Sea ice in Arctic shrinks to second lowest level on record

Arctic sea ice this summer shrank to its second lowest level since scientists started to monitor it by satellite, with scientists saying it is another ominous signal of global warming.

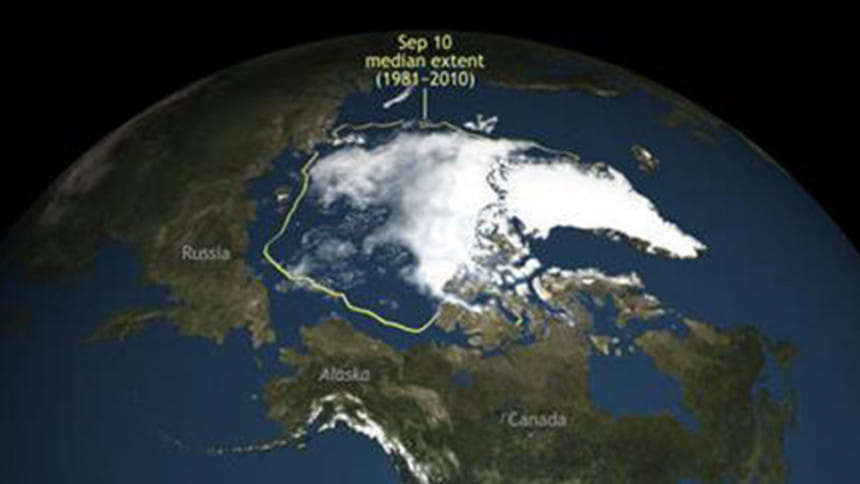

The National Snow and Ice Data Center in Colorado said the sea ice reached its summer low point on Saturday, extending 1.6 million square miles (4.14 million square kilometers). That's behind only the mark set in 2012, 1.31 million square miles (3.39 million square kilometers).

Center director Mark Serreze said this year's level technically was 3,800 square miles (10,000 square kilometers) less than 2007, but that's so close the two years are essentially tied.

Even though this year didn't set a record, "we have reinforced the overall downward trend. There is no evidence of recovery here," Serreze said. "We've always known that the Arctic is going to be the early warning system for climate change. What we've seen this year is reinforcing that."

This year's minimum level is nearly 1 million square miles (2.56 million square kilometers) smaller than the 1979 to 2000 average. That's the size of Alaska and Texas combined.

"It's a tremendous loss that we're looking at here," Serreze said.

It was an unusual year for sea ice in the Arctic, Serreze said. In the winter, levels were among their lowest ever for the cold season, but then there were more storms than usual over the Arctic during the summer. Those storms normally keep the Arctic cloudy and cooler, but that didn't keep the sea ice from melting this year, he said.

"Summer weather patterns don't matter as much as they used to, so we're kind of entering a new regime," Serreze said.

Serreze said he wouldn't be surprised if the Arctic was essentially ice free in the summer by 2030, something that will affect international security.

"The trend is clear and ominous," National Center for Atmospheric Research senior scientist Kevin Trenberth said in an email. "This is indeed why the polar bear is a poster child for human-induced climate change, but the effects are not just in the Arctic."

One recent theory divides climate scientists: Melting sea ice in the Arctic may change the jet stream and weather further south, especially in winter.

"What happens in the Arctic doesn't stay in the Arctic," Pennsylvania State University climate scientist Michael Mann said. "It looks increasingly likely that the dramatic decrease in Arctic sea ice is impacting weather in mid-latitudes and may be at least partly responsible for the more dramatic, persistent and damaging weather anomalies we've seen so many of in recent years."

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments