A friend in need

He was here only for his job. When the Liberation War broke out, he could have slipped out of the country to safety.

But William AS Ouderland, who came to East Pakistan in the 70s as the CEO of Bata Shoe Company, chose to join the fight for the independence of Bangladesh. It was because of the "love and affection" he "felt for the Bangalee people", as he once wrote in a letter to a friend.

This was not the first time war came to the Dutch-Australian man's life. Born in Amsterdam during the First World War in 1917, he participated in the resistance against the occupying Nazis in WWII.

"Therefore, when events of March 1971 started with Tanks and Pakistani forces rolling in to Dhaka, I was re-living my experience of my younger days in Europe," wrote Ouderland to his friend Anwar Faridi more than two decades later after 1971 war.

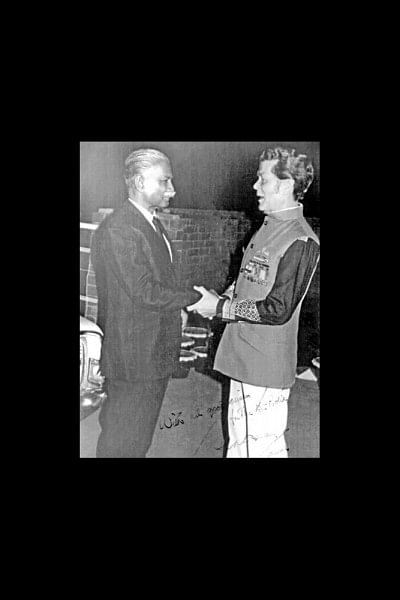

Ouderland, also a former sergeant of Royal Signal Corps of the Netherlands, is the only foreigner who was honoured with the fourth highest gallantry award, Bir Protik, for his outstanding role in the Liberation War of Bangladesh.

When the Pakistan army launched the infamous "Operation Searchlight" on March 25, 1971, Ouderland, at the first chance, took pictures of different parts of the city, including Dhaka University, to record the death and destruction and passed those on to the international media.

He had got a "curfew pass" from the military that allowed him to move around the city during the restricted hours. Besides, he used to fly the Australian flag on his Ford Fairlane car for added protection.

He had access to the top brass of the Pakistan army in Dhaka, including Lt Gen AAK Niazi, Lt Gen Tikka Khan and Maj Gen Rao Farman Ali, the officers intimately involved in the military operation and genocide.

Col (retd) Newaz of Baluch Regiment, who was the personnel and public relations manager of Bata in Lahore, introduced Ouderland to Niazi and Tikka during one of his visits to Dhaka.

Making good use of his unhindered access to the cantonment and residences of Pakistani high officials, Ouderland began collecting secret information and passing it on to Col (retd) Osmani, commander-in-chief of Mukti Bahini, and other senior Bangladeshi officials.

Ouderland grew up in a poor family in the Netherlands. Shoe shining was his family occupation.

He was conscripted into the national service in 1936 shortly after he got a job in Bata. During the Second World War, he was called up to serve as a sergeant in the Royal Signal Corps of the Netherlands.

Ouderland was captured by the Nazis and interned in a POW [prisoner of war] camp. But he managed to escape after a short time and joined the Dutch underground resistance movement as a spy as well as a guerrilla to drive out the Nazis from Holland.

"As I spoke fluent German and several Dutch dialects, I befriended the Germen high command and was thus able to help the Dutch underground movement," wrote Ouderland in a letter.

This experience would come in handy when he joined the fight against another occupation force far from home.

He formed a secret group with a handful of Bata staff to secretly work with the freedom fighters. His comrades included Bata's personal manager AKM Abdul Hai, physician Dr Hafizul Islam Bhuiyan and officials Abdul Maleque and Humayun Kabir Khan.

The Australian High Commission knew about his mission but did not stop him.

The Daily Star could contact Abdul Hai, a close confidant to Ouderland.

"Ouderland was not a Bangalee but he loved the land just like any other freedom fighter," said Hai. Tears welled up in the 81-year-old's eyes, reminiscing about his foreign colleague.

At the early stage of the war, Hai said, he moved to the Bata factory area in Tongi in the outskirts of the city with his family on Ouderland's advice.

The Pakistan Army took over the Telephone Industries Corporation (TIC), adjacent to the Bata factory soon. The danger of living next to a military camp prompted Ouderland to make two bunkers for his staff on the grounds of the Bata factory.

The bunkers would save the lives of more than 50 people later in December when the Indian air force attacked the Pakistani camps next door, Hai recalled.

About Ouderland's intelligence gathering, he said, "Ouderland would praise the Pakistanis and criticised the Bangalees to gain the army's confidence. The officials freely shared their plans with him.

"We used to send the gathered intelligence to a den at Zinzira in Dhaka to be forwarded to Osmani."

Ouderland sent his wife and daughter away to Australia and threw open the doors to his residence to the freedom fighters.

He hid weapons in the rooftop water tank, regularly sent shoes, blankets and medicine to freedom fighters. He had a pistol that he gave to Joynul, a Mukti Bahini member of sector 2.

Ouderland engaged Bata's Dr Hafizul Islam for treatment of injured fighters.

Despite his contributions, Ouderland did not get the citizenship of Bangladesh though he applied for this after the independence, said Abdul Hai.

He left Bangladesh in 1978 as his health deteriorated.

Later, some Bangladeshis in Australia started a campaign for granting citizenship to this friend of Bangladesh. But before their efforts could get results, Ouderland passed away in Perth in Australia on May 18, 2001.

Bangladesh invited him twice to honour him in 1992 and 1998. He could not make it because of poor health. But he donated Tk 10,000, the award money he got in 1998, to the Bangladesh Freedom Fighters Welfare Trust.

The Bangladeshi community in Australia has formed Ouderland Memorial Committee. A library has been named Ouderland Memorial Library at the Bangladesh High Commission in Canberra.

Bangladeshis and the high commission paid tribute to Ouderland on May 24, 2001 at his funeral in Perth. They sang the national anthem of Bangladesh before his coffin draped with the red and green flag of Bangladesh, said Kamrul Ahsan Khan, convener of the memorial committee.

The road in front of the Australian High Commission in Dhaka has been named after William Ouderland, a friend who loved the freedom loving people of this country.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments