Little progress in nutrition status

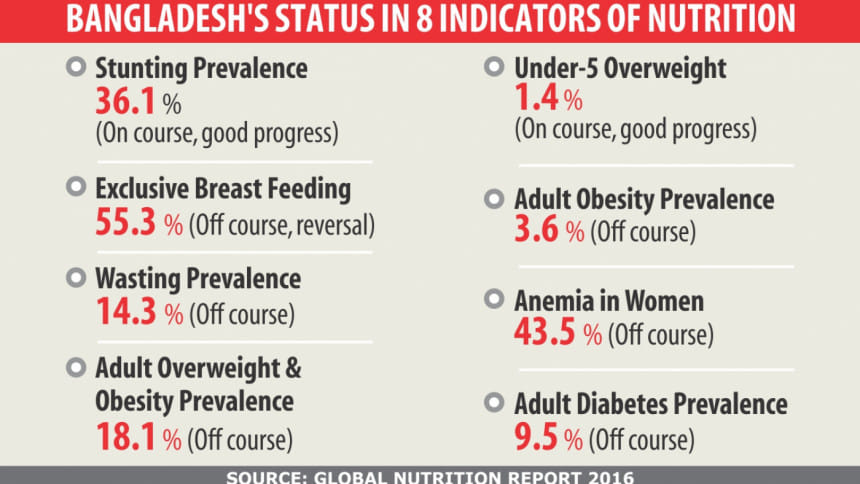

Bangladesh has made good progress in two of the eight nutrition indicators -- stunting and child overweight -- but is slipping back in exclusive breast feeding while doing badly in the rest five indicators, according to this year's Global Nutrition Report (GNR).

The five indicators are: wasting (low weight for height), anemia in women, adult overweight and obesity, adult obesity and adult diabetes.

The 2016 GNR, released on June 14 in Washington DC, provides an independent and annual review of the state of the world's nutrition. The report, now in its third year, focuses on the progress made towards recent nutrition-related global commitments and identifies opportunities for action to end malnutrition in all its forms by 2030.

An International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI)-led team of experts prepares the report. The World Health Organisation (WHO) is a partner in the GNR publication.

Though the rate of stunting -- low height for age -- is still high at 36.1 percent in Bangladesh, it is now dropping faster than in the past. The rate was 41 percent in 2011 and 51 percent in 2004. Its current stunting rate, although higher than some of its South Asian neighbours, stands better than that of Nepal (37.4%), India (38.7%), Afghanistan (40.9%) and Pakistan (45%).

The rate is 14.7 percent in Sri Lanka, 20.3 percent in the Maldives and 33.6 percent in Bhutan.

Bangladesh is marked “on course” in this particular nutrition indicator as it has come a long way over the last one decade.

The GNR referred to a research carried out in Bangladesh by the IFPRI and the World Food Programme (WFP) showing how stunting could be reduced far more quickly had nutrition education been tagged with social safety net programmes (SSNPs).

This nutrition education is technically called behaviour change communication (BCC).

Reached over the phone yesterday, IFPRI Chief of Party in Bangladesh Dr Akhter Ahmed said their study in 500 villages during 2012-14 showed that malnutrition and childhood stunting can be brought down three times faster by incorporating nutrition BCC in different SSNPs.

An IFPRI study has found that mere transfer of food or cash under the SSNPs would not make much difference in terms of improving people's nutrition level unless these programmes were tagged with nutrition BCC.

This means people should be advised as to what food items should be on their menu and how the food should be consumed.

While visiting Dhaka a few months ago, GNR lead author Lawrence Haddad told The Daily Star that stunting rate was coming down fast in Bangladesh but the pace could be even faster provided the country invested more for nutrition.

"If Ghana can reduce stunting to 19 percent, Bangladesh can do it as well. President Lula [da Silva] left a legacy in the fight against stunting in Brazil. Bangladesh can fight malnutrition too," noted Haddad, also a Senior Research Fellow at the IFPRI.

In Bangladesh, wasting remains high at 14.3 percent, far above the global target of five percent.

According to this year's report, Bangladesh remains at the bottom end (117th) of a 130-country ranking. Except for India (15.1%) and Sri Lanka (21.4%), five of its neighbours -- Bhutan (5.9%), Afghanistan (9.5%), the Maldives (10.2%), Pakistan (10.5%) and Nepal (11.3%) -- are faring well.

The report reveals 43.5 percent Bangladeshi women in their reproductive age are anemic. In terms of anemia, Bangladesh ranked 158th among 185 countries and 5th among the eight South Asian countries. Women in Sri Lanka, Afghanistan, Nepal and the Maldives are less anemic than their Bangladeshi counterparts. Scenarios in India, Bhutan and Pakistan are worse.

In the indicator of exclusive breast feed (EBB), the report says Bangladesh is slipping back from the progress it made. Its EEB rate is a little over 55 percent now which was 60 percent a few years back. A GNR author attributed it to the spread of urbanisation, the increase in women's participation in formal workforce, and lack of facilities at workplace for lactating mothers.

Asked, Prof Nazma Shaheen who teaches nutrition and food science at Dhaka University contested the EBB rate, however. She said it showed lesser percentage now because of some adjustments made in the indicator's definition and criteria in recent years.

The Daily Star could not verify this with the GNR authors.

The 2016 GNR report estimates that malnutrition causes significant economic losses -- 11 percent of the GDP per year in Africa and Asia.

Similarly, in the US, for every obese person in a household, that household's healthcare bill increases by an equivalent of 8 percent of the annual income.

However, one of the key messages of the report is that this dire situation masks significant opportunities. The economic returns on investments preventing malnutrition are extremely high -- $16 for every $1 invested. The report illustrates numerous examples of countries, such as Brazil, Ghana, Peru and Vietnam, which have seized these opportunities and made rapid progress in tackling malnutrition.

Globally, the world is off-track to meet most nutrition targets by 2030, but the rate of progress varies significantly by country and indicator. Most countries and regions are on course to achieve targets on child stunting (except for Africa), wasting, and overweight.

Conversely, most countries are off course on targets on obesity, diabetes, and anemia in women. Indeed, obesity and overweight rates, currently at 1.9 billion people, are rising in almost every country and are now approaching the same scale of other forms of malnutrition.

At least 12 of the 17 Sustainable Development Goals are directly related to nutrition and nutrition-related indicators. This reflects nutrition's central role in achieving sustainable development, as well as its interrelationship with the majority of development sectors.

The report highlights that improvements in nutrition are necessary for achieving progress on global health, education, poverty, female empowerment and inequality.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments