Tenth, toughest

As we understand, budgets are drawn up to prioritise where to spend money and how to do it. It is also about how to collect that money. The end result would be growth, prosperity and a people better equipped to face the tomorrow.

It seems the results are getting all tangled up now as years of poor implementation (and sometimes faulty planning) is finally taking its toll. We are getting growth but not prosperity, we are getting roads not pliable, we are getting “literate” people but not with quality, we are taking up projects but spending far more than what they should have cost.

The economy is facing strains because of not addressing some basic reform issues and a kind of recklessness compounded by complacency or rather a fatalistic thinking that nothing wrong can come our way. But growth needs reforms and we all the more need it when as our status has moved up to lower middle income country.

The challenges of being a lower middle income country will loom large in the next year and thereafter. Without structural transformation, innovation, improved productivity and governance, the attainment may wane.

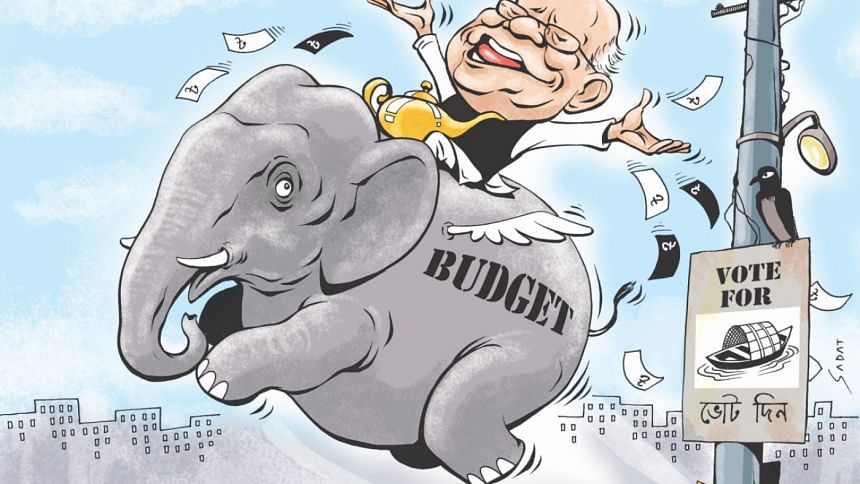

This is the harsh reality that Finance Minister AMA Muhith faces today as he would place his record 10th budget today.

It would be something of interest to know how he would plan and rationalise his above 7.8 percent growth set for the next fiscal year to match with the target of the seventh five-year plan set at 7.3 percent.

Growth itself is drawing questions now.

Bangladesh has been getting faster growth rates in the last one decade touching the 7 percent figure, but it has not been without debates as the recent World Bank, IMF and ADB forecasts show a much lower figure than the government's claim of 7.65 percent for this year. But the figure debate has been overwhelmed by the question of quality. Is our growth really meaningful? Are we getting our potential growth? The answer is a simple NO.

A few examples can elaborate the point. We have got the Dhaka-Chittagong road upgraded to four-lane at a huge cost of Tk 3,600 crore. The net result? It now takes 24 hours to reach the destination. Then why have we spent the money? To get a road that is not functional does not serve any purpose.

We have got the Dhaka-Mymensingh road upgraded to four-lane, but it now takes anything between five and eight hours to reach the destination that should not take more than two hours. Its original cost of Tk 880 crore had crossed over Tk 1,900 crore, an over 200 percent rise. Yet a small rough patch in Gazipur beats the purpose of the road.

So it is not only an issue of projects that are not giving the desired results, it is also a question of at what cost we are getting them. The Dhaka Chittagong highway saw a cost increase by a staggering 77 percent. The Local Government Engineering Department has asked for Tk 750 crore to repair roads that were not properly made.

The Dhaka-Mawa highway that would link with the Padma bridge is set to get costlier by 70 percent and more escalations are on way even before it is halfway done. The list seems endless.

That's only the one side of the story. On the flip side, all these projects got delayed by several years, weakening their economic rate of return and viability. As long as a project is not completed, it is just money spent with no return. And when too many projects get clogged that takes toll on the economy with expenditures without income.

It all then bogs down to a simple transfer of money from taxpayers' pockets to others.

So we are getting a growth that could be gotten at a much lesser price. The money saved could be spent on other productive work, eking out more growth out of the same money. Just as getting more oomph out of an engine makes the car more efficient and desirable, so is the case for a country's economy. Instead, the money is now going to “rent-seekers”, the politically correct term for the corrupt.

The story of our growth is the story of doing and undoing of projects too. Take Dhaka city as an example. Very recently, the footpaths got a glitzy facelift with expensive tiles.

A yellow patch runs in the middle (they said it is for the visually impaired people, but this yellow patch is too difficult for the normal people to walk on). Within months of having it in place, the tiles are blasted away to make way for the metro rail. The perennial road digging is another story of how wasteful we can be. This is what we can call a wasteful growth.

Now let's dwell on the bigger question of whether the growth, whatever its quality, is getting shared with justice. Figures say it is not. Bangladesh was a country of equality for a long time. Now as we look at the income Gini coefficient, the measure for equality in the society, we see a different picture -- it increased from 0.458 in 2010 to 0.483 in 2016.

The question of inequality gets even starker by the fact that there has been erosion in income. At the same time there has been a rapid worsening in the disparity of consumption, income and wealth during 2010 to 2015. The top 5 percent of the society has income 121 times higher than the lowest 5 percent and their wealth is 2,100 times higher. When inequality rises, growth is bound to stagnate.

If we look at the business landscape it is no wonder that inequality would rise. Businesses are growingly turning oligarchic with a few groups holding the sway over contracts and access to facilities. This happens, in Nobel winner Douglas C North's theory, when a society embraces limited access orders where the political elites divide up control of the economy, sharing rents among themselves.

The other story is growth not creating jobs. The spectre of a jobless growth that all had been talking about years ago seem to have come true. The worrying thing is getting higher education is not gaining jobs for the youths, making it essential to rethink development. With this the whole range of issues such as education system, quality and appropriateness come to the surface. The recent figure given out by the MCCI chief Nehad Kabir that every year $6.8 billion goes out in remittance from Bangladesh only shows how we failed to build our skills even in the most significant garment industry.

The economy itself is increasingly becoming less and less knowledge intensive as the Harvard University's Centre for International Development's Economic Complexity Index that measures an economy's knowledge intensity has shown. Bangladesh remains always in the negative on the index, meaning our economy is operating at the very basic level of technology and skills.

Other than this growth story, a few more things are happening in the economy that strain the economy further. Private investment has stagnated and with that credit growth in the private sector too. Or it may be a story told the other way round.

Unabated mismanagement and corruption of the banks have left them dry, leading to a severe credit crunch. Investors are not getting funds from the banks, or even if they get it they have to pay a very high interest rate, leading to a rise in the cost of business.

This has widespread implications. Loss of competitiveness will make our exports lose out to others. Inflation will grow -- it is already heading north -- leading to demand slump. This at a time of income erosion will have strapping impact on consumption.

This will lead to lower production, lower jobs and lower growth from the private sector.

So a banking crisis will ultimately lead to an economic setback as has been the case for India where piling bad loans has sparked fear over its economic outlook.

The other stress is arising from the record current account deficit of $7 billion from last year's $1.3 billion on account of surging imports mainly because of the spree in infrastructure projects. Taka has already weakened against dollar because of the situation, leading to fears of imported inflation.

The pressure on our reserve has grown and will further intensify when loan repayment for mega projects will begin in a few years' time. With imports outpacing exports growing at 7 percent and remittance a better 17.7 percent, the challenge on balance of payment will be a daunting task to withstand.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments