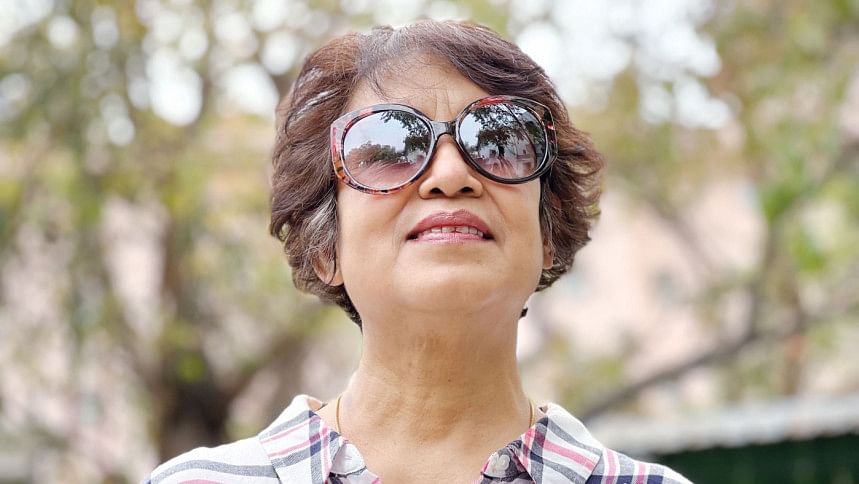

I have every right to return to my country: Taslima Nasrin

Ever so outspoken, ever so controversial – Taslima Nasrin has continued to advocate for free speech over the years, after she was forced to leave Bangladesh in 1994.

Owing to her thoughts and ideas, the now exiled author is banned from both Bangladesh and West Bengal. However, the indomitable spirit continues her brand of activism through pen and paper, and social media.

Hashibur Reza Kallol, Editor of The Daily Star Multimedia, talks to Taslima Nasrin about her past, her thoughts on the state of Bangladesh, and her desire to return, in an exclusive interview.

"I can't help but protest -- It feels wrong not to," she says. "28 years ago, I was forced to leave my country. Still, no government in Bangladesh has let me return." Nasrin asserts that the many wrongdoings, coupled with the lack of free speech and democracy in Bangladesh, has made her a defiant author. "Maybe I will not be able to live in Bangladesh, maybe I will be killed once I go there. However, I have every right to return to my country."

Nasrin comments that even if one person feels 'enlightened' by her work, she will consider herself successful in her mission to propagate free speech.

The author continues to courageously speak up against wars, Hindu-Muslim clashes and attacks on women, among other issues on social media.

Taslima Nasrin started publishing prose in the early 1990s, and produced several essays and novels before the publication of her 1993 novel "Lajja", which is a response of Nasrin to anti-Hindu riots that erupted in parts of Bangladesh, soon after the demolition of Babri Masjid in India in 1992. The book indicates that communal feelings were on the rise, the Hindu minority of Bangladesh was oppressed, and secularism was under shadow. It changed Nasrin's life and career dramatically, as she wrote against Islamic philosophy, angering many Muslims. It sold 50,000 copies in Bangladesh before being banned by the government.

Nasrin has written 45 books so far, several of which are banned by the government of Bangladesh. According to her, prominent Bangladeshi publishers do not publish her books now, as they are afraid of being 'hacked to death' by fundamentalists. Many of her books are being published and sold illegally. When she lived in Bangladesh, she wrote for various newspapers. "All of them have stopped publishing my writings now. The Indian media, too, is afraid of supporting me, but I am not surprised by it at all."

"When I started writing in the 70s, I wanted to write beautiful novels about love and nature and the complexities of human relationships," says the author, reminiscing her start in the industry. "However, I could not turn my back on whatever was happening in my country— I feel like it is my job to speak up against injustice and oppression," she explains. "I still enjoy poetry. In the 70s, I wrote a lot of poems. Around 12 to 14 of my poetry books were published. After that, when I became occupied with writing columns and essays, I took a break from writing poems. But I have started again now."

Besides "Lajja", some of her notable works include "Dwikhandito", "French Lover" and "Amar Meyebela", among others.

She believes that although many resonate with her philosophy, most are apprehensive about befriending her or talking about her works -- they are afraid of becoming targets.

"I have heard of people being attacked by fundamentalists, for simply liking my writings. Regardless, many have been quite outspoken, supporting me publicly. They are such courageous souls," she adds. "However, I miss the way that people used to adore me when I was in Bangladesh, it was special. They used to gather around me for my autographs at various book fairs."

Nasrin misses going to the Ekushey Boi Mela. "I meet readers of my Hindi and English books at the World Book Fair or Delhi Book Fair, but they are not readers of my Bangla books. I miss my people, but what can I do?", she laments.

"I am a strong advocate of women's rights, freedom of thought, and human rights. What better causes are there to write about? Still, I am continually being boycotted and censored. Anyone else in my situation might have abandoned writing, but I haven't."

Apart from being a writer, Nasrin is also a physician, having studied medicine in her early years in Bangladesh. She used to live in Armanitola. During her long exile, many of Nasrin's loved ones passed away. She wrote about them in the seven volumes of her autobiography— she compares it to the seven volumes of "Ramayana", calling it her "Taslimayana".

As Nasrin does not live in Bangladesh now, she is not really familiar with the work of contemporary Bangladeshi authors. "I read what I can through Facebook, especially the writings of people who speak up against injustice. There is so much corruption, misogyny, and bigotry going on in Bangladesh. I read the views of people who regularly protest against such things online," she asserts.

The author is glad to see that many women have picked up the pen to voice out against injustice. "It was not like this before, I was quite alone. As a result, I became the target of unfair treatments and torments. Nobody spoke up the way I did," she explains. "Now, there are not only women, but also men who take cues from my work. I see many appreciating my philosophy on Facebook and spreading the word. It brings me happiness."

Nasrin was banned from Facebook for one week because of one of her posts, but she asserts that at times, such bans can last for months.

"Facebook is the place to speak for people like me, whose books or other works of art have been banned or censored. We could express our opinions freely on the platform. But now, Facebook bans people like us because of reports from bigots, misogynists, and conservatives. This is unfortunate. Where is our place then?" she questions.

"People who believe in freedom of speech and criticise religious fundamentalism and patriarchy have to write cautiously now, so that they don't get banned from social media platforms like Facebook and Twitter. This should not happen. Everyone, not just writers, should have the freedom of speech."

That being said, she understands that not every writer is in need of freedom.

"There are a lot of people who write love stories, poems, and pieces on nature. They are never in trouble. They are never banned. There is no price upon their head. They don't get attacked or hacked. They are not forced to leave their country. So, they are not in need of freedom of speech. Opinions that are not favourable to a patriarchal, conservative society agitate bigots, fundamentalists, male chauvinists, and misogynists. As a result, governments become concerned and send the opinion holders to jail or exile, or religious fanatics hack them to death — these are the people who need freedom of speech. We expect governments to ensure the freedom and security of such people," she says. "I have not been allowed in my country for 28 years. What does that tell you? It tells you that this government does not believe in freedom of speech. All governments are against free speech, just like fundamentalists. They try to silence us."

Taslima Nasrin believes that bigotry and fundamentalism have engulfed Bangladesh. She adds, "Today, many young girls wear burqas and hijabs. It was not like that back when I was in school. Child rapes, child murders, and drug dealings are happening at madrasahs, but they are given so much leniency. While they are pulling the society backwards, those of us who dare protest are either in jail, in exile, or hacked to death. What is the government doing? Nothing!"

When the author first came to India, she dealt with many obstacles. She was denied access to Aurangabad because Muslim fundamentalists rallied against her going there. Her book, "Dwikhandito" was banned in West Bengal for two years, alleging insult of religious beliefs and obscenity. The production of her mega serial, "Dusshohobash '' was stopped, and the inauguration of her book, "Nirbashon '' was cancelled in the state. Nasrin continues to live defiantly, refusing to keep silent in the face of bigotry: "Where there is any injustice, I protest in my own way through my writing. I am a writer. I don't take to the streets."

Keep your eyes on The Daily Star's YouTube channel for the exclusive video interview.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments