Intent to deceive

Myanmar is living up to the global suspicion about its real intention behind signing the deal for repatriation of more than seven lakh Rohingya refugees. The intention, as suspected by experts and global rights bodies, was all but taking back the Rohingyas.

International relations analysts had warned, well before the signing of the Rohingya repatriation deal in November last year, that Myanmar's hasty move for a bilateral agreement was a trap for Bangladesh and an eyewash to appease the international community.

The global community, which vehemently criticised Myanmar's brutal military operation that sent the minority people fleeing for their lives and pouring into Bangladesh since August last year, also expressed doubts over the success of the deal.

And four months into the agreement, their collective suspicion has started turning out to be true.

The voice of the international community seems to have weakened by now, but that of Myanmar remains strong and it holds Bangladesh responsible for the “delay in repatriation”.

The country has not allowed rights investigators and independent journalists in Rakhine State where its forces carried out wide-scale atrocities, termed by the UN a textbook case of ethnic cleansing.

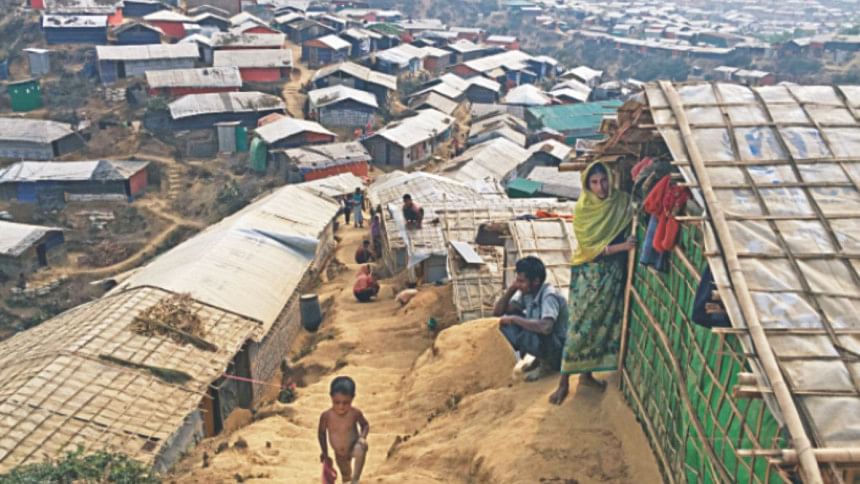

Bangladesh, however, is doing whatever is necessary for the repatriation alongside bearing the huge brunt of the fastest growing refugee crisis of recent times and providing humanitarian assistance to over a million Rohingyas in Cox's Bazar.

“Bangladesh signed the deal in good faith but Myanmar with mala fide. If things remain the same, there is a high possibility that the Rohingya crisis is going to be a longstanding one,” said Dr Mizanur Rahman, law professor at Dhaka University.

Already, wages of day labour in Cox's Bazar have gone down, while food prices went up and the forest in large parts of the tourist district has been cleared.

The situation could aggravate, said the DU professor, especially because the international community's resources and focus are distributed among many other refugee crises of the world, while the UN Security Council members are divided on the issue over their own national interests.

Mizanur Rahman, also a refugee law expert and former chairman of National Human Rights Commission, said Bangladesh has made a blunder by not incorporating the UN in the repatriation deal.

“Under the present conditions, it will be very difficult for Bangladesh to repatriate the Rohingyas,” he told The Daily Star on March 19.

This fear rises as the Myanmar announced that only some 600 from the list of 8,032 Rohingyas that was handed over to them on February 16 were eligible for return.

On March 14, U Myint Thu, permanent secretary of Myanmar's foreign ministry, at a press conference in Naypyidaw said the verification forms received from the Bangladesh side were not the ones agreed by both sides.

“Those forms did not provide basic information, including former place of residence, voluntariness of return, signature and finger prints of each member of the household, clear photograph and other supporting documents,” he said.

Bangladesh's Refugee Relief and Repatriation Commissioner Abul Kalam questions how the 600 Rohingyas were verified if the verification forms were not the ones agreed by both the countries.

Talking to The Daily Star on March 16, all the forms were filled up in similar fashion, and so the allegation of Myanmar that the forms lacked certain basic information was not right.

As per the deal, the repatriation was supposed to begin on January 23. But during a meeting on January 16, Naypyidaw demanded a family-wise list of Rohingyas, and Dhaka, upon agreeing to that, has been working accordingly.

Yet, the Myanmar ministers and officials told international media on January 22 that Bangladesh was responsible for “delaying” the repatriation.

Experts said the nitty-gritty of registration and list can be solved through discussions, but Myanmar's attitude of blaming Bangladesh reflects its bad intention, especially when it has been destroying all evidence of genocide in Rakhine.

Independent researcher Asif Munier said as per the repatriation agreement, the Rohingyas will have to prove their residency in Rakhine by presenting papers or by providing information about their village, school, mosques, etc.

“Most Rohingyas have lost their paper IDs as their homes were burned. Now, as their villages are being bulldozed and other installations being erected, it will be nearly impossible for the Rohingyas to prove their residence,” he said.

Munier said determining voluntariness of the Rohingyas for their return is a vital part, but it must be done by a third party, for example, the UN High Commissioner for the Refugees (UNHCR).

Myanmar itself refused to engage the UNHCR in the repatriation deal and now it is raising the issue of voluntariness. This is nothing but a joke, he noted.

CONDITIONS FOR RETURN

Myanmar said it was building camps as temporary shelters for the Rohingyas, but the refugees in Cox's Bazar demanded a safe zone under the UN supervision to ensure their safety for return to Myanmar.

UNHCR head Filippo Grandi recently said refugees must be able to return to a place of their choice, including the location where they previously resided, suggesting avoidance of temporary arrangements.

He observed that temporary camps have a tendency to persist for considerably longer than envisaged, and to take on a permanent character.

However, the Myanmar authorities have not changed its mind.

They are now bulldozing Rohingya villages, establishing military installations and bringing ethnic Rakhine people from other parts of Myanmar to the places mostly "cleared" of its Rohingya residents in Rakhine State, Amnesty International said last week.

Under such circumstances, Rohingyas are still crossing over to Bangladesh amid food shortage and slow persecution, it said.

“Myanmar is making a mockery out of the repatriation deal with Bangladesh,” said regional security analyst Brig Gen (retd) M Shakhawat Hossain.

In fact, Myanmar has been systematically persecuting the Rohingyas since 1962 and hundreds of thousands of them fled to Bangladesh since 1978.

Those who returned had to flee again. Before the latest crisis, there were some 300,000 Rohingyas in Bangladesh.

After the deadliest violence since August last year, Shakhawat Hossain said, Rohingyas are more scared than ever to go back as they fear more persecution on their return under present circumstances.

“Rohingyas would not go back to the place where their homes were destroyed and their relatives were killed in thousands and women raped,” he said.

REVIEW DEAL, ENGAGE UN

Experts have suggested that Bangladesh should review the bilateral deal with Myanmar to incorporate the UNHCR in the process.

“The Rohingya crisis is in no way a bilateral issue. It's an international issue and has to be handled by the UN. International actors must play a vital role here,” said Asif Munier.

Myanmar is now implementing its blueprint of cleansing the Rohingyas, and Bangladesh cannot be part of it. “Can Bangladesh avoid responsibility if the Rohingya face further persecution on return to Myanmar?” he questioned.

He recommended forming an international body, which should also include representatives of the Rohingya, to monitor the situation in Rakhine and the repatriation process to make it safe and sustainable.

Prof Mizanur Rahman said Bangladesh should engage the regional actors -- both bilaterally and regionally -- for a permanent solution to the crisis that has wide regional security implications.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments