Empowering youth in an uncertain world

We are living in both exciting and dispiriting times. On one hand, we are witnessing extraordinary advancements in technology that are connecting us in ways that were once unimaginable. On the other, we are seeing an uprising of populism and a rejection of globalisation. While Uber launches in Dhaka, their engineers in Silicon Valley are experimenting with driverless cars. We are also seeing, simultaneously, societies turning inwards, looking to close borders and build walls, manifested recently with Brexit and the outcome of the US presidential election. There seems to be a crisis in leadership. Where have all the good leaders gone?

Another dimension to the current global complexity and chaos is the deepening rifts in ideological beliefs, widening income gaps between the rich and the poor, and the new reality of global terrorism. In such a world, I cannot help but feel compassion for young people, globally, and especially in Bangladesh, where more than 52 percent of our population is below the age 25. Growing up today is not easy. Too many distractions and too many competing values. What should young people believe in? Who should be their role models? How are they to prepare themselves to survive and thrive in this fast-changing world? In a shrinking space for dissent and dialogue, can the youth be hopeful about bringing about change?

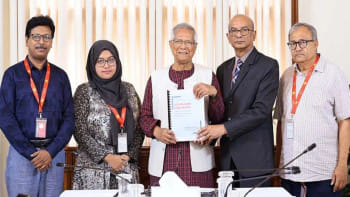

It was with the conviction that young people can, and must, be empowered to be agents of change—not just passive observers of events, but shapers of history—that we developed the idea of Bangladesh Youth Leadership Centre (BYLC). Our idea was simple: unite youth from diverse backgrounds, instil in them values of inclusiveness and tolerance, ignite in them a sense of purpose, and equip them with leadership skills. And eight years on, today, more than ever before, I feel that the solution to many of society's urgent needs is in building the leadership capabilities of young people.

However, what does building leadership capability mean anyway? Is leadership something that can be learned? My experience of working with over 3,000 of the brightest school, college, and university students of Bangladesh has taught me that when young people from diverse backgrounds come together and work towards a common cause, they can accomplish extraordinary things. I have seen our students challenging stereotypes, breaking barriers, collaborating across regions and religions, and creating successful enterprises. I believe, therefore, leadership can be learned.

To become a good leader in the 21st century, in my opinion, one must develop five capabilities. First and foremost is self-awareness—an understanding of one's strengths, weaknesses, values, and purpose. Second is contextual awareness—an understanding of the external environment and the context in which one operates. Third is a strong moral compass and the ability to differentiate between right and wrong. Fourth is the capacity to communicate effectively, work across boundaries, and mobilise others for action. And finally, given the rapidly changing nature of the world we live in, a good leader must be adaptive—able to reflect and act at the same time, have an experimental mindset, be open to failure and be quick to make mid-course corrections.

I have also realised that the crisis we see in leadership today, both in Bangladesh and globally, is to a large extent due to our flawed understanding of what leadership actually means and what qualities we should seek out in the people we are choosing as our leaders. We often equate leadership with prominence and dominance: the person at the front, loud, and commanding our attention gets called the leader. There is merit, however, in differentiating between leadership and position or title. In his seminal book Leadership without Easy Answers, Harvard professor Ronald Heifetz argues that the idea that leadership is an innate characteristic, something one is born with, is problematic for two reasons. First, it can lead to hubris, and often harmful behaviour on the part of the person who thinks he or she is a born leader. Second, people who think they are not born leaders avoid taking responsibility, thus depriving society of their collective intelligence and contribution.

Indeed, it is much more useful to perceive leadership as an activity, which can be exercised by anyone, regardless of age, gender, or position to improve the human condition. This idea of leadership is particularly relevant for Bangladesh where we have a bulging youth population. Imagine how our country would look like if every single young person took ownership of our problems, took initiatives, and exercised leadership to make a positive difference.

With high youth employment, disenfranchisement, and polarisation in the country, there is a strong need to invest in leadership education for our youth. A recent paper by the a2i programme of the Prime Minister's Office stated that there are currently 19.3 million youths in Bangladesh who are not engaged in any employment, education or training. The underemployment rate is 18.7 percent and a staggering 19.45 million are in want of decent work. Whether this large number of youth will become our asset or liability will depend on how well we equip them with skills that are relevant for the 21st century workplace.

The challenges of skills gap and unemployment are further exacerbated by the new phenomena of youth radicalisation. While there are several probable causes of this, I would like to put forward two root causes. First, the education system in Bangladesh does little to foster creativity and critical thinking in our students. From primary school to university, we teach our students to memorise and learn concepts without knowing how to apply them in real life. Our focus is more on grades than on knowledge. Therefore, we are producing graduates who do not have the problem solving or communication skills to excel in the workplace. And second, we have a divided education system—English medium, Bengali medium, and Madrasa—and students from these different backgrounds lead parallel lives and rarely interact with each other. This causes tension, mistrust and a lack of appreciation of the 'other'.

At BYLC, we try to address some of these challenges by bringing together youth from each of the three different educational systems and creating a platform for them to find common grounds and work together in teams. This appreciation of the 'other' is central to our approach of building an inclusive society. When I first noticed apprehensive interactions between a girl from an English medium school and a boy from a Madrasa in the BYLC classroom grow into a friendship, I was struck by how remarkable it was that all it took to break barriers and build bridges was to put these seemingly different individuals in the same room, teach them the rights skills, and give them a problem to solve. Differences fell away as the focus was on the work at hand. Of course, it hasn't always been smooth sailing; feelings have been hurt and uncomfortable truths surfaced, but this is how empathy is learned. It is messy, slow, and painful at times, but imperative nonetheless if we are to have young leaders who can cross boundaries and engage with others of different values.

There is a dire need for good leaders today. We need good leaders and role models in public, private, and civil sectors. But good leaders are not created overnight. They need to be trained. Our level of commitment to invest in developing the next generation of leaders will determine how well we can reap the benefits of our demographic dividend. The perils of youth disenfranchisement are real. Events in recent months have taught us how critical it is for us to channel youth energy in a positive and constructive direction.

As schools, college, and universities across Bangladesh explore strategies and options to prepare students to meet the complex challenges of the 21st century, I would make the case for incorporating youth leadership programmes as a core part of curriculum. An experiential, action-based learning model can be effective in giving the younger generation a sense of purpose, the desire to constantly learn and grow, and the empathy to serve others. By equipping our youth with leadership skills, we can enable them to lead change in the different roles they take on in life. Whether they work in multinational companies or NGOs, run startups or run for office, as long as our youths are capable and adaptive, and as long as they take ownership of our collective social challenges, we can be optimistic about our future. The youth of Bangladesh can take us one step forward to making our vision of an inclusive, just, and prosperous society a reality.

The writer is the president of Bangladesh Youth Leadership Centre (BYLC). Comments can be sent to [email protected]

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments