Dangerously exposed

The recent hacking of the Bangladesh Bank system to steal at least $100 million reveals the vulnerability of the central bank's IT infrastructure, weak operational architecture and probable insider link.

The heist also puts to question what kind of network architecture and firewall it has in place. Everybody is talking about malware injection into the BB system but nobody is asking how the malware could enter the supposed-to-be most robust and secure system of a central bank in the first place.

Suggestions were made that the problem might lie with the SWIFT or the Society for Worldwide Interbank Financial Telecommunication that provides a very secure financial encrypted messaging system through which orders are placed across the globe. The Federal Reserve (Fed) was blamed for allowing the transactions.

However, the Fed has categorically said its system was not compromised. And SWIFT issued a statement on Friday which also indicates that it is not its system rather that of the Bangladesh Bank that is in question.

The SWIFT statement read: “SWIFT and the central bank of Bangladesh are working together to resolve an internal operational issue at the central bank. SWIFT's core messaging services were not impacted by the issue and continued to work as normal.”

So if the Fed was not compromised and neither was SWIFT, what may have gone wrong? Let's analyse the issue.

First we should know about SWIFT. It is a cooperative society under Belgium law owned by its member financial institutions that provide encrypted messaging service to facilitate global financial orders.

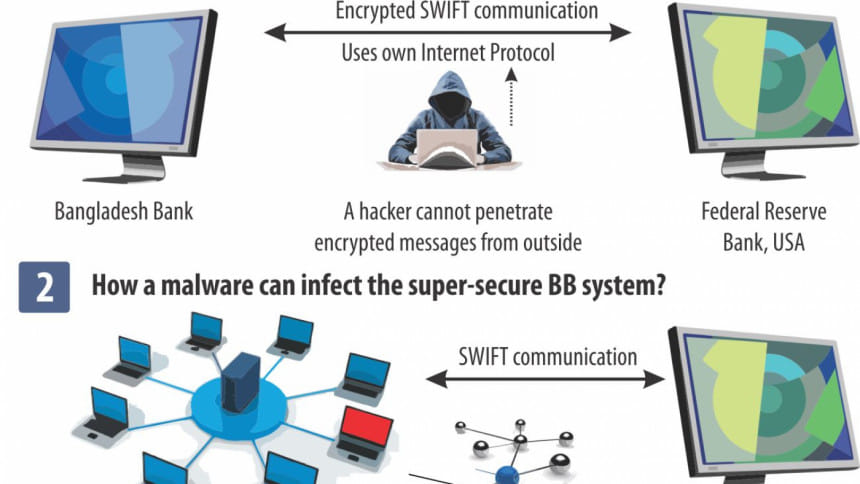

Its communication has so far proven hack-proof because these are end-to-end encrypted and sent through its own IP network infrastructure known as SwiftNet. As such there is no chance for outsiders to intercept messages using any malware or Man-in-the-Middle (MitM) attack.

MitM is an attack where the attacker secretly relays and alters the communication between two parties who believe they are directly communicating with each other, in this case, between Bangladesh Bank and the Fed.

But since SWIFT has its own protocol network and software which relies on high encryption, it is highly unlikely that an MitM attack breached the security.

So then what may happen?

The answer may lie with the end-point malpractice or abuse, in this case at the Bangladesh Bank.

The BB uses the BTCL backbone for all electronic communication. The mainframe server of Bangladesh Bank should have been connected with the BTCL with a secure intranet communication, which should be isolated from any sort of internet communication to avoid outside injection of malware. If this was the practice, then the SWIFT communication should have been completely secure as the mainframe server has no possibility of being infected.

So the Bangladesh Bank should clarify if this network architecture it was following. And if this was being followed, the only way the SWIFT communication could have been exploited is by physical excess to the mainframe server. This would clearly be a case of insider job.

But if the BB had not used intranet-based secure communication, then a different scenario comes out. In that case, it had used internet to connect with the BTCL server with an exposed endpoint to internet. Hackers then can use that endpoint to get inside the network of the central bank.

But suppose the BB had used intranet with the BTCL, still it could have an exposed endpoint if its mainframe server was connected with other computers or even a single computer on the premises which had internet access. In that case it would leave the system accessible to outsiders via that computer with internet access.

If this was the case, we are not dealing with an insider job but with a very sloppy IT architecture for which relevant people must be held accountable and, if proven, punished.

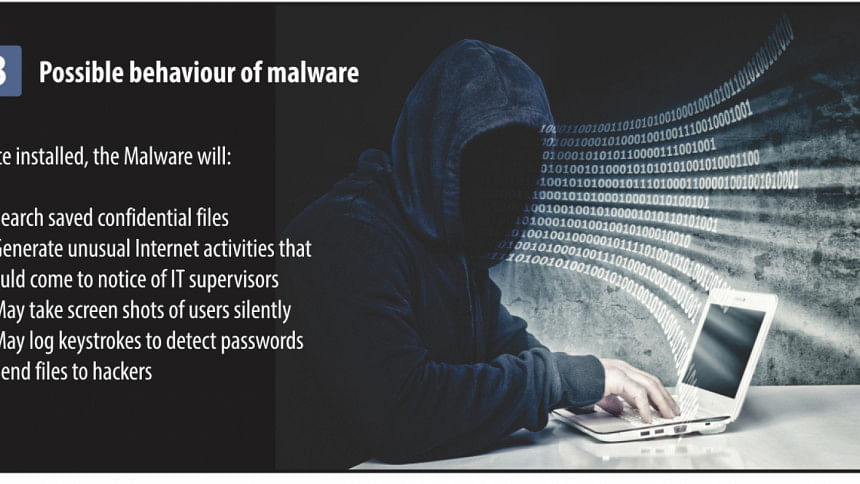

If malwares were injected, there would certainly be symptomatic signals. There would have been a sudden wave of outgoing data requests or some other symptoms that would have immediately raised alarm in the fire fighting section. What did the IT department do? Do they not have any network monitoring tool to detect suspicious network activities during weekend or off-office hours? Or was the system too weak that nobody checked the doubtful operations?

There are many more questions. For example, we still do not know when the BB had first acted after the fund was transferred. Even in personal banking, an unauthorised transfer can be checked by taking immediate steps. So then why could the BB not stop the fund disbursement? Every fund transfer is notified through various platforms. In this case, is it enough of an explanation that the BB could not know about the fund transfer immediately because of Friday and Saturday being holidays and also days of the heist? This only reveals the sheer callousness of the central bank in handling its IT operations.

Where was the BB's two-way security policy? Even in simple day-to-day emailing, a user may enable a system that would generate a code on the user's mobile every time he wants to log in and he has to put that code to access his mail. If a simple email system can have such security measures then why should the BB not have a better or at least the same kind of security layer? Or is it that it did have the security layer but it was compromised because of an insider link?

With all the security measures mentioned here, the BB server could still be hacked if someone injects a malware physically using a USB drive or a CD Rom. Still, that makes it an insider job.

There are numerous other questions that remain unanswered. How the BB reacted to the whole thing also raises a lot of questions. It kept the thing under the wrap for about a month and did not even inform the finance ministry. We came to know about the incident only after the whole thing came out in the Philippines newspaper. Would we have ever known if the Manila-based newspaper did not publish the story? How do we know there were not more transfers we do not know about because these were not reported by newspapers?

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments