For a long time, people have made the derogatory word mofiz synonymous with the residents of the Rangpur region. This indignity signifies an underrating of the people of Rangpur based on poverty and poor living conditions in the northern part of Bangladesh. Today, the mention of mofiz commonly implies a simpleton. This buzzword layers in nation-building history which brackets in the struggles to grapple with the shackles of poverty as endemic in the country. However, the prevalence of the word mofiz belittles someone and assures a stereotyping of the people of the northern region spurring no introspection into the aversion embedded in the term. This neglect then flattens out the historical conditions which have marred the Rangpur region prevalent today but ongoing since the colonial period.

Trivial usage of the loaded term even gravitated to leaders in the now fallen, then ruling party. Asaduzzaman Noor, in a public rally in 2023, lauded the wave of development under the Hasina regime, recalling the difference to shoddy infrastructure under other governments in Nilphamari and other northern areas. Noor called out Ehsanul Huq Milon, a former BNP Minister for labelling people from the north as mofiz. Noor took credit for his party's success in developing infrastructure in the north citing the daily eighteen flights Syedpur airport as a clear example. Rather, he labelled the BNP as the only remaining mofiz in the country.

Identifying BNP as mofiz notes the party as simple in thought and slow in action. Such remarks to scorn the opposition fell in line with similar comments directed at slighting the opposition by the totalitarian party in power. Be it a political party that uses the term mofiz to describe political inaptitude, the quick usage of the term implies the quickness of politicians to use the jab. The term mofiz has entered the urban jingo to stereotype the people of the north. It is not politicians alone who use the term, but everyday users who repeat it and almost institutionalise the erasure of the plight of the people being described, let alone otherising the people of the north into a certain pejorative demeanour.

The Waterscape

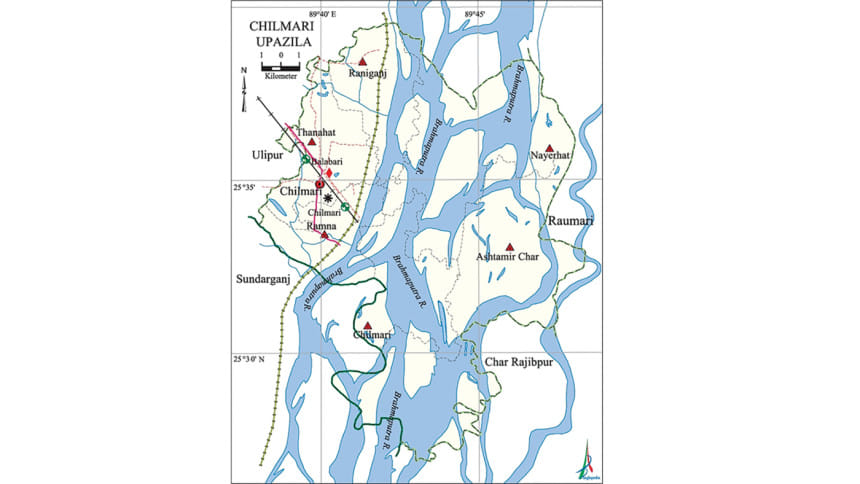

Chilmari is one of the poorest parts of Bangladesh, with over 77% of people living below the poverty line. Sitting on the Brahmaputra floodplains, it's hit hard by seasonal flooding and erosion, forcing Chardwellers to constantly rebuild, often in new chars. This constant displacement disrupts income and keeps people stuck in poverty. In the monsoon, there's no work due to widespread flooding. Most income is earned between late October and early June, and that must stretch through the monsoon. The pre-harvest period brings monga, a seasonal famine. Living hand-to-mouth, savings run out fast, and every year the struggle starts over. The floodplains make it hard to generate stable income.

Political crises, alongside constant flooding and erosion, continue to push Chilmari's Chardwellers deeper into poverty. During the 1974 famine, they were among the hardest hit, with Basanti's image drawing global attention. In response, seasonal migration became a key coping mechanism. Since the 1970s, many men have travelled to Dhaka around October in search of short-term work. Economic growth in the capital created opportunities in sectors like garments, construction, and rickshaw pulling, despite the risks involved. These migrants typically return by early December, as Hemanta (late autumn) ends, and the agrarian season begins along the Brahmaputra's fertile banks.

Two narratives of the term Mofiz circulate in Chilmari and among the char diaspora in Dhaka. One traces back to the late 1970s, when a direct bus service from Chilmari to Dhaka opened up seasonal labour opportunities in the capital. The service, launched by an entrepreneur named Mofiz, grew into a profitable business. As busloads of labourers arrived in Dhaka, they were given chits stamped with Mofiz. As demand for workers grew, employers began saying, "I need a mofiz." The chit signaled that once work was done, the labourer would be returned via the same bus. Over time, Mofiz became a label for char migrants as disposable labour, tied to a bus route, and shaped by the state's neglect of river-induced hardship.

The other story tells of a man named Mofiz from Chilmari who arrived in Dhaka and struggled to navigate the unfamiliar city. Differences in language and behavior marked him and others like him as outsiders. Urban residents began to see Chardwellers as simple, unsophisticated, even backward. Over time, Mofiz became a stereotype, used to label incoming migrants as people unfit for the pace and complexity of city life. A name born from hardship turned into a slur that reduced survival into shame.

Colonial Roots of Otherisation

British colonial records painted the chars of Chilmari as volatile spaces rife with trouble. A 1907 report described these areas as violent frontiers. Because of this, the chars became fixed in the colonial imagination as wild and dangerous lands. This perception did not disappear after colonial times but continues to affect how people view and treat Chilmari and its residents. The British often portrayed the locals as tricky or untrustworthy. For example, a settlement officer in Rangpur noted that when asked for directions, locals often replied, "Mui Chengra Manish Babu, Mui Ki Jannoo," meaning "I am just a boy Sir, what do I know." The respondent was confused because river routes were complex and giving wrong information could cause trouble. Yet colonial officials took this as proof of their unreliability. This kind of labeling entered official records and helped build the stereotype of Mofiz as backward and simple.

The colonial rulers wanted to incorporate these lands and people into their system in a way that allowed better control. They portrayed the Chardwellers as both helpless and violent, which pushed them out of the national picture. Whether in Dhaka or London, the mention of "Char" or "Chilmari" evokes predictable responses. Any time I mention research in Chilmari, I receive the response "Oh, mofiz," which exemplifies the baggage attached to the place. Similarly, when I mention the chars, or the chars of Chilmari specifically, people often ask, "Do lathiyals still operate there?" Mining into the crevices of colonial history, one can trace a connection between the colonial history of land-making and the otherisation of char dwellers, namely from Chilmari.

Lathiyal (stickbearers) or lathiyal bahini (gangs of stickbearers) actively guarded char land. When land disappeared, everyone lost control, but once it re-emerged the landowners needed to regain it. Each large landlord patronised lathiyal bahini (battalion) who fought battles with others of the same occupation to take control over the newly emerged char. Though the prevalence of lathiyals faded in recent years, the legacy still remains as the mere mention of chars conjures images of stick-laden bloody brawls. One such depiction can be found in the Subarna Mustafa film Gohin Baluchor released in 2017.

Colonial documents also raised concerns about squatters and opium trafficking in the region. These squatters were mostly displaced farmers from nearby districts who lost land due to erosion. At the same time, industries in Assam required labour. The empty chars near the Brahmaputra became a stopping point for displaced people either moving on to Assam or trying to settle down. These migrants, known as Bhatias, challenged colonial authority. Zamindars' agents lent money to these settlers hoping to make them labourers and keep control. But many could not repay their debts, leading to conflicts and forcing them to move again. Officials labeled the Bhatias as unreliable and noted they preferred Assam's charlands because those areas had fewer land laws. This portrayal criminalised their mobility and linked char settlements with disorder. What was really happening was not just prejudice but colonial accumulation from unstable lands. The chars and their inhabitants were made to seem disposable and wild to justify continued colonial exploitation.

This long history of colonial othering still shapes how the state talks about the chars and influences public perception. Because of this, chars remain marginalised in the national imagination. The people of Chilmari and similar areas are still belittled or dismissed through terms like Mofiz, which have roots in colonial stereotypes. This legacy, born in colonial times, continues through modern governance, limiting how these communities are understood and treated, which becomes explicit in everyday language in the city.

Erasing Identity at Scale

It's not just the term Mofiz used in the city or the colonial enframing of chars as violent and criminal frontiers and people in the north as simple, Chilmari itself holds within it layers of differences amongst its residents in the chars and in qayem (stable, mainland). In Chilmari, locals distinguish between Bangals, who speak Rungpuriya, the dialect and Bhatias, who speak a mix of Mymensingh and Rajshahi dialects. Despite differences in identity, they intermarry, share daily life, and face the same instability shaped by erosion and state neglect. Over time, the informal line between Bangal and Bhatia has thinned, replaced by a shared sense of what it means to live in the chars.

But the same response does not measure up to the mainland view on chardwellers. Terms like Bhatia or Charua are used with judgment. "Oh the Bhatia, they eat too many spices," someone might say, as if the river gave them a different nature. They're called bold or too wild as shaped by the flow of the river unlike mainlanders, who, at least for now, are spared that chaos. Some even call them "Rohingya," like they don't belong. "Everyone in Chilmari is a Rohingya then," a Chardweller replies insisting that in the Bengal Delta, it is very much possible to lose all kinds of land in a go and therefore, everyone technically lives on chars and could face similar belittling someday, perhaps soon, perhaps intergenerationally later.

Everyday Language as a Barrier to the Way Forward

People living in the chars are not just geographically remote; they are continually made socially distant as well. Mainlanders and urban folk alike taunt them, often without reflection, for the very environment they are forced to adapt to. Both state and society treat the riverine lands as homes to the vulnerable who are also called "backward," reinforcing a narrative of marginalisation.

The casual use of terms like Mofiz normalises exclusion. The name developed among migrants grappling with poverty, land loss, and state neglect. It once served as part of a survival vocabulary, a marker of resilience for those navigating erosion, displacement, and hardship. But over time, rather than representing struggle and endurance, Mofiz has become a shorthand for stereotyping entire communities.

When politicians use the term Mofiz to mock their opponents, the real issue lies in a collective language of humiliation. Geography and history are flattened into a slur, stripping people of their stories, respect, and context. Certainly, the cause for concern extends beyond a single word. Rather, the inability to keep up with differences layered in environmentally fragile areas causes worry. Soaring levels of climate-induced migration from low-lying regions like Chilmari have been predicted. If Bangladesh continues to turn ecological vulnerability into cultural inferiority, then future displacement will be met not with solidarity, but with more othering.

The plight of the displaced in adjusting to the new climates warrants critical attention. Readiness to address environmental issues requires awareness of the language used to describe populations. Perhaps practices of stereotyping threaten populations in need of a better environment more than the climate itself. Talking about Mofiz should not be confined to a side issue, but rather tells a worrying sign of institutional shortcomings where the usage of such terms is not discouraged.

The word Mofiz thus points to the bigger story of how Bangladesh still struggles to make space for its own diversity.

Dr Saad Quasem is a Lecturer in Anthropology and Climate Change at SOAS, University of London.

Comments