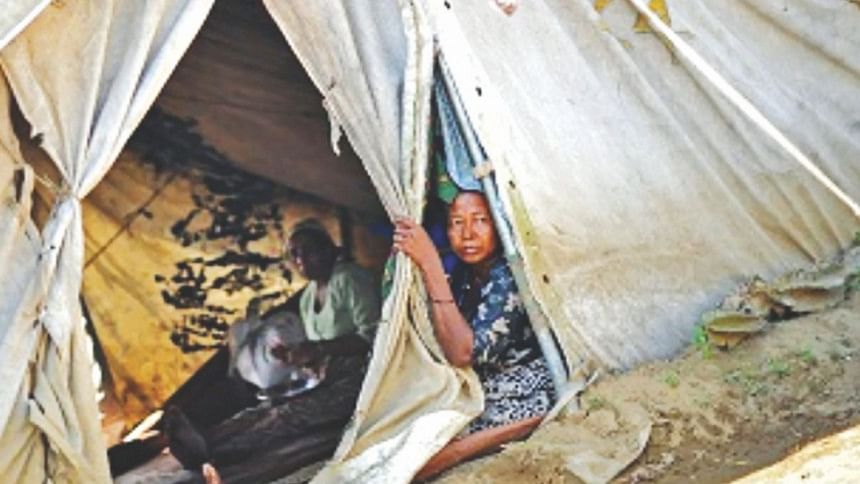

Camp or prison?

They are like prisons. Yet, the Myanmar government calls them camps. In those camps in Sittwe, the capital of Rakhine, one lakh Rohingyas have been languishing for almost six years.

The entire area is fenced off and the entrances are guarded by security forces. The inhabitants are forbidden to travel outside the squalid camps in an apartheid-like condition.

These so-called camps have become prisons for the Rohingyas who were confined there by the Myanmar government for the sake of their “safety”.

The Rohingyas suffer from chronic malnutrition and receive minimal medical care. They are not allowed to return to their homes from where they were ousted in the face of sectarian violence in June, 2012.

They don't even have any hope for going back. Nobody knows what happened to their homes and properties. The Rohingyas have become refugees in their own country.

The headline of a Time magazine report published four years ago perfectly described the situation in the camps: "These Aren't Refugee Camps, They're Concentration Camps, and People Are Dying in Them."

The whole world was more or less aware of the inhuman conditions of the Rohingyas, who are mentioned as Internally Displaced Persons (IDPs) in Myanmar's official records. They, however, lost the global attention following the latest wave of violence against the Rohingyas living in Rakhine state.

More than seven lakh Rohingyas crossed the border into Bangladesh after Myanmar army had launched a violent crackdown on them in August 25 last year. These people are also called IDPs.

Many of their houses and villages were burnt and bulldozed by the security forces. The Myanmar government has been constructing new camps. Many Rohingyas, once repatriated, will be kept in those camps as they have lost their homes.

However, the inhuman condition of those in the Sittwe camps seems to have terrorised the Rohingyas who have taken shelter in the camps in Cox's Bazar.

Therefore, they want the visiting delegation of the United Nations Security Council (UNSC) to put pressure on Myanmar so that it shuts down all the camps in Sittwe and does not build new ones for confining more Rohingyas after repatriation.

The closure of the camps is one the 13-point demands the Rohingyas are set to put forward to the UNSC team as it visits the camps in Cox's Bazar's Ukhia today.

The Daily Star correspondents, reporting from the upazila, have obtained a copy of the paper having the demands written on it.

The Rohingyas also want the UNSC to take measures for sending peacekeepers to Rakhine so that they can keep the refugees safe following their repatriation.

The hope for returning to home flickered in the minds of the Rohingyas languishing in the Sittwe camps after Kofi Annan-led Rakhine Advisory Commission had recommended closing the IDP camps and allowing freedom of movement there.

But a day after the former UN secretary general submitted its report to the Myanmar government, the security forces there launched the crackdown in August.

One lakh Rohingyas languishing in the camps again became a forgotten chapter. They will have to stay in those camps for an indefinite period. The Rohingyas who crossed over into Bangladesh are in the focus now.

This time around, Myanmar is building camps in Hla Po Khaung in northern Rakhine to temporarily accommodate 30,000 Rohingyas after their repatriation from Bangladesh, according to a report by state-run newspaper Global New Light of Myanmar.

Aung Tun Thet, chief coordinator of Myanmar's Union Enterprises for Humanitarian Assistance, Resettlement and Development, told Reuters in January that the camp in Hla Po Khaung would be a “transition place” for Rohingya refugees before they are repatriated to their “place of origin” or the nearest settlement to their place of origin.

But the Rohingyas, sheltered in Bangladesh cannot keep faith in the assurance from the Myanmar government. The tale of those rotting in the camps in Sittwe says it is indeed difficult to have faith in that.

The Rohingyas in Bangladesh fear they may end up having the same fate.

THE SITTWE CAMPS

On numerous occasions, the international media and human rights organisations have highlighted the inhuman living conditions in the Sittwe camps.

About the situation there, Time magazine on March 13, last year in a report said most days in the camps are far less joyous. The frequency of illness is hardly surprising; medical care is scarce and sanitary conditions are abysmal. Unclothed kids play in a stream of dirty water close to the camp's latrines, human waste scattered on the ground nearby.

Fortify Rights, a rights organisation based in Southeast Asia, in its report in 2014 said the Myanmar government has obligations under international laws to ensure that all displaced Rohingyas have liberty of movement to improve their livelihoods. But the government has failed to meet these obligations by restricting the freedom of movement of displaced Rohingyas.

It said the UN and several embassies in Myanmar have described the humanitarian conditions endured by the internally displaced Rohingyas as among the world's worst and pronounced the situation as “dire.”

The situation in those camps keeps worsening. A Sittwe Camp Profiling Report released in June 2017 said those temporary shelters became increasingly congested and the condition of the shelters deteriorated significantly since the camps were established.

Funded by the European Civil Protection and Humanitarian Aid Operations (ECHO) and UNHCR, the report said three potential solutions to internal displacement are to return to the place of origin, to integrate into the local areas where people initially sought refuge, or to resettle in another location.

The Myanmar government, however, all along remains nonchalant.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments