Beneath The Shine

Bangladesh is caught in a limbo between dreamy possibilities and the nitty-gritty of reality. The possibility of moving at a much faster rate is tempered by the grim reality of the current architecture that denies that speed.

We have to be satisfied with a moderate budget -- something that never crossed 13 percent of GDP – because our implementation capacity is hobbled. We have to live with the perennial tailbacks that slow down economic growth. We are stuck with an ugly urbanisation that denies any aspirations of sustainable living in the present and in the future.

Generations are growing up with an education the quality of which falls far behind global standards. The rickety health care system breeds more frustrations than cure.

Yet Bangladesh has achieved a broad-based growth that has trickled down. We have crossed 7 percent growth rate and clocked per capita income of $1,600. Its extreme poverty has lessened significantly. Inequality declined. Life expectancy climbed up.

WHAT LURKS IN THE SHADOW

But it is only part of the story. Even the social indicators need another look as figures will tell a different story also if one reads between the figures. For example, more than 20 million people still live in extreme poverty, or consider the fact that one fifth of the primary school going children have not ever been to a school. Or that our child mortality is still way too high and maternal death rate falls short of MDG goal. And half the population still does not have a system of sanitation in place.

Nevertheless, a new mindset has been created – a belief that we can fix a situation if we want to. The remedy to the power problem is a case in point.

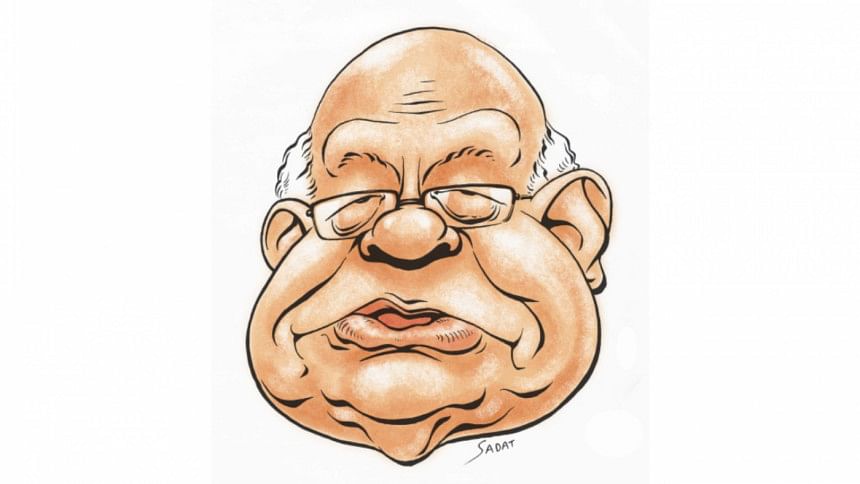

So when Finance Minister AMA Muhith will present the new budget today, he will have to find a solution that will put Bangladesh on a high speed lane that we have been talking about for so long. And he has to sustain and strengthen many of the achievements we have made.

Not only that, he will face some new, emerging challenges this year that may threaten to upset the cart.

The drying up of remittance and the dip in exports are the new headaches this year and a lot of the economy's health will depend on how Mr Muhith devises a way to extricate the country of this sticky situation.

The relentless flow of funds from the workers in the Middle East that had kept our foreign exchange reserves ever buoyant is petering out fast. Remittance growth is already heading south as the petro-economies are smarting from the sustained low oil price. Exports have hit a rough patch because of Brexit, a sluggish global economy and internal structural factors. In many years our export growth has ended the double digit growth and almost touched nada. We are yet to feel the pressure on balance of payment but we might experience it with any upswing in imports and external shocks anytime.

STARK REALITIES IN STATISTICS

We are enjoying the benefits of a stable macroeconomic environment. The GDP is growing but fewer jobs are being created. The latest BBS figures expose this stark reality of jobless growth. BBS has compared two sets of data – from 2010 to 2013, a period of three years, and from 2013 December to 2015, a period of one and a half years. During 2010-2013, when GDP growth was in the territory of 6 percent, 40 lakh new jobs were created. But during 2013 to 2015 when growth was much higher, only 14 lakhs jobs were created. We also see a stagnation of private investment that explains, at least partially, why enough jobs were not created.

When jobs are slow to come, the government's imposition of VAT on a raft of products to generate money will certainly have a big dent on people's quality of life. A 15 percent is not just 15 percent. It is applied on value addition and so it increases at compound rate as a product passes various phases and hands. So the effective hike in price will be significant.

If growth is for people's welfare and giving them a life of comfort, then the VAT increase will not help in that direction.

BIG SCANDALS, LITTLE ACTION

The economy is growing but one of the crucial pillars of a stable economy -- the financial sector – is bleeding. We have seen big scandals in banks with little actions. In last one year, the amount of default loan has gone up by about Tk 11,000 core that could have completed the main component of the Padma Bridge. This does not reflect the amount that the banks have written off. Realisation of bad debts is very poor, only about 5.5 percent. Top bankers at a recent meeting with the Bangladesh Bank have raised concerns of capital flight and money laundering.

To add to the challenges ahead is the fact that we are going to graduate from the LDC status next year to lower middle income country category which means we will no longer be entitled to certain benefits such as concessional loans, ODA and GSP. The next 10 years will be the crucial preparatory stage for such a transition. We would need special attention and investment in some areas like market and product diversification, productivity enhancement and investment in social issues like improving labour safety, wage increase, and environmental standards. Very little is being done in these areas. What we find in the name of protecting the environment is just shifting the problem from one area to another as has happened in the case of the leather industry relocation.

We need to increase the social sector outlay and unfortunately because of heavy investment in the much needed infrastructure, enough money cannot be found to do this. This poses the perfect 'damned if you do, damned if you don't' situation.

BIG PROJECTS, POOR PLANS

But much of it could have been avoided if the big projects were properly planned and implemented. Any big project has two goals to fulfill -- that it has to end on time and within the budgeted cost and that it has to deliver on whatever it has been built for.

The stark truth of the big projects in Bangladesh is they unfailingly fail to meet the first objective and then more often than not the second one too. Take the example of the recently inaugurated four-lane Chittagong highway project that has overrun its original cost, from Tk 1,655 crores to Tk 3,800 crores, and is yet to be complete. Meantime, the unfinished road is leading to extreme tailbacks at bottlenecks such as the Meghna Bridge and other points that eat up the presumptive benefit of the project.

BIG MONEY, HIGH COSTS

Bangladesh is increasingly resorting to non-conventional sources of foreign assistance. We are taking loans from China, India and Russia. Such sources are easy to tap but lopsided. They lack transparency and clear frameworks. Their cost of fund is high which makes it all the more urgent for us to see that projects conceived of funds from such sources are tightly implemented because any delay means bleeding the coffer. Unfortunately we have yet to achieve that efficiency.

So such delays are causing the same cost being carried over to the year after at the expense of smaller social sector spending and implementation of other much needed infrastructure project -- after all, we do not have an unlimited number of employees to look after a plethora of big projects.

The Indian line of credit is a case in point -- we have not been able to utilise it fast enough. Only 65 percent of the first line of credit has been used --and it had many important components such as rail link constructions along Khulna-Mongla and Joydevpur-Kamalapur corridors which are being delayed for various reasons including land acquisition -- and disbursement of the second LOC has not started yet while a third LOC is being readied for signing.

LESS OF THE PIE FOR SOCIAL SECTORS

We may claim Bangladesh has achieved a lot in the last 10 years or so in terms of economic development. The continuous clocking of GDP growth of 6 percent and above may be a point, or the stable macroeconomic outlook or the gradual increase in per capita income to $1600 that makes it possible for us to qualify to be called a middle income country. These are the dividends of the grueling reforms initiated since the 1990s.

But somehow the burners seem to have died down and reforms stagnated and even reversed in some cases such as the financial sector. To survive as a middle income country, it needs continuous efficiency enhancing steps. Unfortunately Bangladesh has yet to get the new rules in place and this is reflected in the World Bank's recent report of Doing Business where Bangladesh still ranks low in the rank at 176th position out of 190 countries. True, it has improved two notches up from last year, but in the current global architecture such minor improvement does not make any difference.

This hemorrhaging of money has a vicious effect -- as project costs go up the government has to take more and more loans. This leads to bigger and bigger loan repayment obligation as is happening today. This in turn means less and less of the pie available to foot the bills for the preciously necessary social sectors.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments