BB fund: Fed could but failed to stop cyber heist

The way the Federal Reserve Bank of New York acted in handling the fund transfer requests made by the hackers from Bangladesh Bank's accounts has raised questions about the Fed doing proper due diligence before executing the fund transfers and whether its fund transfer request authentication process falls short of standards.

It now seems, had the Fed been cautious about financial transactions, the funds could easily be stopped from being transferred to banks in the Philippines and Sri Lanka, and from there to the pockets of the hackers.

About a month after the heist in which hackers used malwares to make illegal requests to the Fed and transferred $101 million from Bangladesh Bank's account, questions are also being raised about how secured is SWIFT, the messaging system through which fund transfer requests are made. Some believe there is enough evidence to suggest that the SWIFT system was also compromised.

The crucial five days

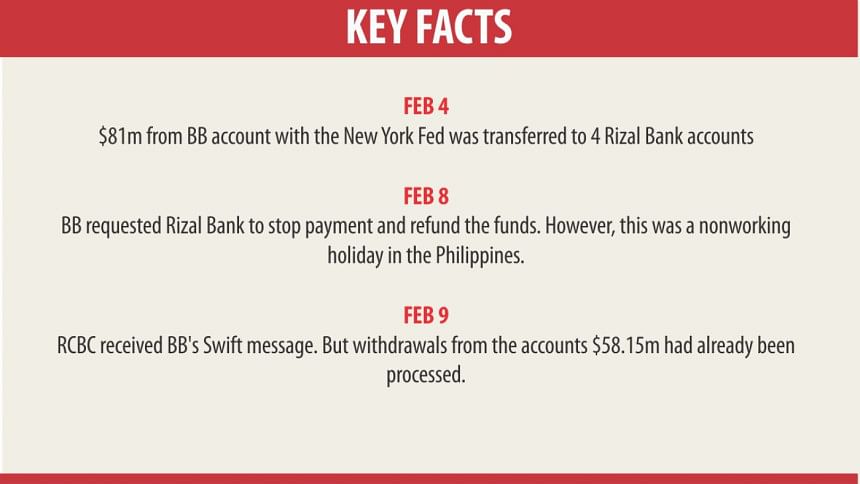

The hackers hacked into the system on February 4 and placed payment orders which were finally paid on February 9 into the accounts of the hackers' beneficiaries. A quick view on what happened during those five days clearly shows the Fed had not acted responsibly to stop the fraudulent transfer of the money.

The hackers first made the payment request in the guise of Bangladesh Bank on February 4. The Fed thought it was rather unusual for a central bank to order payment to several private accounts. So it sent a query to Bangladesh Bank at 17.55 New York time on that very day.

But strangely, even before making the query, it had cleared and executed five of the fake orders. This clearly shows although the Fed had raised red flags against suspicious orders, it failed to act accordingly and executed the payment instructions.

After making the payments, it made queries about 12 other payment orders. The hackers had disabled the printer attached to the system that would have shown the queries in hard copy printouts.

THE QUERIES AND THE LETDOWNS

In one of its queries, the Fed mentioned the payment instructions known in banking parlance as MT103 and then wanted more information on the official purpose of these transactions and the identity of the beneficiaries – Ralph C Picache and Enrico T Vazquez – and their connection to official business and the purpose of the payment.

This, the Fed said, was necessary as it fulfilled its risk management and due diligence requirements.

In the following queries about the payment orders to Sri Lanka and Manila, the Fed sounded more alarmed, probably because of the number of the payment instructions it was receiving and also because it did not receive any reply from Bangladesh Bank.

It sought a long list of information including the full details of the beneficiary. For individuals, it wanted to know their occupation and connection to the originating party, the Bangladesh Bank in this instance.

The hackers sent $20 million to a Sri Lankan account in the name of ShalikaFundation (they had actually misspelt foundation). Fed was suspicious about it and wrote “for beneficiary 'ShalikaFundation' please provide nature of business and physical address.” It also wanted to know the website references for all beneficiaries.

The Fed seemed to be cautious particularly about three individual beneficiaries – Jessie Christopher M Lagrosas, Enrico T Vazqez and Alfred S Vergara. It queried about the professional relationship, if any, between these three individuals.

It also wanted to know why the payments were being made by providing “the full details of the underlying goods and services covered by these payments.”

And last of all and probably the most important question it made was, why the payments that represented payment of institutional loans and interest were being made to these individual beneficiaries.

So it is now clear from the Fed's queries that it had suspected something seriously wrong in the whole thing and yet it fell short of stopping the payments immediately by taking initiative until clarification came from the Bangladesh Bank.

ANOTHER CRUCIAL DAY GOES BY WITHOUT ACTION

The next day (February 5, Friday), the Fed sent more queries relating to the paid instructions and another 30 between 16.09 and 16.43 NY time. None of them were seen here because the printer was disabled by the cyber criminals.

The strangest thing is even though the Fed had suspected wrongs in the orders as evident by its numerous queries, it did not stop payment of the funds from its system. Nor did it take any step to ask the banks in Sri Lanka and the Philippines to stop payment to the private beneficiaries, including a casino owner in Manila.

And the fact is the funds were not released to the hackers' until February 9, five days after it raised red flags and started sending out queries.

On the 5th of February, the Fed had finally said it was unable to carry out the fake orders. Again the most important questions are: 1.Why did it not refuse payment as soon as it received the suspicious orders; and 2. Why it did not stop or recall the payments as it obviously had sensed something wrong?

Moreover, it also shows the Fed, being such a custodian of global reserves, did not have a proper alert system in place, otherwise it would have suspected foul play in the first place and then acted accordingly.

This point gleans from the fact that Bangladesh Bank had never made any fund transfer request upwards of $26 million and never to any individuals. So the moment such huge transfer orders to the tune of $81 million were made in favour of individuals, Fed should have raised red flags and protected its customer's funds.

The other curious thing is although the Fed had sent so many queries on suspicion and did not get a single feedback, it should have immediately called or contacted Bangladesh Bank by alternative means which it did not do. No response from Bangladesh on their queries should have made it clear that something out of the ordinary had happened.

SHOCK AND FLURRY AT BANGLADESH BANK

BB officials had found the SWIFT printer out of operation on Friday. They tried to fix the issue but could not solve it. When Bangladesh Bank officials started work on Saturday, February 6 and found their system still not working and the printer dysfunctional, they immediately sensed something was not right. The BB sent its first message at 1.31pm on February 6 asking the Fed to stop payment. Then they faxed the same mail to the Fed.

The BB officials sent two more messages at 4.44pm and 6.03pm. Then they found out the phone number of the Fed from its website and called the number. Nobody picked up in New York as it was Saturday and so its weekend had become a barrier. Strangely for the Fed that manages funds from countries all over the world, it did not feel necessary to keep a skeleton staff to respond to mails and answer calls in this type of situation, particularly, since it had already raised serious queries with BB and should have been expecting feedback.

Only if it had this system in place, the payment of funds could still be stopped since the hackers received the money from the banks on February 9.

“I can't imagine that Fed keeps its office shut off on weekends. Even if it does, they should have expected that Bangladesh Bank may contact them because of the seriousness of the issue and kept its eyes and ears open to any communication from Bangladesh,” said a central banker.

New York opened on February 8 and the Fed found the BB's mails and acknowledged them.

Fortunately banks were closed on that day in the Philippines on account of the Chinese New Year. This is the reason that Rizal Banking Corporation could not release the funds to the hackers' designated account.

However the last opportunity to stop the heist was lost as the Fed did not order the Philippines banks to stop the payments until after the money had left the accounts.

Eventually the next day, February 9, Rizal Bank released the money to the hackers.

BB'S LAWYER BLAMES FED AND SWIFT SQUARELY

Queen's Counsel Ajmalul Hossain, who now handles the case for Bangladesh Bank, has a very precise point to make about the Fed's role.

“As far as the Fed is concerned the main allegation that we, on behalf of Bangladesh Bank, have is that it paid out money from our account on the instructions of a third party,” Hossain said. “That is now very clearly established.”

“It is very clear to me, from the documents that I have seen, that at the very least the Fed was negligent in not taking appropriate action in respect of the fraudulent payment instructions that were received,” he told The Daily Star.

The payment instructions received were clearly inconsistent with all the previous genuine instructions that were given by BB.

“None of them were to individuals. That is one factor,” he pointed out. That was precisely one of the queries raised by the Fed with the central bank.

“The Fed requested information from Bangladesh Bank after they had actually made the payments. If the Fed made a query about some doubtful transactions we think it was incumbent upon the Fed to at least send a message to the beneficiaries' bank to hold those payments and not make payments on the instructions of the beneficiaries.”

That instruction should have gone out immediately when there was a query. Obviously, it raised a red flag; this is in the public domain. No one disputes that.

“Why didn't the Fed act properly as they should have, as bankers, to ensure the money was not going to third parties fraudulently?” Hossain asked.

Andrea Priest, vice president for media relations at the New York Fed, declined to comment yesterday.

Earlier in a statement, the Fed denied that its payment systems were breached.

“There is no evidence of any attempt to penetrate Federal Reserve systems in connection with the payments in question, and there is no evidence that any Fed systems were compromised,” Priest said on March 16.

“The payment instructions in question were fully authenticated by the SWIFT messaging system in accordance with standard authentication protocols. The Fed has been working with the central bank since the incident occurred, and will continue to provide assistance as appropriate.”

SWIFT'S QUESTIONABLE ROLE

Bangladesh Bank has identified a number of issues in SWIFT implementation that may indicate weakness in SWIFT operations.

When SWIFT installed the Real-time gross settlement systems (RTGS), a specialist funds transfer systems where transfer of money or securities takes place, it did not supply Operation Guide and necessary safety and security instructions to be followed by the BB's SWIFT operation team.

Here, the BB team also seemed to be obliviously of not getting such manual.

After RTGS implementation, SWIFT servers have been interfaced with the whole BB network and SWIFT system became interlinked. SWIFT implementation team did not inform the BB teams about any security hole.

Also intriguing is the SWIFT messages requesting payment of funds were deleted from BB SWIFT Alliance Access Server.

“We also think that the online platform that was used and that was in use was compromised. The online platform contained not only the SWIFT's platform but also the Fed's platform and the BB platform.

“They were integrated. The integration was done by SWIFT itself. SWIFT obviously guarantees that their system is impregnable, but their system was clearly compromised. The investigation by SWIFT has not yet been completed, and we know for a fact there were a long time and a long gap between the requests by the BB for copies of the fake instructions and the receipts of the copies of those instructions.”

“The inference we are drawing from the delay is that the malware that was used to access the payments deleted information on SWIFT server. And that is the reason why we think that the SWIFT server and the Fed were not as safe, metaphorically speaking, as the Bank of England,” Hossain added.

The extent of the hacking unfolded very slowly. First it was believed that the hackers placed five requests to transfer $101 million, but now as the Fed and SWIFT have come up with the full list of requests weeks later, it seems that the hackers actually made 70 requests to transfer $1.94 billion. Banking and IT experts question why Fed and SWIFT should take such a long time to exactly determine the number of requests.

Officials of SWIFT did not immediately respond to e-mail for comment.

In a statement earlier, SWIFT said: “We reiterate that the SWIFT network itself was not breached. There is a full investigation underway, on what appears to be a specific and targeted attack on the victim's local systems.”

Gottfried Leibbrandt, chief executive officer of SWIFT, wrote a letter to its clients in Bangladesh on March 20.

In the letter, Leibbrandt insisted that SWIFT's core messaging services were not impacted by the issue and those continue to work normally. “There is no indication that our network has been compromised,” he said.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments