Jahangirnagar University.

Comments