Conquering the wild seas

Think wildlife conservation and what first comes to mind are men in grey or beige toned outfits and names like David Attenborough, George Schaller, John Muir, and Roger Payne. Women conservationists are few and numbered. But they are true trailblazers as they leave their mark on this male-dominated profession. Jane Goodall, Diane Fossey, Sylvia A Earle and Rachel Carson have all influenced a generation of young women with their work with chimpanzees and gorillas facing extinction, and their hard-hitting prose catalysing the modern environmental movement.

In Bangladesh too, the field of wildlife conservation is seeing an overhaul and hopefully an eventual narrowing down of the gender gap, thanks to the ladies conquering the seas and the land of the deltaic plains of Bengal. With international days celebrating the diversity of life both at sea and on land in the next few days, it felt appropriate to talk about conservation and ladies of the sea.

The Sea Warriors of Bengal

My research led me to some brilliant women dedicating their lives to wildlife conservation. Below are snippets of the conservationists'—Alifa Bintha Haque, Manzura Khan and Shamsunnahar Shanta—take on the lives of female conservationists in Bangladesh.

For Manzura Khan, manager of the Marine Protected Area Program at Wildlife Conservation Society (WCS) Bangladesh, childhood was spent in Khulna in southern Bangladesh, home to the largest mangrove forest in the world.

Manzura struck me with her wide smile, her wiry straight jet-black hair and her knack to hold a conversation anytime, anywhere.

Despite, growing up in a fairly conservative setting in rural Bangladesh, the support of her family allowed Manzura to nurture her dream of working with nature. She was always geared for a life in the wild. Her degrees in Fisheries and Marine Resource Technology from Khulna University and Master's degrees from Bangladesh Agricultural University (Mymensingh) in Aquaculture and then from the University of Tromso in Norway and NhaTrang University in Vietnam in Fisheries Aquaculture Management and Economics, are testament to that.

Manzura has made a career in working with aquatic animals and over the years, she has accumulated a host of conservation stories to share.

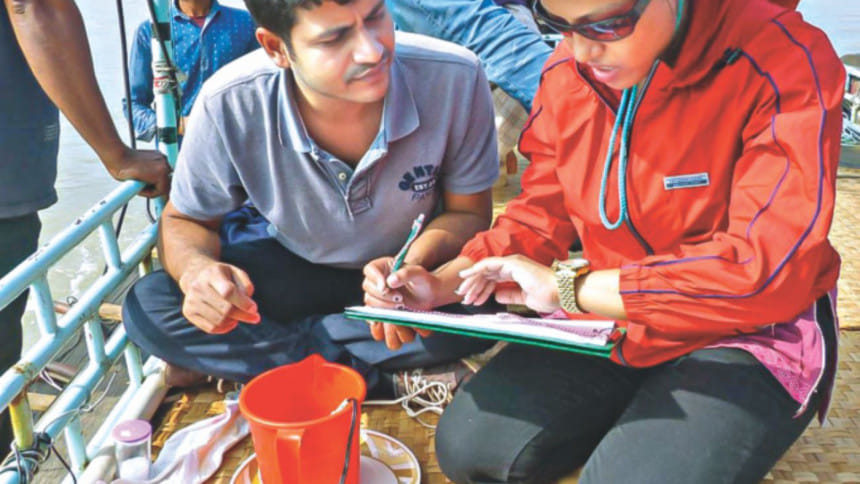

Her absolute favourite is the one where she had to spend more than a month on an artisanal fishing boat smack in middle of the Bay of Bengal surveying for dolphins, porpoises, whales and marine turtles, and conducting investigations on sharks and rays caught in fishing operations. This was between December 21, 2017 and January 31, 2018, when WCS conducted a survey along the coast of Bangladesh to determine conservation implication. The team covered up to 50 kilometers offshore along the Bangladesh coastline on hired fishing trawlers modified to accommodate the team.

"It is hard to describe what I felt when I first laid eyes on the boat where I would spend a whole month. It was a mingling of my gripping fear of sea sickness and the excitement of seeing marine cetaceans and marine megafauna in the wild. Our survey vessels—essentially wooden fishing trawlers—would be home to the entire survey team for a month. We had an improvised kitchen in the hull and the most basic toilet facilities. There were two boats out on the sea and we had VHF antennaes for communication. There is no mobile network out there."

"I got sea-sick on day one and could not even hold the binoculars for sighting dolphins or porpoise or record any environmental parameters or fishing vessels. The constant rolling of the boat on the waves pretty much rendered me useless."

"It was the excitement of sighting a marine dolphin in the open water that finally lifted my spirits. And as the days went by, I slowly got accustomed to it," says Manzura.

It may sound like fun, but Manzura's work is not easy by any means. In their time surveying out on the sea, the team came across many horrific sights of rays and sharks being pulled up by fishermen at sea or carried to shore at port stops.

"The sheer number of sharks and rays that land daily across the coastal areas is mindboggling. We have also documented wide-spread consumption of ray meat throughout coastal communities. The international demand for shark fins, ray skins and gill plates are likely fueling the trade, much of which is destined for export," she laments.

Manzura also hopes that the research findings will be turned into effective national policies and regulations embraced by all relevant stakeholders.

In contrast to Manzura's childhood, conservationist Alifa Bintha Haque grew up in Dhaka, went to school and college here and it was not until her application for masters' that she became sure of her passion.

"Water," she says sheepishly. "I know it sounds strange, but that is my passion."

Alifa grew up with an already established societal standard of how a woman should be and behave. "So, I grew up somewhat clueless, somewhat bound by standards already in place with what I should make of my life. The only expectation I had to meet was that of my parents."

"I completed my undergrad from the Department of Zoology at the University of Dhaka and also did an MS in Fisheries. But come time to choose a career, I was not happy with the options. I ended up planning another Masters in UK."

"While writing my statement of purpose I realised I had to be honest. I wrote of my passion: Water. It sounds bizarre maybe but water bodies give me a certain sense of home, belonging. I wrote that I wanted to work with aquatic systems and that's as far as I knew."

"I came back in 2014 after my masters. Inspired by a professor in UK, I took every chance I got to visit our coastal regions. I remember visiting Cox's Bazar, Teknaf and St. Martin's Island more than 25 times that year. It made me realise how much was left to do in the marine conservation sector and how little we knew," opines Alifa.

After a teaching stint at North South University, Alifa joined the Department of Zoology at the University of Dhaka in 2015.

"I started working on my projects emphasising the conservation of sharks and rays in Bangladesh. In 2017, I collaborated with WCS. I worked in the trade dynamics of elasmobranchs and its international paradigm as well."

Alifa has a few projects under her belt. From working for conservation of Sawfish in Bangladesh to identifying the Trade Chain of Shark Products, she spends days working in close proximity with the fishermen in Bay of Bengal.

"I used to constantly talk with fishermen. Sit with them for meals and evening tea. It is considered a bad omen if a woman gets into a fishing boat and I was amazed when one of the fishermen asked me to hop into one of his boats on the sea saying it is alright for me to be on their boat. I realised then, that my work was finally showing fruit and I was gaining their trust."

"I am amazed by the diversity at sea. I work with Sawfish now. I have come across Sawfish that need an entire truck to be hauled! These are the giants that lurk in our seas."

"I always carry two books with me on the field – Thoreau's Essays and The silent world by Jacques-Yves Cousteau. They have changed my life and my philosophies," she says.

She spends long days and nights on the field, often starting work early in the morning when all of the catch from the sea lands on the shore so that she can start her data collection which will help her plan possible conservation efforts. She dreams of a country where conservation isn't a work of some activists and scientists but a lifestyle of the people.

I talked to one other conservationist, Shamsunnahar Shanta, the Marine Protected Area Program Coordinator of WCS, Bangladesh.

Like Alifa, Shanta too grew up in Dhaka. "I studied Zoology at Jagannath University. It was here that I learned about biodiversity of Bangladesh and also realised what is at stake. Ever since, I have wanted to work in wildlife conservation."

Following graduation, Shanta started work as an interpreter with floating dolphin exhibitions—Shushuk Mela—initiated by WCS. She later joined WCS Bangladesh team.

Her aspirations to be close to nature also took shape through the field visits she had to make as coordinator of the MPA program.

Shanta was part of the coastal survey conducted by WCS as well. "The time at sea was one of the best times of my life and one of the most intense. The first two days at sea were extremely rough. Sea sickness, the scorching sun, trying to spot dolphins, whales and turtles in the open waters, were both exciting and exhausting."

"I will never forget seeing the first marine dolphins. Watching the pod of dolphins swimming freely out in the wild made all the sea sickness worthwhile," says a smiling Shanta.

During the 40 days spent at sea, the team sighted the largest group of humpback dolphins that WCS has recorded to date in these waters, a huge group of between seven hundred and one thousand Indo-pacific bottlenose dolphins and a mother-calf pair of Bryde's whales near Cox's Bazar.

They also recorded a large number of finless porpoise and Irrawaddy dolphins, particularly around Nijhum Dwip.

For these conservationists, every day is a dual fight, one against social stigmas, where men especially in rural areas are reluctant to let them into their lives, and the other navigating the tragedies of an ocean they have come to love, one under constant threat. From overfishing, climate change, industrial pollution and coastal infrastructure development.

But they are hopeful, that their work will show results and the ocean giants they work so hard to conserve will have a healthy and safe home.

Finally, what better way to end this piece than a line by Sylvia A Earle, seminal marine biologist, "Even if you never have the chance to see or touch the ocean, the ocean touches you with every breath you take, every drop of water you drink, every bite you consume. Everyone, everywhere is inextricably connected to and utterly dependent upon the existence of the sea."

Comments